by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2018

Maria Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya, Tsaritsa of All Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

The first wife of Alexei I, Tsar of All Russia, Maria Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya was born in Moscow, Russia on April 11, 1624. She was the youngest of the four daughters of the boyar (noble) and diplomat Ilya Danilovich Miloslavsky and his wife Ekaterina Feodorovna Narbekova. Maria was the mother of thirteen children including two Tsars of All Russia, Fyodor III and Ivan V, and Sophia Alexeevna, who served as Regent for her brother Ivan V and half-brother Peter I (the Great).

Maria Ilyinichna had three older sisters:

- Anna Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya (? – 1667), married Boris Ivanovich Morozov, Alexei I’s tutor and advisor, no children

- Ekaterina Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya, married Prince Fyodor Lvovich Volkonsky, statesman and military leader, had two sons

- Irina Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya (? – 1645), married Prince Dmitry Alekseevich Dolgorukov, statesman and military leader, had two children

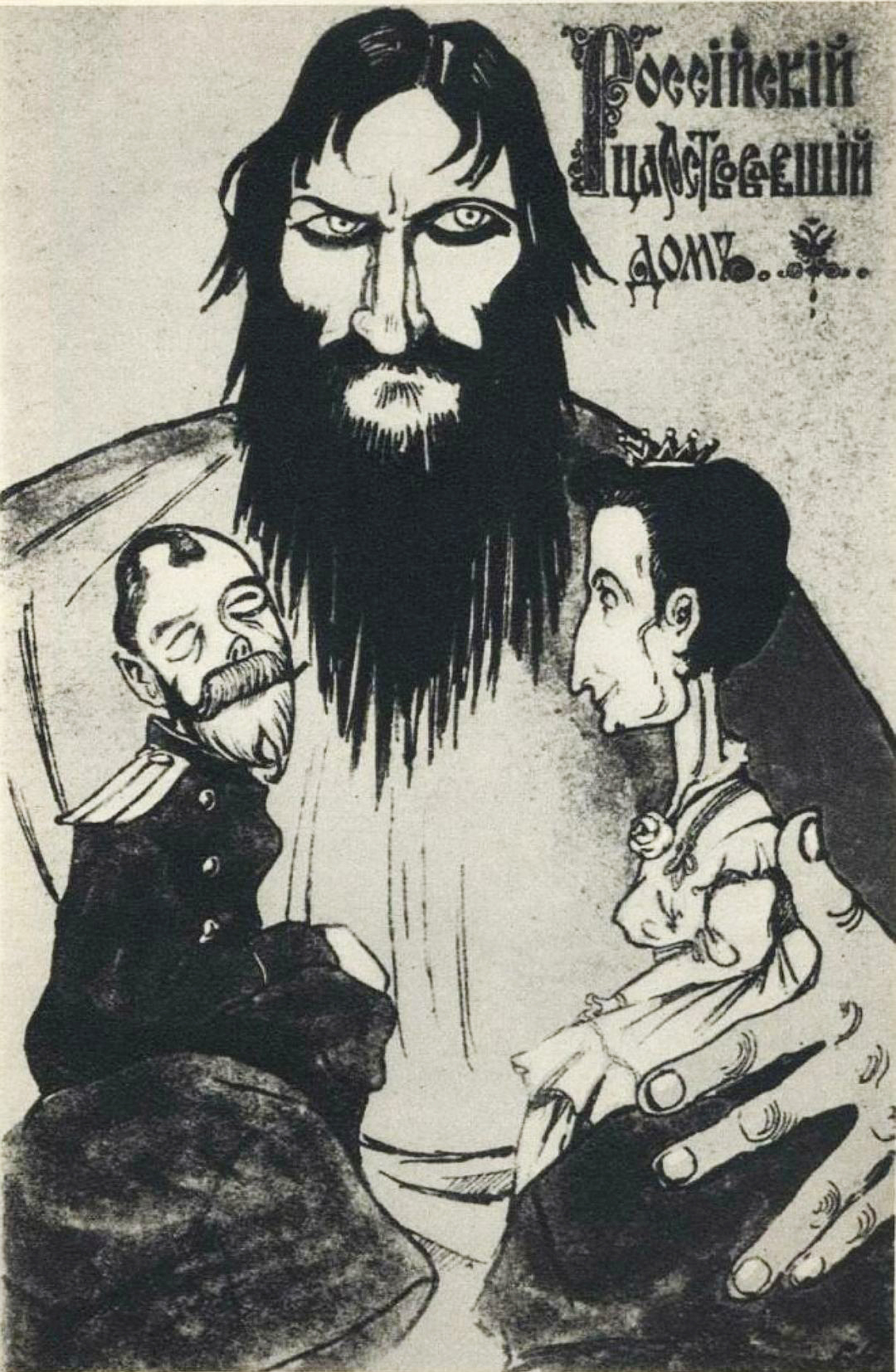

Tsar Alexei chooses his bride by Grigory Sedov; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1647, a bride-show, a custom of Byzantine emperors and Russian tsars used to choose a wife from among the most beautiful maidens of the country, was arranged for Alexei, who had become Tsar of All Russia two years earlier upon the death of his father Michael I, the first ruler of the Romanov dynasty. Nearly two hundred girls were brought to see Alexei. His choice fell upon Euphemia Feodorovna Vsevolozhskaya, the daughter of a statesman and wealthy landowner. However, the proposed wedding was prevented by Boris Ivanovich Morozov, Alexei’s tutor and advisor, who had great power at court. Morozov wanted to be related to the tsar and had a scheme to marry Alexei to Maria Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya, a daughter of Ilya Danilovich Miloslavsky, a supporter of Morozov, while Morozov then married Maria’s eldest sister Anna. Morozov bribed a hairdresser who pulled Euphemia Feodorovna’s hair so hard that she fainted. Then a court physician was bribed to diagnose Euphemia Feodorovna with epilepsy. Her father was accused of concealing the disease, the betrothal was annulled, and the whole Vsevolozhsky family was sent into exile.

The first meeting of Alexis Mikhailovich and Maria Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya; Credit – Wikipedia

Morozov then introduced Alexei to Maria Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya, who was beautiful and declared healthy by the court physicians. The wedding took place on January 16, 1648, in Moscow. Ten days later, Boris Ivanovich Morozov married the new Tsaritsa’s sister Anna Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya, strengthening his position at court.

Maria Ilyinichna Miloslavskaya and Alexei had thirteen children. None of their daughters married. They lived in seclusion in the terem with their sisters and aunts.

- Tsarevich Dmitri Alexeievich (1648–1649); died in infancy

- Tsarevna Yevdokia Alexeievna (1650–1712)

- Tsarevna Marfa Alexeievna (1652–1707)

- Tsarevich Alexei Alexeievich (1654–1670); died unmarried, age 15

- Tsarevna Anna Alexeievna (1655–1659); died in infancy

- Tsarevna Sofia Alexeievna (1657–1704), Regent of Russia (1682–89) for her younger brother Ivan V and younger half-brother Peter I; unmarried

- Tsarevna Ekaterina Alexeievna (1658–1718)

- Tsarevna Maria Alexeievna (1660–1723)

- Fyodor III, Tsar of All Russia (1661–1682); succeeded his father as Tsar of Russia; married (1) Agaphia Simeonovna Gruszewska, no surviving children (2) Marfa Matveievna Apraksina, no children

- Tsarevna Feodosia Alexeievna (1662–1713)

- Tsarevich Simeon Alexeievich (1665–1669); died in early childhood

- Ivan V, Tsar of All Russia (1666–1696); was co-ruler along with his younger half-brother Peter I; married Praskovia Saltykova, had five daughters including Anna, Empress of All Russia

- Tsarevna Yevdokia Alexeievna (born and died 1669)

Tsaritsa Maria Ilyinichna; Credit – Wikipedia

During this time, the life of Russian noblewomen, including the Tsaritsa of All Russia, was not a public one. They were expected to live in seclusion with little contact with men. Maria Ilyinichna was mainly involved in charitable and religious activities such as donating to facilities for the poor, sick, and disabled and supporting the work of Feodor Mikhailovich Rtishchev, a boyar and close friend of Alexei who was famous for his piety and work with the poor. She acted as the protector of the cult of St. Mary of Egypt, who became a patron saint of the Romanov dynasty. At that time, the only church in Moscow devoted to St. Mary of Egypt was at the Sretensky Monastery. Alexei and Maria Ilyinichna commissioned an icon for the monastery St. Alexis, a Man of God and St. Mary of Egypt.

On March 13, 1669, 45-year-old Maria Ilyinichna died of puerperal fever (childbed fever) five days after her most difficult childbirth. Her thirteenth child, Yevdokia Alexeevna, lived for only two days. Maria Ilyinichna and her child were buried at the Ascension Convent, a Russian Orthodox nunnery in the Moscow Kremlin where royal and noblewomen were buried. In 1929, the Ascension Convent was dismantled by the Soviets to make room for the Red Commanders School. At that time, the remains of those buried there were moved to the crypt of the Archangel Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin.

Ascension Convent, Maria Ilyinichna’s original burial place; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Archangel Cathedral, Maria Ilyinichna’s current burial place; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Romanov Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Tsardom of Russia/Russian Empire Index

- Romanov Births, Marriages and Deaths

- Romanov Burial Sites

- Romanovs Killed During the Russian Revolution

- Romanovs Who Survived the Russian Revolution

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. (2017). Maria Miloslavskaya. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Miloslavskaya [Accessed 4 Dec. 2017].

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1981). The Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias. New York, NY.: Doubleday.

- Ru.wikipedia.org. (2017). Милославская, Мария Ильинична. [online] Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9C%D0%B8%D0%BB%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B2%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%8F,_%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%8F_%D0%98%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%87%D0%BD%D0%B0 [Accessed 4 Dec. 2017].