by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2019

Section of The Marriage of Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh by Nicholas Chevalier; Credit – Royal Collection Trust

Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, later Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia were married on January 23, 1874, at the Winter Palace in St Petersburg, Russia. Alfred was the only one of Queen Victoria’s nine children not to marry in his home country.

Alfred’s Early Life

Alfred, on the left, with his elder brother Bertie, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII; Credit – Wikipedia

Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, was the second of the four sons and fourth of the nine children of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. He was born at Windsor Castle in Windsor, England on August 6, 1844. After being educated at home, along with his older brother The Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII), Alfred entered the Royal Navy at just 14 years old. Rising quickly through the ranks, by February 1866 he had been elevated to the rank of Captain, and the following year was given command of his own ship, HMS Galatea. Alfred went on to have a thirty-five-year career in the Royal Navy.

Along with his military career, Prince Alfred studied at the University of Edinburgh and the University of Bonn. With his future role as Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in mind, in 1865 Alfred purchased a palace in Coburg, just across the square from Schloss Ehrenburg, the official ducal residence. This palace, known as Palais Edinburg, would be his residence in Coburg until his accession 28 years later.

To learn more about Alfred, see Unofficial Royalty: Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Maria’s Early Life

Maria with her father and her brothers (Grand Duke Paul had not yet been born) – From left to right: Grand Duchess Maria, Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia with Grand Duke Sergei in his lap, Grand Duke Vladimir, Grand Duke Alexander (the future Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia), Grand Duke Alexis and Tsarevich Nicholas (who was the heir but predeceased his father); Credit – Wikipedia

Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia was born on October 17, 1853, at the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo, near St. Petersburg, Russia. She was the only surviving daughter of the two daughters and the sixth of the eight children of Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia and Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine. Maria was the sister of Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia, and the paternal aunt of Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia. She was raised in luxury and splendor in the large palaces and country estates owned by the Romanovs. Maria was the first Russian grand duchess to be raised by English nannies and to speak fluent English. Besides her native Russian and English, she was also fluent in German and French.

To learn more about Maria, see Unofficial Royalty: Maria Alexandrovna of Russia, Duchess of Edinburgh, Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

The Engagement

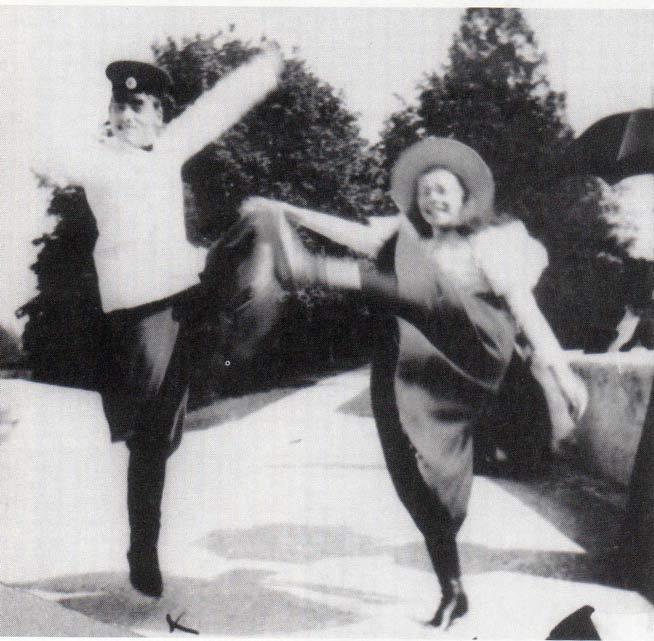

Alfred and Maria’s engagement photo, 1873; Credit – Wikipedia

Alfred and Maria first met in August 1868 in the Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine. Maria’s mother was born a Princess of Hesse and by Rhine and Maria and her family were visiting their Hesse and by Rhine relatives. At the same time, Alfred was visiting his sister Alice who had married Maria’s first cousin, the future Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine. Alfred was impressed with Maria and needed little encouragement from his pro-Russian sister Alice to consider Maria as a potential bride. However, Alfred’s Royal Navy commitments kept him away until 1871.

Alfred, along with the Prince and Princess of Wales, visited Hesse and by Rhine in 1871 as did Maria, along with her parents and her two elder brothers. Maria and Alfred spent much time together, walking, talking, and playing music together. Alfred made his feelings regarding Maria known to her father. Alexander II wrote to Victoria that he did not oppose a marriage between their children but that they would have to wait a year for a definitive decision because Maria was so young, and he was reluctant to ever part with his only daughter. Queen Victoria was also unsure about the marriage because of Maria’s Russian Orthodox religion. Both countries had negative feelings about the other country relating to when they were on opposites sides in the Crimean War (1853-1856). Negotiations dragged on and on, with no progress. In 1873, there an Anglo-Russian dispute over the Afghan border, and Queen Victoria’s government thought a marriage between the two countries might ease the tension.

In July 1873, Alfred and Maria, accompanied by her parents, met again in Hesse and by Rhine. On July 11, 1873, 29-year-old Alfred proposed to 19-year-old Maria and she accepted. Queen Victoria sent her congratulations but confessed to her diary, ” Felt quite bewildered. Not knowing Marie & realizing that there may still be many difficulties, my thoughts & feelings are rather mixed, but I said from my heart “God bless them”, & I hope and pray it may turn out for Affie’s happiness.”

Queen Victoria was further incensed when Alexander II refused her request to bring Maria to Scotland so she could meet her son’s intended bride before the wedding which would be held in St. Petersburg. In return, Victoria incensed Alexander II by requesting a Church of England marriage ceremony be performed along with the Russian Orthodox one.

Portrait of Maria Alexandrovna sent to Queen Victoria, now part of the Royal Collection; Credit – Royal Collection Trust

A portrait of Maria was sent to Queen Victoria and it arrived at Osborne House on January 18, 1874, a few days before the wedding. Queen Victoria wrote about the painting in her diary: “The face is very pleasing & very like the photographs, so that I should think it must be a good likeness.”

The Wedding Site

The Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia; Credit – By Alex ‘Florstein’ Fedorov, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49250446

After the engagement, one of the issues to be decided was the site of the wedding. In 1858, Queen Victoria insisted that her eldest child Victoria, Princess Royal be married in London as it was “not every day that one marries the eldest daughter of the Queen of England” even though the Princess Royal was marrying a future King of Prussia and German Emperor. Maria’s parents were no different. They insisted that their only daughter would be married in Russia. The wedding site was to be the Grand Church of the Winter Palace. In the photo above of the Winter Palace, the golden cupola of the Grand Church can be seen on the left side of the photo.

I have visited the Winter Palace on the banks of the Neva River in St. Petersburg, Russia and it is truly awe-inspiring. It was the official residence of the Russian Emperors and Empresses from 1732 to 1917. Today, part of the palace houses the State Hermitage Museum, one of the world’s premier art museums. The Winter Palace’s monumental scale was intended to reflect the might and power of Imperial Russia and it is still a mighty and powerful building. It is said to contain 1,786 doors, 1,945 windows, 1,500 rooms, and 117 staircases.

The Grand Church of the Winter Palace; Credit – By Januarius-zick – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42460200

Wedding Guests

There is no guest list but it was noted in Alfred’s biography by John Van der Kiste that there were “thousands of guests.” Queen Victoria did not travel to Russia for the wedding. She was at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight on the wedding day. It was the only wedding of her children that she did not attend. Alfred wanted his mother to feel part of his wedding so he commissioned artist Nicholas Chevalier to record the events of the day. Chevalier created a series of watercolor sketches that he later used to create oil paintings. In addition, Queen Victoria sent Arthur Stanley, Dean of Westminster to conduct the Church of England wedding service. Lady Augusta Stanley, the Dean of Westminster’s wife, born Lady Augusta Bruce, was a good friend of Queen Victoria and one of her ladies-in-waiting and was charged to report back all the details to the Queen.

The following members of Alfred’s family, along with the officiant for the Church of England service along with his wife, and the following members of royal households attended:

- The Prince of Wales, Alfred’s brother, and his wife The Princess of Wales

- Victoria, German Crown Princess, Crown Princess of Prussia, Alfred’s sister, and her husband Friedrich, German Crown Prince, Crown Prince of Prussia

- Prince Arthur, Alfred’s brother

- Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Alfred’s paternal uncle

- Arthur Stanley, Dean of Westminster and Lady Augusta Stanley

- Colonel William Colville, Comptroller of Prince Alfred’s Household

- Sir John Clayton Cowell, Alfred’s former governor

- Sir Howard Elphinstone, Arthur’s governor

It is noted in a contemporary newspaper article that Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark (the future King Frederik VIII) and Prince Alexander of Hesse and by Rhine, the bride’s maternal uncle, signed the marriage register, so they were both present.

We can assume that these members of the Russian Imperial Family, among others, attended:

- Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia, Maria’s father

- Maria Alexandrovna, Empress of All Russia, Maria’s mother, born Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine

- Tsarevich Alexander Alexandrovich, Maria’s brother, the future Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia

- Tsesarevna Maria Feodorovna, wife of Tsarevich Alexander Alexandrovich, born Princess Dagmar of Denmark, sister of Alfred’s sister-in-law the Princess of Wales

- Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, Maria’s brother

- Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, Maria’s brother

- Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, Maria’s brother

- Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich, Maria’s brother

- Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, Maria’s paternal uncle

- Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna, Konstantin Nikolaevich’s wife, born Princess Alexandra of Saxe-Altenburg

- Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, Maria’s paternal uncle

- Grand Duchess Alexandra Petrovna, Nicholas Nikolaevich’s wife, born Duchess Alexandra of Oldenburg

- Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich, Maria’s paternal uncle

- Grand Duchess Olga Feodorovna, Michael Nikolaevich’s wife, born Princess Cecilie of Baden

Groomsmen

Unlike the British tradition, there were no bridesmaids, only groomsmen – Alfred’s brother Arthur and three of Maria’s brothers. Their main job was to hold the gold marriage crowns over the heads of the bride and groom during the Russian Orthodox wedding ceremony. During the Church of England marriage ceremony, Prince Arthur and one of Maria’s brothers acted as Alfred’s supporters.

- Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich

- Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich

- Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich

- Prince Arthur

The Wedding Attire

The Imperial Order of St. Andrew, obverse (left) and reverse (right); Credit – Wikipedia

Prince Alfred wore a Russian naval uniform and the Russian Order of Saint Andrew. Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia had recently given Alfred the honorary rank of Captain in the Russian Navy and Chief of the 2nd Division of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna wore a silver sarafan set with jewels, a traditional dress worn by all Russian imperial brides for their wedding, and the diamond Romanov nuptial tiara, formed like the traditional Russian kokoshnik headdress. In addition, Maria wore the diamond Romanov nuptial crown and an immense purple velvet mantle trimmed with ermine. Lady Augusta Stanley commented about Maria: “…the small graceful head still so childlike, must have ached with the immense weight of jewels, the necklace of diamonds…the most beautiful ones I ever saw, and the gown was studded with them, round the body and the sleeves and down the front of the body and skirt.”

The photo below is not Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna but rather her niece, Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna, the daughter of her brother Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich. The photo was taken on the day of Elena Vladimirovna’s wedding to Prince Nicholas of Greece in 1902. I have not found a photo of Maria Alexandrovna on her wedding day but she would have been dressed as her niece was dressed. Notice on her head the Romanov nuptial tiara, in the front and the Romanov nuptial crown with the cross in the back. The hairstyle is traditional for Romanov brides.

Maria Alexandrovna’s niece Elena Vladimirovna dressed as her aunt would have been dressed on her wedding day; Credit – Wikipedia

The Wedding

The halls of the immense Winter Palace were filled with people and activity. As the imperial procession began, a hush went through the halls. Leading the procession were sixty chamberlains dressed in gold lace, followed by dignitaries wearing their medals and orders. Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia, dressed in a general’s uniform, and his wife Maria Alexandrovna, Empress of All Russia, dressed in a yellow satin dress with a long train, acknowledged the people lining the halls by bowing their heads. Next came Alfred leading Maria while six chamberlains carried the bride’s train. They were followed by members of the Russian Imperial Family, foreign royalty, and members of the Russian court.

Once in the Grand Church, Alfred and Maria stood on a crimson carpet before a lectern on which lay the Gospels in a bejeweled cover. The Metropolitans of Novgorod, Moscow, and Kiev conducted the Russian Orthodox wedding ceremony. After much chanting and low-voiced reading, the gold marriage crowns were brought out. Prince Arthur and one of Maria’s brothers (either Vladimir or Sergei) took the crowns and held them at arm’s length over Alfred and Maria’s heads. Arthur and the Grand Duke frequently changed hands because of the weight of the crowns. Finally, when Arthur was exhausted, Maria’s brother Grand Duke Alexis took his crown.

Alfred and Maria, holding lighted candles, walked three times around the altar and the lectern. The marriage crowns were then placed on a gold plate and carried into the inner chapel. Alfred and Maria followed and walked three times around the altar and then they received Communion. A beautiful, triumphal chant ended the Russian Orthodox service.

Alexander Hall in the Winter Palace, St Petersburg by Eduard Hau (1861); Credit – Wikipedia

The procession then traveled to Alexander Hall, a white hall with purple velvet curtains on the windows. The walls were covered with paintings of Alexander I, Emperor of All Russia and his military battles during the Napoleonic Wars. The window curtains were drawn and the room was lighted with thousands of candles. It is here that the Church of England wedding service took place. Arthur Stanley, Dean of Westminster was waiting to perform the service. Alexander II led his daughter to the altar. Alfred took his place beside Maria, supported by Prince Arthur, one of Maria’s brothers, and four chamberlains. After a chant by a Russian choir, Dean Stanley began the Church of England marriage service. Maria said her vows in perfect English as she had learned the language beginning in early childhood. Before she had entered Alexander Hall for the Church of England service, Maria had been given a bouquet sent by Queen Victoria which contained sprigs from a myrtle tree at Osborne House. Since the wedding of Alfred’s eldest sister Victoria, Princess Royal, it has become a British royal family tradition for bridal bouquets to contain a sprig of myrtle from that tree.

After the Wedding

Nicholas Hall of the Winter Palace by Konstantin Andreyevich Ukhtomsky (1879); Credit – Wikipedia

A wedding banquet for 800 people was held in Nicholas Hall, the largest room in the palace at 11,870 square feet/1,103 square meters. Originally known as the Great Hall, it was renamed the Nicholas Hall after the death of Nicholas I, Emperor of All Russia, and a large equestrian portrait of the late emperor was hung on a wall. The guests had assembled at 4:30 PM and at 5:00 PM, they fell silent as Alexander II, his wife Maria Alexandrovna, Alfred and Maria and other members of the Russian Imperial Family entered Nicholas Hall.

As soon as the imperial procession was seated, the entertainment started. Two of the most renowned operatic sopranos performed: Adelina Patti from Italy and Emma Albani from Canada. While Emma Albani sang an aria from Rigoletto, the cannons from the Peter and Paul Fortress, just across the Neva River, began firing salutes but Miss Albani’s voice soared above the sound of the cannons. The menu included such delicacies as Potage de Gibier à l’Indienne (Wild Indian Game Soup) and Collettes de Perdreaux à la Maréchale Garni de Gelée Muscovite à l’Ananas (partridges garnished with Muscovite jelly with pineapple). At 6:00 PM, the banquet ended but the celebrations were not yet over. Over 3,000 guests attended a ball in the Great Throne Room later in the evening.

St George’s Hall (also referred to as the Great Throne Room); Credit – By Poudou99 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58055018

Alfred and Maria attended the ball but left early to board a train for the fifteen-mile trip to Tsarskoe Selo where they would spend their honeymoon at the Alexander Palace. Alexander II, ever hoping that his daughter would not really go off to live in England, had ordered an elaborate honeymoon suite on the ground floor, hoping that it would persuade the couple to remain in Russia. However, after a short honeymoon, Alfred and Maria left Russia to live in England. The honeymoon suite was kept for Alfred and Maria in hopes that they would change their minds and return to live in Russia. In 1894, it became the bedroom suite of the last Emperor of All Russia, Nicholas II, Maria’s nephew, and his wife Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, born Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine, Alfred’s niece.

Children

Marie with her children; Credit – Wikipedia

Alfred and Marie had five children:

- Prince Alfred, Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1874-1899) – unmarried

- Princess Marie (1875-1938) – married King Ferdinand of Romania, had six children, Romanian and Serbian Royal Families descend from this marriage

- Princess Victoria Melita (1876-1936) – married (1) Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse and by Rhine (divorced), had one child; (2) Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich of Russia, had three children, claimants to the throne of Russia descend from this marriage

- Princess Alexandra (1878-1942) – married Ernst II, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, had issue

- Princess Beatrice (1884-1966) – married Infante Alfonso of Spain, Duke of Galliera, had issue

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred,_Duke_of_Saxe-Coburg_and_Gotha [Accessed 9 Sep. 2019].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchess_Maria_Alexandrovna_of_Russia [Accessed 9 Sep. 2019].

- Mehl, Scott. (2015). Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. [online] Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/prince-alfred-duke-of-edinburgh-duke-of-saxe-coburg-and-gotha/ [Accessed 9 Sep. 2019].

- Mehl, Scott. (2015). Maria Alexandrovna of Russia, Duchess of Edinburgh, Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/grand-duchess-maria-alexandrovna-of-russia-duchess-of-edinburgh-duchess-of-saxe-coburg-and-gotha/ [Accessed 9 Sep. 2019].

- Rct.uk. (2019). The marriage of Prince Alfred and Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna. [online] Available at: https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/exhibitions/russia-royalty-the-romanovs/the-queens-gallery-buckingham-palace/the-marriage-of-prince-alfred-and-grand-duchess-maria-alexandrovna [Accessed 9 Sep. 2019].

- Trove. (1874). THE MARRIAGE OF THE DUKE OF EDINBURGH. – The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954) – 8 Apr 1874. [online] Available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13334461 [Accessed 9 Sep. 2019].

- Van der Kiste, John and Jordaan, Bee. (1995). Dearest Affie: Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, Queen Victoria’s Second Son. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton.

- Van der Kiste, J. (2011). Queen Victoria’s Children. Stroud: The History Press.