by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2025

Brunswick Cathedral with the Brunswick Lion in the foreground; Credit – By Kassandro Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1770712

Originally a Roman Catholic church, Brunswick Cathedral (Braunschweiger Dom in German) is now a Lutheran church in Brunswick in the German state of Lower Saxony. The cathedral was founded in 1173 by Heinrich der Löwe (Henry the Lion – Heinrich III, Duke of Saxony from 1142 to 1180 and also Heinrich XII, Duke of Bavaria from 1156 to 1180). Heinrich built the cathedral as a burial place for himself and his second wife Matilda of England, Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria, the eldest daughter of King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine, and their successors.

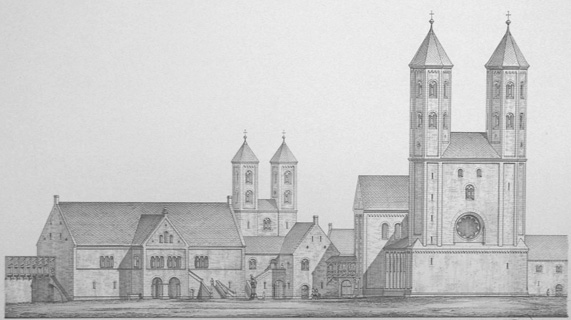

Dankwarderode Castle on the left, Brunswick Cathedral on the right; Credit – Wikipedia

Brunswick Cathedral was built between 1173 and 1195 on the Burgplatz (Castle Square) in Brunswick, adjacent to Dankwarderode Castle where Heinrich the Lion built his palace circa 1160 – 1175. There was direct access from the upper floor of Dankwarderode Castle to the north transept of Brunswick Cathedral. When Brunswick Cathedral was officially consecrated in 1226, it was dedicated to Saint Thomas Becket, Saint Blaise, and Saint John the Baptist. Matilda was a strong supporter of the 1173 canonization as a saint of Thomas Becket who had been murdered in Canterbury Cathedral by four of her father’s knights in 1170. See Unofficial Royalty: Canterbury Cathedral for more information.

The central nave with the tomb of Heinrich the Lion and Matilda of England in the foreground; Credit – Di Photo by PtrQs, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=81519784

A 1900 painting of Brunswick Cathedral; Credit – Wikipedia

Brunswick Cathedral was built initially built as a three-aisled Romanesque pillar basilica. The cathedral was expanded and rebuilt several times, but the nave, transept, and choir are largely preserved from the 12th-century original building.

Tomb of Matilda and Heinrich with a memorial plaque for their son Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor; Credit – Von Brunswyk – DE:Wiki, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4217450

On June 28, 1189, Matilda died at Brunswick at the age of 33, about a week before her father King Henry II of England died. She was buried at the still incomplete Brunswick Cathedral. Heinrich, died on August 6, 1195, aged 65 – 66, in Brunswick, and was buried next to Matilda. Their tomb is the oldest double grave of a married couple in Germany. Their effigies are still the originals, made in the first half of the thirteenth century.

Crypt of Heinrich the Lion, Sarcophagus of Heinrich (left) and Matilda (right); Credit – Von Brunswyk, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18904214

Brunswick Cathedral and the Nazis

During the Nazi regime, the Nazis used Heinrich the Lion and Brunswick Cathedral for ideological and propaganda purposes. In 1147, Heinrich the Lion’s Wendish Crusade against Polabian Slavs, also known as Wends, who lived northeast of Brunswick, resulted in their subjugation and the colonization of their territory. The Nazis tried to make Henry the Lion appear as the pioneer of their ideology. Between 1935 and 1940, the cathedral’s 19th-century interior furnishings were completely removed and the building was partially structurally and aesthetically altered to reflect Nazi ideology. The tombs of Heinrich the Lion and his wife Matilda were opened, supposedly for archaeological work, but the work lacked any scientific basis. The opening of the tombs was used as propaganda to bring attention to Heinrich the Lion and what the Nazis wanted him to represent. All this was done under the supervision of Dietrich Klagges, Prime Minister of the Free State of Brunswick from 1933 to 1945.

Adolf Hitler secretly visited Brunswick Cathedral on July 17, 1935 to observe the work. The visit did not go as Klagges intended. After the tour, Hitler declared that from now on he would be the only one to decide on the type and extent of the construction work for the conversion of the Brunswick Cathedral into a Nazi shrine. All work orders given by Klagges were canceled. To Hitler’s great annoyance, news of his secret visit quickly spread among the local people. Hitler left Brunswick after just a few hours and never returned. After World War II ended, the structural and design changes the Nazis had made to Brunswick Cathedral were largely reversed where possible, and the cathedral was able to serve as a Lutheran place of worship again.

Burials at Brunswick Cathedral

The crypt at Brunswick Cathedral; Credit – By TeWeBs – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=147494393

Perhaps the two most famous burials at Brunswick Cathedral besides Heinrich the Lion and Matilda of England, are their son Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor (1175 -1218) and Caroline of Brunswick, Queen of the United Kingdom (1768 – 1821), the wife of King George IV of the United Kingdom.

Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor

The seal of Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor; Credit – Wikipedia

Otto was the third son of Heinrich the Lion, Duke of Bavaria, Duke of Saxony and Matilda of England. Otto’s maternal grandparents were King Henry II of England and Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right. Otto’s maternal uncles were King Richard I of England (the Lionheart) and King John of England. Otto spent most of his early life in England and France. He was a supporter of his uncle Richard, who created Otto Count of Poitou in 1196. With Richard’s support, he was elected King of the Romans in 1198, a step toward being Holy Roman Emperor. In 1209, Otto went to Rome to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Innocent III.

In 1210, Otto attempted to add the Kingdom of Sicily to the Holy Roman Empire, against the wishes of Pope Innocent III, who excommunicated him. Otto allied with his uncle King John of England, Count Ferrand of Flanders, Count Renaud of Boulogne, Duke Henri I of Brabant, Count William I of Holland, Duke Theobald I of Lorraine, and Duke Henry III of Limburg in an alliance against France during the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. The coalition was soundly defeated at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214 when Otto was carried off the battlefield by his wounded and terrified horse, causing his forces to abandon the battlefield. The defeat forced Otto to withdraw to his home in Brunswick, allowing Ferderico, King of Sicily to take the German cities of Aachen and Cologne, depose Otto, and become Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich II. Otto died on May 19, 1218, aged 42–43, at Harzburg Castle, now in Bad Harzburg in the German state of Lower Saxony. There is a memorial plaque to Otto on the floor near the tombs of his parents which can be seen in a photo above.

Caroline of Brunswick, Queen of the United Kingdom

Caroline of Brunswick, Queen of the United Kingdom; Credit – Wikipedia

Caroline of Brunswick was the daughter of Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Augusta of Great Britain, the elder sister of King George III of the United Kingdom. In 1795, Caroline of Brunswick married her first cousin, the future King George IV of the United Kingdom. The marriage of Caroline and George is one of the worst-ever royal marriages. Upon first seeing Caroline, George said to his valet, “Harris, I am not well; pray get me a glass of brandy.” Caroline said George was fat and not as handsome as his portrait. It is doubtful that the couple spent more than a few nights together as husband and wife. Their only child Princess Charlotte of Wales was born nine months later. Caroline and George found each other equally unattractive and never lived together or appeared in public together. Caroline was ignored at the court and lived more or less under house arrest. After two and a half years, she left the court and lived for ten years in a Montagu House in Blackheath, London. Caroline was denied any part in raising her daughter Charlotte and only saw her occasionally. Sadly, Charlotte predeceased both her parents, dying in childbirth in 1817 at the age of 21, along with her son. Had Charlotte lived, she would have succeeded her father on the throne.

When King George III died in January 1820, Caroline was determined to return to England and assert her rights as queen. King George IV was determined to be rid of Caroline and his government introduced a bill in Parliament, the Pains and Penalties Bill 1820, to strip Caroline of the title of queen consort and dissolve her marriage. The reading of the bill in Parliament was effectively a trial of Caroline. On November 10, 1820, a final reading of the bill took place, and the bill passed by 108–99. Prime Minister Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool then declared that since the vote was so close and public tensions so high, the government would withdraw the bill.

King George IV’s coronation was set for July 19, 1821, but no plans had been made for Caroline to participate. On the day of the coronation, Caroline went to Westminster Abbey, was barred at every entrance, and finally left. Three weeks later on August 7, 1821, Caroline died at the age of 53, most likely from a bowel obstruction or cancer. Before her death, Caroline requested that she be buried in her native Brunswick. Caroline was interred at Brunswick Cathedral next to her father. Her casket bears the inscription, “Here lies Caroline, the Injured Queen of England.”

Tomb of Queen Caroline in the crypt at Brunswick Cathedral: Credit – www.findagrave.com

This does not purport to be a complete list of the burials at Brunswick Cathedral.

- Gertrud the Elder of Brunswick, Margravine of Frisia (? – 1077), founder of St. Blasius Church, the previous church on the site of Brunswick Cathedral, wife of Liudolf of Brunswick, Margrave of Frisia, Count of Brunswick

- Gertrude the Younger of Brunswick (circa 1058 – 1117), sister of Ekbert II, Count of Brunswick and Margrave of Meissen and wife of Dietrich II, Count of Katlenburg

- Heinrich, Margrave of Frisia, and Heinrich I, Margrave of the Saxon Ostmark, founder of the Aegidien Monastery in Brunswick

- Ekbert II, Count of Brunswick and Margrave of Meissen (circa 1060 – 1090)

- Heinrich the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria (1129 – 1195)

- Matilda of England, Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria (1156 – 1189), second wife of Heinrich the Lion, daughter of the English King Henry II of England

- Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor (1175 – 1218), son of Heinrich the Lion

- Beatrice of Hohenstaufen (1198 – 1212), wife of Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor

- Otto I, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (circa 1204 – 1252)

- Albrecht I, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1236 – 1279)

- Elizabeth of Brabant (1243 – 1261), daughter of Henri II, Duke of Brabant, first wife of Albrecht I, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Agnes of Brandenburg (1297 – 1334), wife of Otto the Mild, Duke of Brunswick and Lüneburg

- Friedrich I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (circa 1357 – 1400)

- Cäcilie of Brandenburg (1405 – 1449), daughter of Friedrich I, Elector of Brandenburg, wife of Wilhelm I of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel

- Henrich IV, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1463 – 1514), died at the Siege of Leer

- Catherine of Pomerania-Wolgast (circa 1465 – 1526), wife of Henrich IV, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Heinrich V, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1489 – 1568)

- Rudolf Augustus, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1627 – 1704)

- Christine Elizabeth of Barby-Mühlingen (1634 – 1681), first wife of Rudolf Augustus, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- Rosine Elisabeth Menthe, (1663–1701), second wife of Rudolf Augustus, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- Ferdinand Albrecht I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern (1636 – 1687)

- Ludwig Rudolph, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1671–1735)

- Christine Louise of Oettingen-Oettingen (1671–1747), wife of Ludwig Rudolph, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- August Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern (link in German) (1677 – 1704), son of Ferdinand Albrecht I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern

- Ferdinand Albrecht II, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1680 – 1735)

- Antoinette Amalia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1696 – 1762), daughter of Ludwig Rudolph, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and wife of Ferdinand Albrecht II, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Ferdinand Christian of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern, Provost of Brunswick Cathedral (1682–1706), son of Ferdinand Albrecht I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern

- Ernst Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern (1682 – 1746), son of Ferdinand Albrecht I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern, son of Augustus the Younger, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Heinrich Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern (1684 – 1706), son of Ferdinand Albrecht I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern, died at the Siege of Turin

- Karl I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1713 – 1780)

- Philippine Charlotte of Prussia (1716 – 1801), daughter of King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia and wife of Karl I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- Ludwig Ernst of Brunswick-Lüneburg-Bevern (1718 – 1788) son of Ferdinand Albrecht II, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg,

- Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1721 – 1792), son of Ferdinand Albrecht II, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Friedrich Georg (1723 – 1776), Canon of Lübeck, son of Ernst Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern

- Albrecht of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (link in German) (1725–1745), son of Ferdinand Albrecht II, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, died at the Battle of Soor

- Friedrich Wilhelm (1731–1732), infant son of Ferdinand Albrecht II, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Friedrich Franz of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1732 – 1758), son of Ferdinand Albrecht II, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, killed at the Battle of Hochkirch

- Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick (1735 – 1806), died at the Battle of Jena and Auerstedt during the Napoleonic Wars

- Prince Maximilian Julius Leopold of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1752 – 1785), son of Karl I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- Caroline of Brunswick, Queen of the United Kingdom (1768 – 1821), daughter of Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, wife of King George IV of the United Kingdom

- Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1771 – 1815), son of Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick and Princess Augusta of Great Britain, died at the Battle of Quarte Bra during the Napoleonic Wars

- Wilhelm, Duke of Brunswick (1806 – 1884)

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Autoren der Wikimedia-Projekte. (2005). Kirchengebäude in Braunschweig, Niedersachsen. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Braunschweiger_Dom

- Der Braunschweiger Dom: Domkirche. (2024). Braunschweigerdom.de. https://www.braunschweigerdom.de/ueberdom

- Dom Saint Blasius in Braunschweig, Lower Saxony – Find a Grave Cemetery. (2021). Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2098911/dom-saint-blasius

- Flantzer, Susan. (2017). Matilda of England, Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria. Unofficial Royalty. https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/matilda-of-england-duchess-of-saxony/

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2024). Brunswick Cathedral. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation.

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2024). Henry the Lion. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation.