by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

David Riccio; Credit – Wikipedia

Favorite: a person treated with special or undue favor by a king, queen, or another royal person

David Riccio was an Italian musician and private secretary of Mary, Queen of Scots, and was brutally murdered in the presence of the queen by a conspiracy of Protestant nobles, in part due to the jealousy of Mary’s husband Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. His name is sometimes spelled Rizzio but Riccio is the original Italian spelling. Riccio’s name in Italian records is David Riccio di Pancalieri, David Riccio of Pancalieri. Pancalieri, a town near Turin, then in the Duchy of Savoy, now in the Piedmont section of Italy, was probably where he was born around 1533. He was a descendant of a noble family still living in Piedmont, the Riccio Counts di San Paolo e Solbrito.

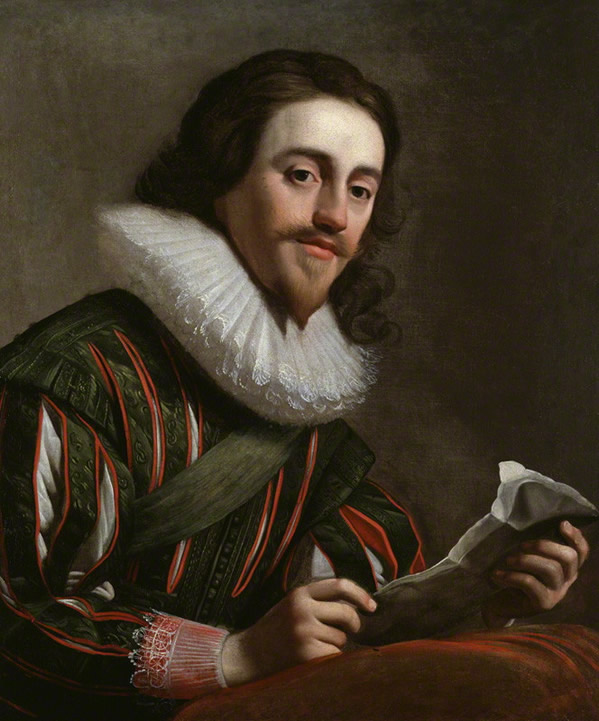

Riccio was a musician at the court of Emanuele Filiberto, Duke of Savoy. He went to Scotland in 1561 with Carlo Ubertino Solaro di Moretta who was sent there as an ambassador by Emanuele Filiberto, Duke of Savoy. Once in Scotland, Riccio made friends with some musicians of Mary, Queen of Scots who told him that Mary needed a bass to complete a vocal quartet, and thus Riccio was introduced to the Scots court. He was considered a very ugly-looking man, but his qualities as a musician and singer caught the queen’s attention. Riccio was a good conversationalist and Mary enjoyed his discussions about continental Europe where she spent her childhood in the French court.

In 1564, Mary chose Riccio to replace Augustine Raulet, her confidential secretary and decipherer, the only person apart from Mary to have the keys to the box containing her personal papers. The reasons for Mary’s decision remain unclear, but soon unfounded rumors were flying that Riccio was a papal spy whose real role was to support Mary in her attempt to subvert the Reformation in Scotland.

Mary, Queen of Scots and her second husband and first cousin Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley; Credit – Wikipedia

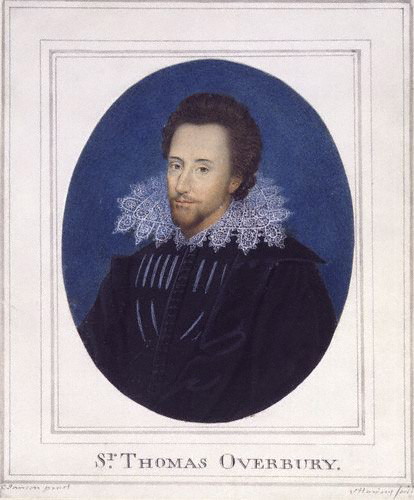

Mary had been married as a teenager to another teenager, François II, King of France. After only a 17-month reign, 16-year-old François died, and Mary returned to Scotland. She needed an heir, so a second marriage became necessary. After considering Carlos, Prince of Asturias, known as Don Carlos, eldest son and heir of King Philip II of Spain, and Queen Elizabeth I’s candidate Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, Mary became infatuated with her first cousin Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. Mary and Darnley were both grandchildren of Margaret Tudor, daughter of King Henry VII of England and sister of King Henry VIII of England. Mary was the daughter of James V, King of Scots, the son of Margaret Tudor and her first husband James IV, King of Scots. Darnley was the son of Lady Margaret Douglas, Margaret Tudor’s only child from her second marriage to Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus. Mary and Darnley married at Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh, Scotland on July 29, 1565.

The marriage angered Queen Elizabeth I of England, who felt that Darnley, as her first cousin once removed and an English subject, needed her permission to marry. Mary’s Protestant illegitimate half-brother James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray was also angered by his sister’s marriage to a prominent Catholic. Mary soon became disillusioned by Darnley’s uncouth behavior and insistence on receiving the Crown Matrimonial which would have made him co-sovereign of Scotland. Mary refused and their relationship became strained. In the autumn of 1565, Mary became pregnant. Darnley was jealous of Mary’s friendship with her private secretary David Riccio, rumored to be the father of her child, and at Darnley’s behest, some Protestant nobles formed a conspiracy to do away with Riccio.

The Protestant nobles were careful to get Darnley’s signature on the conspiracy bond so that he would be as implicated as they would be. The goals mentioned on the bond were obtaining the Crown Matrimonial for Darnley, upholding the Protestant religion, and returning those exiled because of their Protestant religion. In the conspiracy bond, there was no specific mention of any violence toward Riccio, except this rather open-ended statement: “So shall they not spare life or limb in setting forward all that may bend to the advancement of his [Darnley’s] honour.”

Along with Mary’s illegitimate half-brother James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, the nobles who signed the conspiracy pact were:

- Robert Boyd, 5th Lord Boyd

- Archibald Campbell, 5th Earl of Argyll

- Alexander Cunningham, 5th Earl of Glencairn

- James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton

- George Douglas the Postulate, illegitimate brother of James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton

- Andrew Leslie, 5th Earl of Rothes

- Patrick Lindsay, 6th Lord Lindsay of the Byres

- Patrick Ruthven, 3rd Lord Ruthven

- Andrew Stewart, 2nd Lord Ochiltree

Bedchamber of Mary, Queen of Scots; Credit – Royal Collection Trust

On the evening of March 9, 1566, Mary, who was six months pregnant, was in her tiny Supper Room at Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh, Scotland with David Riccio, Mary’s illegitimate half-sister born Lady Jean Stewart, married to Archibald Campbell, 5th Earl of Argyll (one of the conspirators), and Jean’s mother Elizabeth Bethune, married to John Stewart, 4th Lord Innermeath. Mary’s chambers consisted of four rooms: the Outer Chamber where she received visitors, her Bedchamber, a Dressing Room, and the Supper Room entered via a doorway in the Bedchamber. This writer has visited Holyrood Palace and can attest that the Supper Room is indeed tiny – twelve feet square in area. The entrance to the Supper Room can be seen in the above photo taken from the Bedchamber, through open the tapestry, the room with the chair. Directly beneath Mary’s apartments were Darnley’s apartments. The apartments were connected by a narrow privy staircase that had an entrance in Mary’s Bedchamber close to the entrance of the Supper Room.

Supper Room, Mary, Queen of Scots Chambers; Credit – Royal Collection Trust

As supper was being served, Darnley suddenly appeared from the privy staircase. After a few minutes, Patrick Ruthven, 3rd Lord Ruthven also appeared from the privy staircase wearing a helmet and armor. Mary and her supper companions were so astounded by Ruthven with his armor that they thought he must have been ill with a fever and that in his delirium, he thought he was being attacked. However, Mary and those present were more shocked when Ruthven said, “Let it please Your Majesty that yonder man David come forth from your privy-chamber where he hath been overlong.” Mary said that Riccio was there by her royal wish and asked if Ruthven had taken leave of his senses. Ruthven then delivered a long denunciation of Mary’s supposed illicit relationship with Riccio. At the same time, Riccio, becoming more fearful, moved toward a large window in the Supper Room.

The Murder of David Rizzio by William Allan, 1833; Credit – Wikipedia

Ruthven then yelled, “Lay not hands on me, for I will not be handled” which was the signal for the other conspirators to enter the Supper Room from the privy staircase. In the confusion, the table was knocked over. Riccio was clinging to Mary’s skirts while the attackers produced pistols and knives. Riccio’s fingers were pried from Mary’s skirts and he was dragged, kicking and screaming, out of the Supper Room, through the Bedchamber, and into the Outer Chamber. Riccio screamed in French, “ Justice! Justice! Save my life, Madame, save my life!” In the Outer Chamber, Riccio was stabbed fifty-seven times and then his body was thrown down the winding main staircase and stripped of his clothes and jewels.

Ruins of Holyrood Abbey; Credit – By Kaihsu at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons., GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2777882

Within two hours of his death, David Riccio was buried in the cemetery at Holyrood Abbey. Shortly thereafter, there were reports that Mary ordered Riccio’s remains to be interred in the vault of her father James V, King of Scots at Holyrood Abbey. There were other reports that Riccio was buried in the cemetery of the Protestant Canongate Kirk built in Edinburgh from 1688 – 1691. However, it is unlikely that Riccio was buried at Canongate Kirk, as it would have required the reburial of a Catholic in a Protestant cemetery 120 years after his death. It is more likely that David Riccio rests under an anonymous gravestone in the cemetery at Holyrood Abbey which now lies in ruins.

Immediately after the murder, Mary was able to speak to Darnley and convinced him they were both in danger and needed to escape. They stayed at Dunbar Castle, the home of John Stewart, Commendator of Coldingham, another of Mary’s illegitimate half-siblings, and his wife Jean Hepburn, the sister of James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, later Mary’s third husband. After a brief stay at Dunbar Castle, Mary entered Edinburgh on March 18, 1566, with 3,000 troops and moved into Edinburgh Castle to prepare for the birth of her baby. With the conspirators having fled England, Mary appeared to have won and had Darnley declared innocent of Riccio’s murder on March 21, 1566. On June 19, 1566, Mary gave birth to a son.

Like David Riccio, both Mary, Queen of Scots and Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley died violent deaths. James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, later Mary’s third husband, entered into a conspiracy with Archibald Campbell, 5th Earl of Argyll, his brother-in-law and a Riccio murder conspirator, and George Gordon, 5th Earl of Huntly to rid Mary of her husband Darnley. On February 10, 1567, Darnley was killed when the house he was staying at in Edinburgh was blown up. After being imprisoned in English castles for nineteen years by Queen Elizabeth I, Mary was implicated in the Babington Plot, a plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I and put Mary on the English throne. Mary was convicted of treason, condemned to death, and beheaded on February 8, 1587. Mary and Darnley’s infant son succeeded his mother as James VI, King of Scots when she was forced to abdicate in 1567, and he then succeeded Queen Elizabeth I of England upon her death in 1603 as James I, King of England.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. David Rizzio. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Rizzio> [Accessed 2 January 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2017. Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/henry-stuart-lord-darnley/> [Accessed 2 January 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2016. Mary, Queen Of Scots. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/mary-queen-of-scots/> [Accessed 2 January 2021].

- Fraser, Antonia, 1969. Mary Queen Of Scots. New York: Bantam Dell.

- Royal Collection Trust. 2021. Highlights Of The Palace Of Holyroodhouse. [online] Available at: <https://www.rct.uk/visit/palace-of-holyroodhouse/highlights-of-the-palace-of-holyroodhouse#/> [Accessed 2 January 2021].