by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2023

Queen Consort Camilla will be crowned with Queen Mary’s Crown, 1911 Credit – Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Check out all our British coronation articles at the link below:

A queen consort is the wife of a reigning king. She shares her husband’s rank and status and holds the feminine equivalent of the king’s titles but does not share the king’s political powers. In the United Kingdom, a Queen Consort is styled Her Majesty Queen <first name>. A Queen Regnant is a female sovereign, equivalent in rank to a king, who reigns in her own right, such as Queen Victoria or Queen Elizabeth II.

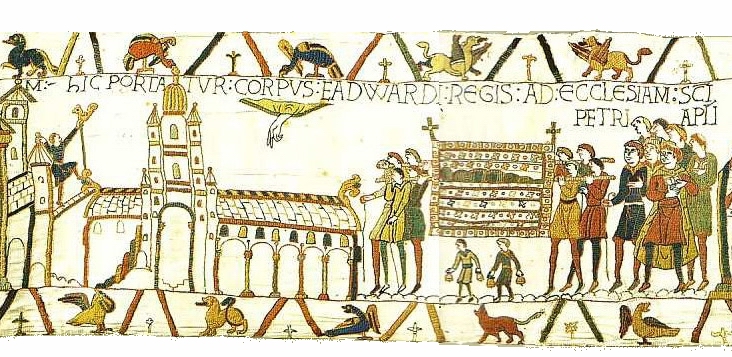

Twenty-eight queen consorts have been crowned in Westminster Abbey since the Norman Conquest in 1066. A number of queen consorts were not crowned with their husbands but were crowned in a separate coronation ceremony. The reasons vary from not being married when their husbands became king, not being in England at the time, pregnancy, and illness. Eight queen consorts were never crowned. Margaret of France, the second wife of King Edward I, was never crowned, making her the first queen consort since the Norman Conquest in 1066 not to be crowned. King Henry VIII apparently did not feel the need to have his last four wives crowned. Three of them were queens for a short time: Jane Seymour (15 months, died), Anne of Cleves (7 months, divorced), Catherine Howard (16 months, beheaded). Henry VIII’s last wife Catherine Parr (survived) was queen for a bit longer, 2 ½ years. Henrietta Maria of France, wife of King Charles I, and Catherine of Braganza, wife of King Charles II, were not crowned because they were Roman Catholic and did not want to participate in a Church of England ceremony. King George IV’s estranged wife Caroline of Brunswick was prevented from being crowned with him. When she showed up at Westminster Abbey on the day of the coronation, she was turned away.

Unless otherwise noted, all pictures, portraits, and photos are from Wikipedia.

********************

Matilda of Flanders, Queen of England

Statue of Matilda of Flanders in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris, France

Matilda’s husband was the illegitimate child of Robert I the Magnificent, Duke of Normandy and his mistress Herleva of Falaise, and got his crown by conquest. Matilda brought a much-needed royal pedigree into her marriage that gave her husband more credibility. She was a direct descendant of the Anglo-Saxon king, Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, and was the maternal granddaughter of King Robert II of France. Matilda’s father was the powerful Baldwin V, Count of Flanders. The liturgy for Matilda’s coronation stressed her power as a queen and that she had been chosen by God for the position. It further stressed that Matilda shared her husband’s royal authority and that this authority and her virtues were a blessing sent to those she now ruled.

********************

Matilda of Scotland, Queen of England

Edith of Scotland and King Henry I were married on November 11, 1100, at Westminster Abbey. Following the wedding ceremony, Edith was crowned Queen of England and took the regnal name Matilda in honor of Henry’s deceased mother Matilda of Flanders.

********************

Adeliza of Louvain, Queen of England

- Daughter of Godfrey I, Count of Louvain and his first wife Ida of Chiny

- Born: circa 1103, in Louvain, County of Louvain, now in the province of Flemish Brabant, Belgium

- Husband: King Henry I of England, his second wife

- Coronation: February 3, 1122 at Westminster Abbey in a separate ceremony

- Crowned by: Ralph d’Escures, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: April 23, 1151

- Unofficial Royalty: Adeliza of Louvain, Queen of England

King Henry’s wife Matilda of Scotland had died in 1118 and he was in need of a male heir, so a second marriage became a necessity. King Henry I of England, aged 53, married the 18-year-old Adeliza of Louvain on January 24, 1121, at Windsor Castle in Windsor, England. Adeliza was crowned a week after the wedding but she did not provide her husband with an heir.

********************

Matilda of Boulogne, Countess of Boulogne, Queen of England

Matilda was Countess of Boulange in her own right. On December 1, 1135, King Henry I of England died. Henry I’s nephew Stephen of Blois, quickly crossed from Boulogne to England, accompanied by his military household. With the help of his brother, Henry of Blois who was Bishop of Winchester, Stephen seized power in England and was crowned king on December 22, 1135. Matilda was unable to accompany her husband because she was pregnant, so she was crowned on Easter Day, March 22, 1136.

********************

Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, Queen of England

- Daughter of William X, Duke of Aquitaine and Aenor de Châtellerault

- Born: circa 1122 in either Poitiers, Bordeaux, or Nieul-sur-l’Autis, all cities in her father’s lands, all now in France.

- Husband: King Henry II of England

- Coronation: December 19, 1154 at Westminster Abbey, crowned with her husband

- Crowned by: Theobald of Bec, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: April 1, 1204

- Unofficial Royalty: Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, Queen of England

Eleanor was Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right. With the accession of her husband as King Henry II, England had its first undisputed king for over a century. Traveling from his French possessions (Henry was also Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, and Count of Nantes), Henry II arrived in England on December 8, 1154. He immediately took the oaths of loyalty from the barons, Eleven days later, Henry and his very pregnant wife Eleanor were crowned at Westminster Abbey.

********************

Berengaria of Navarre, Queen of England

Berengaria and King Richard I were to have married in Sicily, but Richard postponed the wedding and set off for the Holy Land along with Berengaria and his widowed sister Joan, Queen of Sicily who were on a separate ship. Two days after setting sail, Richard’s fleet was hit by a strong storm. Several ships were lost and others were way off course. Richard landed safely in Crete, but the ship Berengaria and Joan were on was marooned near Cyprus. Berengaria and Joan were about to be captured by the ruler of Cyprus when Richard’s ships rescued them. On May 12, 1191, King Richard I of England married Berengaria at the Chapel of St George in Limassol, Cyprus, and after the wedding ceremony, Berengaria was crowned Queen of England. Then Richard, his new wife Berengaria, and his widowed sister Joan, Queen of Sicily accompanied Richard throughout the Crusade.

********************

Isabella, Duchess of Angoulême, Queen of England

Isabella was Duchess of Angoulême in her own right. She was crowned two months after she married King John.

********************

Eleanor of Provence, Queen of England

Eleanor and her four sisters all made excellent marriages and were all queens via these marriages. On January 14, 1236, King Henry III and Eleanor were married at Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, England. They then immediately traveled to London where Eleanor was crowned six days later. Following Eleanor’s coronation, a magnificent banquet was held with the entire English nobility attending.

********************

Eleanor of Castile, Queen of England

In 1270, Edward, then the heir to the throne, had gone off on the Crusades accompanied by his wife Eleanor of Castile, and at the time of his father’s death in 1272, he was in Sicily making his slow way back to England. The new King Edward I thought England was safe under his mother’s regency and a royal council, so he did not hurry back to England. On his way back to England, King Edward I visited Pope Gregory X in Rome and King Philip III of France in Paris and suppressed a rebellion in Gascony. He finally arrived back in his kingdom on August 2, 1274. On August 19, 1274, King Edward I and his wife Eleanor were crowned at Westminster Abbey.

********************

Margaret of France, Queen of England

Statue of Margaret of France, Queen of England at Lincoln Cathedral

Margaret was the first uncrowned Queen Consort since the Norman Conquest. She was not crowned because of financial constraints. However, not being crowned did not affect her status as Queen Consort. She even appeared publicly wearing a crown even though she had not received one during a formal coronation

********************

Isabella of France, Queen of England

King Edward II decided to delay his coronation until after his marriage. After he married Isabella of France on January 25, 1308, at Boulogne Cathedral in France, the newlyweds returned to England in February, where Edward II ordered Westminster Palace to be lavishly decorated for their coronation celebrations. Henry Woodlock, Bishop of Winchester was the officiant at the coronation, organized by Piers Gaveston, Edward II’s favorite. Woodlock had received a special commission from the exiled Robert Winchelsey, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was an opponent of King Edward II. English and French nobles attended the magnificent ceremony and the celebrations which followed. However, the celebrations were disrupted by the large crowds of eager spectators who surged into the palace, knocking down a wall, and forcing Edward II to flee for his safety.

********************

Philippa of Hainault, Queen of England

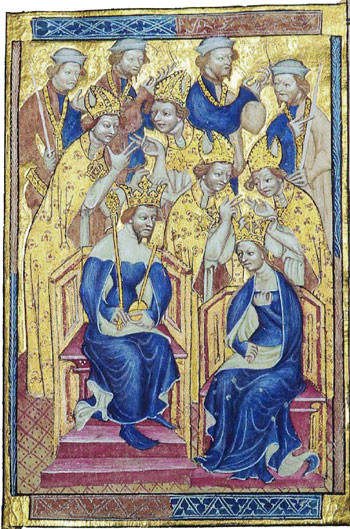

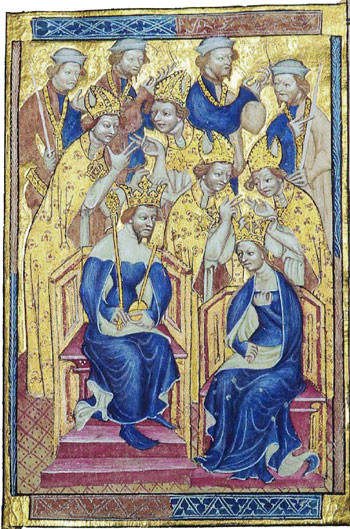

Isabella of Hainault’s coronation

- Daughter of William I, Count of Hainault (also Count of Holland, Count of Avesnes and Count of Zeeland) and Joan of Valois

- Born: June 24, 1314 in Valenciennes, County of Hainault, now in France

- Husband: King Edward III of England

- Coronation: February 18, 1330 at Westminster Abbey, in a separate ceremony

- Crowned by: Simon Mepham, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: August 15, 1369

- Unofficial Royalty: Philippa of Hainault, Queen of England

Philippa married King Edward III on January 24, 1328, but her coronation was delayed for two years because her mother-in-law did not want to give up her status as first lady of the land. Philippa was crowned on February 18, 1330, at Westminster Abbey, when she was almost five months pregnant with her first child.

********************

Anne of Bohemia, Queen of England

Richard II with his wife Anne of Bohemia

- Daughter of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia, and his fourth wife Elizabeth of Pomerania

- Born: May 11, 1366, in Prague, Bohemia, now in the Czech Republic

- Husband: King Richard II of England, first wife

- Coronation: January 22, 1382 at Westminster Abbey, in a separate ceremony

- Crowned by: William Courtenay, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: June 7, 1394

- Unofficial Royalty: Anne of Bohemia, Queen of England

Anne of Bohemia was crowned on January 22, 1382, two days after her wedding to King Richard II. Tournaments were held for several days after the wedding and Anne’s coronation in celebration. Anne and Richard II then made a tour of England staying at many major abbeys as they traveled.

********************

Isabella of Valois, Queen of England

Richard II of England receiving his seven-year-old bride Isabella of Valois from her father Charles VI of France

- Daughter of King Charles VI of France and Isabeau of Bavaria

- Sister of Catherine of Valois, wife of King Henry V (see below)

- Born: November 9, 1389, at the Louvre Palace in Paris, France

- Husband: King Richard II of England, his second wife

- Coronation: January 8, 1397 at Westminster Abbey, in a separate ceremony

- Crowned by: Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: September 13, 1409

- Unofficial Royalty: Isabella of Valois, Queen of England

On November 1, 1396, at the Church of St. Nicholas in Calais, then possession of England, now in France, the nearly seven-year-old Isabella married 29-year-old Richard. Richard and Isabella left for England a few days later and on November 23, 1396, she made her state entry into London. The crowds in London were so great, that people were crushed to death on London Bridge. Isabella was crowned at Westminster Abbey on January 8, 1397. Due to Isabella’s young age and Richard II’s death (murder?) in 1400, the marriage was never consummated. Isabella married her cousin Charles of Orléans in Compiègne, France on June 29, 1406. At the age of 19, Isabella died on September 13, 1409, a few hours after giving birth to her only child, a daughter named Joan.

********************

Joan of Navarre, Queen of England

Tomb of Joan of Navarre and her husband King Henry IV in Canterbury Cathedral; Credit: © Susan Flantzer

- Daughter of Charles II, King of Navarre and Jeanne of Valois,

- Born: circa 1368 in Pamplona in the Kingdom of Navarre, now in Spain

- Husband: King Henry IV of England, his second wife. Henry IV’s first wife Mary de Bohun, Countess of Northampton, Countess of Derby, the mother of his children, died before he became king.

- Coronation: February 26, 1403 at Westminster Abbey, in a separate ceremony

- Crowned by: Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: June 10, 1437

- Unofficial Royalty: Joan of Navarre, Queen of England

In 1398, on a visit to France, to the court of Brittany, Henry met his future second wife Joan of Navarre, the widow of Jean V, Duke of Brittany. Joan of Navarre had not forgotten Henry. Apparently, Henry had made a good impression on her and she became determined to marry him if the opportunity should arise. In 1402, after Joan’s son came of age and could rule Brittany on his own, she sent an emissary to England to arrange a marriage with King Henry IV. Henry was agreeable to the marriage and a proxy marriage was held on April 3, 1402, with Joan’s emissary standing in for the bride. Joan left France for England in January of 1403 with her two youngest daughters and then traveled to Winchester where Henry met her and they were married at Winchester Cathedral on February 7, 1403. They then traveled to London where Joan’s coronation was held at Westminster Abbey on February 26, 1403.

********************

Catherine of Valois, Queen of England

On June 2, 1420, Catherine married King Henry V at Troyes Cathedral in France. The marriage was the result of a peace treaty between England and France during the Hundred Years’ War. Despite the peace treaty, fighting still continued and Catherine spent the first few months of her marriage accompanying Henry from battle to battle. Eventually, the couple returned to England, and Catherine was crowned Queen of England at Westminster Abbey on February 23, 1421. Their marriage was short. King Henry V died from dysentery, a disease that killed more soldiers than battle, on August 31, 1422, at the age of 35, leaving a nine-month-old son he had never seen to inherit his throne as King Henry VI.

Catherine has another footnote in royal history, one that made her the ancestor of all British monarchs since King Henry VIII and many other European royal families, past and present. With Catherine being a young widow and with apparently no chance of remarriage, it should not seem unusual that an amorous relationship would be likely. Owen ap Maredudd ap Tudor, a Welsh soldier and courtier, served in Catherine’s household and they began a relationship. There is much debate as to whether Catherine and Owen married. They had at least four children including Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond who married Lady Margaret Beaufort, a descendant of King Edward III of England. Edmund Tudor and Lady Margaret Beaufort had one son Henry Tudor, the future King Henry VII, the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

********************

Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England

- Daughter of René, Duke of Anjou and Isabella, Duchess of Lorraine in her own right

- Born: March 23, 1430, at Pont-à-Mousson, Duchy of Lorraine, now in France

- Husband: King Henry VI of England

- Coronation: May 30, 1445 at Westminster Abbey, in a separate ceremony

- Crowned by: John Stafford, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: August 25, 1482

- Unofficial Royalty: Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England

King Henry VI lacked any kind of administrative skills which left him open to the machinations of his advisers. When it was time for him to marry, his advisers persuaded Henry that the way to achieve peace with France was to marry Margaret of Anjou, the niece of King Charles VII of France. The couple was married at Titchfield Abbey in England on April 23, 1445. Margaret was crowned Queen Consort of England on May 30, 1445, at Westminster Abbey. She was to prove as strong as Henry was weak. Margaret was a leading figure on the Lancastrian side in the Wars of the Roses and was known for her courage and ambition. After defeat by the Yorkist Edward IV in 1471 and the deaths of her husband and son, she returned to France, dying in poverty

********************

Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of England

The widow of Sir John Grey of Groby (Elizabeth and her first husband are the great-great-grandparents of the ill-fated Lady Jane Grey), Elizabeth first came to the attention of King Edward IV when she petitioned him for the restoration of her husband’s forfeited land. Traditionally, the wedding is said to have taken place at Elizabeth’s family home in Northamptonshire on May 1, 1464. Elizabeth was crowned queen in Westminster Abbey on May 26, 1465.

After the death of her husband in 1483, Elizabeth remained influential even after her son, briefly King Edward V of England, was deposed by her brother-in-law King Richard III. Elizabeth’s sons, the deposed King Edward V and Richard Duke of York – the Princes in the Tower – disappeared and their fate is unknown. Elizabeth played an important role in securing the accession of Henry VII, the first Tudor king, who married Elizabeth’s eldest daughter Elizabeth of York. Through her daughter, Elizabeth Woodville was the grandmother of King Henry VIII.

********************

Anne Neville, Queen of England

Anne’s father, known as “the Kingmaker,” was one of the major players in the Wars of the Roses, originally on the Yorkist side but later switching to the Lancastrian side. Both Anne’s parents were descendants of King Edward III of England. Anne’s husband Richard, Duke of Gloucester, the brother of King Edward IV, deposed his nephew King Edward V. Richard and Anne’s coronation occurred on July 6, 1483, just ten days after Richard III’s accession. The day before the coronation, Richard and Anne rode in procession from the Tower of London to the Palace of Westminster. On their coronation day, King Richard III and Queen Anne walked barefoot on a red carpet to Westminster Abbey. Queen Anne’s train was carried by Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby whose son would become King Henry VII after King Richard III lost his crown and his life at the Battle of Bosworth Field, just five months after Anne’s death.

********************

Elizabeth of York, Queen of England

- Daughter of King Edward IV of England and Elizabeth Woodville

- Born: February 11, 1466, at the Palace of Westminster in London, England

- Husband: King Henry VII of England

- Coronation: November 25, 1487 at Westminster Abbey, in a separate ceremony

- Crowned by: Cardinal John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: February 11, 1503, her 37th birthday, from puerperal fever (childbed fever)

- Unofficial Royalty: Elizabeth of York, Queen of England

Elizabeth of York holds a unique position in British royal history. She was the daughter of King Edward IV, the sister of King Edward V, the niece of King Richard III, the wife of King Henry VII, the mother of King Henry VIII, and the grandmother of King Edward VI, Queen Mary I and Queen Elizabeth I. Her great-granddaughter was Mary, Queen of Scots whose son, King James VI of Scotland, succeeded Queen Elizabeth I as King James I of England. Through this line, the British royal family and other European royal families can trace their descent from Elizabeth of York.

On August 22, 1485, Henry Tudor defeated King Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field and became King Henry VII, the first Tudor king of England. Elizabeth of York and Henry Tudor married on January 18, 1486, at the Palace of Westminster. Elizabeth was crowned Queen Consort of England on November 25, 1487 at Westminster Abbey.

********************

Catherine of Aragon, Queen of England

King Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon were married on June 11, 1509, and crowned together thirteen days later. Read more about their coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon.

********************

Anne Boleyn, Queen of England

- Daughter of Thomas Boleyn (later 1st Earl of Wiltshire, 1st Earl of Ormond, 1st Viscount Rochford) and Lady Elizabeth Howard, the eldest daughter of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk

- Born: between 1501 – 1507 at either Blicking Hall in Norfolk, England or Hever Castle in Kent, England

- Husband: King Henry VIII of England

- Coronation: crowned June 1, 1533 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: Beheaded May 19, 1536

- Unofficial Royalty: Anne Boleyn, Queen of England

Anne was crowned at Westminster Abbey on June 1, 1533. Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn are the only wives of Henry VIII to have coronations. Anne is the only Queen Consort ever to be crowned with St. Edward’s Crown. There was a rush for Anne to be crowned as she was pregnant and there was some question about whether the child (the future Queen Elizabeth I) had been conceived before or after the marriage ceremony. Anne was quite unpopular and Henry VIII wanted to cement her status. The day before her coronation, Anne, wearing white and a gold coronet on her head, participated in a procession through the streets of London. She was seated in a litter of white cloth of gold while the barons of the Cinque Ports held a canopy of cloth of gold over her head.

********************

Jane Seymour, Queen of England

********************

Anne of Cleves, Queen of England

********************

Catherine Howard, Queen of England

********************

Catherine Parr, Queen of England

After the death of King Henry VIII, Catherine Parr married Thomas Seymour, brother of Henry VIII’s late third wife Jane Seymour. Catherine and Thomas had fallen in love before her marriage to Henry VIII, and the two had hoped to marry. However, when Henry VIII began to show an interest in Catherine, she felt it was her duty to choose Henry’s proposal of marriage over Thomas Seymour’s. In August 1548, Catherine and Seymour had a daughter, but tragically Catherine died on September 5, 1548, of puerperal fever (childbed fever). Her daughter Mary Seymour appears to have died young. Six months after Catherine’s death, Thomas Seymour was beheaded for treason.

********************

The following Stuart monarchs of England were also Kings/Queens of Scots until 1707 when Scotland and England were united into a single kingdom called Great Britain: James I, Charles I, Charles II, James II, Mary II, William III, and Anne. The wives of James I, Charles I, Charles II, and James II held the title Queen of Scots in addition to Queen of England.

Anne of Denmark, Queen of England

The coronation of King James I of England and his wife Anne of Denmark was on July 25, 1603 at Westminster Abbey. Read about their coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of James I and Anne.

********************

Henrietta Maria of France, Queen of England

********************

Catherine of Braganza, Queen of England

********************

Maria Beatrice of Modena, Queen of England

- Daughter of Alfonso IV d’Este, Duke of Modena and Reggio, and Laura Martinozzi

- Born: October 5, 1658 at the Ducal Palace in Modena, Duchy of Modena, now in Italy

- Husband: King James II of England, second wife. James II’s first wife Anne Hyde, Duchess of York, mother of Queen Mary II and Queen Anne, died before he became king.

- Coronation: April 23, 1685 at Westminster Abbey, crowned with her husband

- Crowned by: William Sancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: May 7, 1718

- Unofficial Royalty: Maria Beatrice of Modena, Queen of England

On April 23, 1685 at Westminster Abbey, King James II and his second wife Maria Beatrice of Modena were crowned in a service that omitted Communion as James and Maria Beatrice were Roman Catholic. The previous day, King James II and his wife had been privately crowned and anointed in a Catholic rite in their private chapel at the Palace of Whitehall.

********************

Caroline of Ansbach, Queen of Great Britain

- Daughter of Johann Friedrich, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach and his second wife Princess Eleonore Erdmuthe of Saxe-Eisenach

- Born: March 11, 1683, at the Residenz Ansbach in Ansbach, Margraviate of Brandenburg-Ansbach, now in Bavaria, Germany

- Husband: King George II of Great Britain

- Coronation: October 11, 1727 at Westminster Abbey, crowned with her husband

- Crowned by: William Wake, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: November 20, 1737

- Unofficial Royalty: Caroline of Ansbach, Queen of Great Britain

Queen Caroline’s dress was so encrusted with jewels that a pulley had to be devised to lift the skirt so she could kneel down at various points in the ceremony

The composer George Frederick Handel was commissioned to write four new anthems for the coronation, including the rousing Zadok the Priest which has been played at every British coronation ever since. See a performance at this link: YouTube: Zadok the Priest.

********************

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen of the United Kingdom

Charlotte is the second longest-serving consort in British history. Only her descendant, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, husband of another of her descendants, Queen Elizabeth II, served as a consort longer.

Exactly two weeks after their wedding, King George III and Queen Charlotte were crowned at Westminster Abbey. They were carried from St. James’s Palace to Westminster Hall in sedan chairs. At 11:00 AM, they walked the short distance from Westminster Hall to Westminster Abbey. The coronation ceremony was so long that they were not crowned until 3:30 PM. The traditional coronation banquet followed at Westminster Hall. Read about their coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of George III and Charlotte.

********************

Caroline of Brunswick, Queen of the United Kingdom

George IV and his wife Caroline both found each other equally unattractive and never lived together nor appeared in public together. Caroline was increasingly unhappy with her situation and treatment and negotiated a deal with the Foreign Secretary to allow her to leave the country in exchange for a very generous annual allowance. When King George III died in January of 1820, Caroline was determined to return to England and assert her rights as queen. On her way back to England, she received a proposal from her husband offering her an even more generous annual allowance if she would continue to live outside of England. Caroline rejected the proposal and received a royal salute of 21 guns from Dover Castle when she set foot again in England.

George IV was determined to be rid of Caroline and his government introduced a bill in Parliament, the Pains and Penalties Bill 1820, to strip Caroline of the title of queen consort and dissolve her marriage. The reading of the bill in Parliament was effectively a trial of Caroline. On November 10, 1820, a final reading of the bill took place, and the bill passed by 108–99. Prime Minister Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool then declared that since the vote was so close, and public tensions so high, the government was withdrawing the bill.

King George IV’s coronation was set for July 19, 1821, but no plans had been made for Caroline to participate. On the day of the coronation, Caroline went to Westminster Abbey, was barred at every entrance, and finally left. Three weeks later on August 7, 1821, Caroline died at the age of 53, most likely from a bowel obstruction or cancer.

********************

Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, Queen of the United Kingdom

In contrast to his extravagant brother King George IV, King William IV was unassuming and discouraged pomp and ceremony. On the day of his coronation, the doors of Westminster Abbey opened at 4:00 AM. The coronation procession left St. James Palace at 10:15 AM with King William IV dressed in an admiral’s uniform and Queen Adelaide in a white and gold dress. They arrived at Westminster Abbey at 11:00 AM and the coronation ended at 3:00 PM. There was no usual coronation banquet because King William IV decided it was too expensive. Read about the coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of William IV and Adelaide.

********************

Alexandra of Denmark, Queen of the United Kingdom

June 26, 1902 was the date set for the coronation of King Edward VII and his wife Queen Alexandra. However, Edward VII developed appendicitis several days before and then developed peritonitis. Unless he postponed the coronation and immediately had surgery, he would die. Edward VII finally agreed and a new coronation date was set, August 9, 1902. Read more at Unofficial Royalty: Guts and Glory: Edward VII’s Appendix and the Coronation that Never Was.

By August 9, 1902, King Edward VII had recovered and the coronation proceeded as planned. Because of the postponement, many foreign delegations had left London and did not return in August, leaving their countries to be represented by their ambassadors. The 81-year-old Frederick Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury, who died four months later, was almost blind and refused to delegate any part of his duties. He had the prayers printed in large letters on cards so he could see them. He still misread some of the prayers and at the moment of the crowning, after he appeared to almost drop the crown, he placed it on Edward VII’s head backward. Read more about the coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of Edward VII and Alexandra.

********************

Victoria Mary of Teck, Queen Mary of the United Kingdom

This was the first coronation where photography was permitted in Westminster Abbey. Sir John Benjamin Stone was the official photographer. King George V and Queen Mary presented new hangings for the High Altar at Westminster Abbey which are still in use. The hanging is made of cream-white damask silk with an embroidered Crucifixion scene in the center flanked by angels holding shields with the Royal arms and coat of arms of St. Edward the Confessor. Read more at the links below.

********************

Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, Queen Elizabeth of the United Kingdom

George VI’s mother Queen Mary attended the coronation, the first British dowager queen to attend a coronation. Also in attendance were the king and queen’s daughters, 11-year-old Princess Elizabeth and 7-year-old Princess Margaret, who watched the coronation from the Royal Gallery, between their grandmother Queen Mary and their paternal aunt Mary, Princess Royal, Countess of Harewood.

There were some mishaps did occur during the service. Cosmo Gordon Lang, Archbishop of Canterbury thought he had been handed St. Edward’s Crown backward, a bishop stepped on King George V’s train, and another bishop put his thumb over the words of the oath when the King was about to read it.

Read more at the links below.

********************

Queen Camilla of the United Kingdom

To prepare for the coronation, Westminster Abbey was closed to visitors and worshippers from April 25, 2023 and will re-open on Monday, May 8, 2023.

********************

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Note: Many biography articles at Unofficial Royalty and Wikipedia royal biography articles were used to research this article besides the works cited below.

Works Cited

- A Guide to Coronations (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/a-guide-to-coronations (Accessed: March 28, 2023).

- A History of Coronations (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/a-history-of-coronations (Accessed: March 28, 2023).

- Coronation Chair (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/spotlight-on-coronations/coronation-chair (Accessed: March 28, 2023).

- Coronation Theatre (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/spotlight-on-coronations/coronation-theatre (Accessed: March 28, 2023).

- Coronations of Queens Consort at Westminster Abbey (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/queens-consort-of-westminster-abbey?fbclid=IwAR3TVZFaXVje_yK50P2ChvoZdBp8XCpCLNF-t-jA7vr4j1PQEwB8b5ZxGy4 (Accessed: March 28, 2023).

- England and Scotland Monarch Coronations and Other Related British Royal Information (2022) Coronation of British Kings & Queens. Available at: http://kingscoronation.com/ (Accessed: March 28, 2023).

- Flantzer, Susan. (2019) Coronations after the Norman Conquest (1066 – present), Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/coronations-after-the-norman-conquest-1066-present/ (Accessed: March 28, 2023).

- Keay, Anna. (2012) The Crown Jewels. London: Thames and Hudson, Historic Royal Palace.

- Order of Service (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/spotlight-on-coronations/order-of-service (Accessed: March 28, 2023).

- Strong, Roy. (2005, 2022) Coronation – A History of the British Monarchy. London: William Collins.