by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2018

Peter III, Emperor of All Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

Peter III, Emperor of All Russia (Pyotr Feodorovich) had the shortest reign of all the Romanov rulers – just six months. Originally Karl Peter Ulrich of Holstein-Gottorp, he was born February 21, 1728, at Kiel Castle in Kiel, then in the Duchy of Holstein-Gottorp, now in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. His father was Karl Friedrich, reigning Duke of Holstein-Gottorp. His mother was Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna of Russia, the elder of the two surviving daughters of Peter I (the Great), Emperor of All Russia and his second wife, born Marta Helena Skowrońska, the daughter of an ethnic Polish peasant, renamed Catherine (Ekaterina) Alexeievna, and later the successor to her husband Peter the Great as Catherine I, Empress of All Russia. Peter was his parents’ only child. His mother died at the age of 20, three months after his birth.

Peter’s parents; Credit – Wikipedia

Peter’s father never married again and his son was left in the care of the Holstein household guards who put sergeant’s stripes on Peter’s sleeve and let him drill with them. Peter lacked a serious education and any training in governing. Knowing nothing else but what the guards taught him, Peter became passionate about military drilling. In 1739, Peter’s father died, and at the age of eleven, he became Duke of Holstein-Gottorp.

Peter as Duke of Holstein-Gottorp; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1742, Peter’s life dramatically changed when his unmarried maternal aunt, his mother’s younger sister, Elizabeth, Empress of All Russia, declared him her heir and brought him to St. Petersburg, Russia. His arrival in Russia was of great interest to the nobility who were anxious to see the grandson of Peter the Great. However, Jacob von Stäehlin who had been appointed to be his tutor noted that Peter appeared very pale, weak, and skinny. His aunt Elizabeth had a similar reaction – she was struck by his ignorance, his skinny, sickly appearance, and his unhealthy complexion.

Within weeks of his arrival in St. Petersburg, Peter traveled with Empress Elizabeth to Moscow for her coronation. He was in a specially arranged place of honor near Empress Elizabeth during her coronation at the Assumption Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin on May 6, 1742. After the coronation, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the Preobrazhensky Guards and colonel of the First Life Guards Regiment. Every day, he dressed in the uniform of the Preobrazhensky Guards and received monthly reports regarding the two regiments.

Peter’s Preobrazhensky Guards uniform in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg; Photo Credit – Автор: shakko – собственная работа, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24503046

His tutor Jacob von Stäehlin, who considered Peter capable but lazy, was not having much success with his pupil. It appeared to his tutor that Peter had not been taught anything in Holstein except some French which greatly surprised and concerned Empress Elizabeth. Stäehlin simplified instruction for Peter using books with pictures, mathematical models, and coins and medals when teaching Peter Russian history. Twice a week, Stäehlin read newspapers to Peter and explained the history of European states while showing him their location on a globe. Peter often could not sit still and when he walked back and forth around the room, Stäehlin joined him and attempted to occupy him with a useful conversation. Peter much preferred playing with tin soldiers, hunting, and playing the violin.

Peter’s aunt, Elizabeth, Empress of All Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

Isaak Pavlovich Veselovsky, a diplomat who had taught Elizabeth and Peter’s mother French, was charged with teaching Peter the Russian language. Peter was instructed in the Russian Orthodox religion by Archbishop Simeon Feodorovich Theodorsky. On November 17, 1742, Peter converted from Lutheranism to Russian Orthodoxy, was given the name Peter Feodorovich, the title Grand Duke, and was officially named the heir to the Russian throne.

In 1743, Jacob von Stäehlin had more success with Peter’s education. By the end of the year, Peter knew the main points of Russian history and geography and knew all the Russian rulers from Rurik who ruled in the 800s to Peter the Great. Once at the dinner table, Peter corrected a Russian Field Marshal during a discussion concerning ancient Russian history. Empress Elizabeth cried with joy and on the next day gave orders to officially thank Peter’s tutor Jacob von Stäehlin.

It was important to Empress Elizabeth that Peter marry so that the Romanov dynasty would be continued. Elizabeth arranged for Peter to marry his second cousin, Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst (later Catherine II the Great), daughter of Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst and Johanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp. Sophie converted to Russian Orthodoxy, took the name Ekaterina (Catherine) Alexeievna, and married Peter on August 21, 1745, at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Kazan in St. Petersburg.

Peter and Catherine; Credit – Wikipedia

After their wedding, Peter and Catherine were granted the possession of two palaces, Oranienbaum near St. Petersburg and Lyubertsy near Moscow. Jacob von Stäehlin was dismissed from his duties as tutor and Peter’s education was entrusted to the Russian General, Prince Vassili Anikititch Repnin. Peter was able to influence Repnin to ignore anything educational so that Peter could continuously engage in military games and drilling. Empress Elizabeth was much displeased with this and replaced Repnin with Nikolai Naumovich Choglokov who kept much better, but not complete, control of Peter.

Peter’s palace at Oranienbaum; Photo Credit – Автор: IzoeKriv – собственная работа, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43632478

Peter and Catherine’s marriage was not happy but Catherine gave birth to one son, the future Emperor Paul, and one daughter Anna Petrovna, who died in early childhood. Both children were taken by Empress Elizabeth to her apartments immediately after their births to be raised by her. Peter took Elizabeth Romanovna Vorontsova as his mistress and Catherine had affairs with Sergei Saltykov, Grigory Orlov, Alexander Vasilchikov, Grigory Potemkin, and Stanisław August Poniatowski. Later, Catherine claimed that Peter was not the father of her son and successor Paul, and that they had never consummated their marriage.

Children born during the marriage of Peter and Catherine:

- Paul I, Emperor of All Russia (1754 – 1801), married (1) Wilhelmina Louisa of Hesse-Darmstadt (Natalia Alexeievna), died in childbirth, no issue (2) Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg (Maria Feodorovna), had issue including Emperor Alexander I, Emperor Nicholas I, Anna Pavlovna, Queen of the Netherlands; it is possible that Paul’s father was Sergei Vasilievich Saltykov, if this is true, then all subsequent Romanovs were not genetically Romanovs

- Anna Petrovna (1757 – 1759), died in early childhood, probably the daughter of Stanisław August Poniatowski

- Alexei Grigorievich Bobrinsky (1762 – 1813), son of Grigory Grigoryevich Orlov, Catherine’s lover who helped overthrow her husband Peter III

The future Paul I, Emperor of All Russia as a child; Credit – Wikipedia

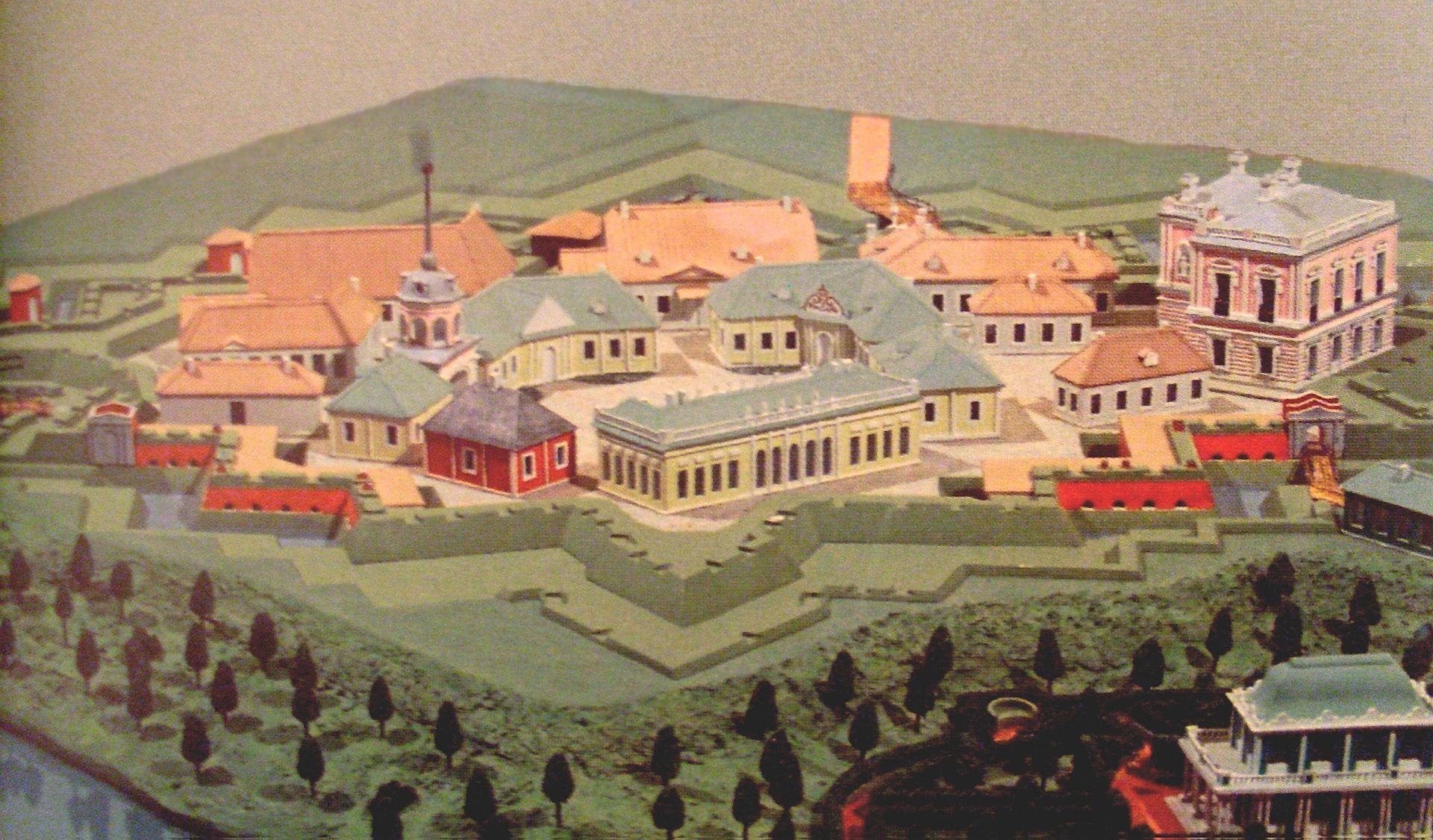

In 1754, General Christian von Brockdorff arrived from Holstein (Peter was still Duke of Holstein-Gottorp) and became the Chamberlain of Peter’s court at Oranienbaum Palace. Brockdorff encouraged Peter’s militaristic habits and his communication with Friedrich II (the Great), King of Prussia. Soon after Brockdorff’s arrival, a detachment of Holstein soldiers arrived. By 1758, the number of Holstein soldiers had risen to about 1,500. Peter and Brockdorff spent most of their time with the Holstein soldiers doing military exercises and maneuvers. Peter had a fortress built for his Holstein troops at Oranienbaum called Peterstadt Fortress.

Peterstadt Fortress, Peter’s pink palace can be seen on the right – Credit – Автор: Chezenatiko – собственная работа, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8319389

Peter never attempted to gain more knowledge about Russia, its people, and its history. He neglected Russian customs, behaved inappropriately during church services, and did not observe fasts and other rites. He spoke Russian poorly and infrequently. Empress Elizabeth did not allow Peter to participate in government affairs. Peter openly criticized the activities of the government, and during the Seven Years’ War publicly expressed sympathy for Friedrich II (the Great), King of Prussia.

Meanwhile, Peter’s wife Catherine became friends with Princess Ekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova-Dashkova, the sister of Peter’s mistress, who introduced Catherine to several powerful political groups that opposed her husband Peter. Peter’s temperament became quite unbearable for those who resided in the palace. Catherine spent much time in her own private boudoir to hide away from Peter’s abrasive personality.

Catherine’s friend, Princess Ekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova-Dashkova; Credit – Wikipedia

Empress Elizabeth was often ill and reluctant to show herself in public because of her ill health. In 1757, she suffered a stroke at a well-attended church service, and then her health situation became well-known. A particularly difficult problem for her was the succession. She was childless and the Romanov dynasty had been extinct in the male line since the death of Peter II in 1730. Elizabeth did not love her nephew Peter and his political views did not suit her because he admired her enemy Friedrich II (the Great), King of Prussia. The sicker Elizabeth became, the more the courtiers turned away from her and tried to please the heir to the throne.

On January 3, 1762, Elizabeth had a massive stroke and the doctors agreed she would not recover. Peter, Catherine, and others close to her gathered around her bed in the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. Elizabeth, alert and clear-headed, showed no signs of wishing to change the succession. She asked Peter to look after little Paul, who she dearly loved. Peter quickly promised to do so, knowing that Elizabeth could change the succession with a single word. On January 5, 1762, Elizabeth, Empress of All Russia died at the age of 52 and her nephew became Peter III, Emperor of All Russia.

Catherine in mourning clothes at the coffin of Elizabeth, Empress of All Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

As the death of Empress Elizabeth was announced to the court, the room was filled with moans and weeping. Peter was unpopular and few were looking forward to his reign. Later that day, when high government officials and military officers gathered to take the oath of allegiance to the new emperor, Peter insisted that they wear bright colorful clothing. After the oath, Peter gave a gala banquet for over a hundred guests. During the religious ceremonies for the lying-in-state of the deceased empress, Peter, according to Princess Dashkova “made faces, acted the buffoon and imitated poor old ladies.” Peter did little to win the support of Empress Elizabeth’s friends and courtiers.

Peter’s foreign policy also did little to win supporters. At the time of Elizabeth’s death, Russia was on the verge of defeating Prussia in the Seven Years’ War. Instead, because Friedrich I (the Great), King of Prussia was his idol, Peter withdrew Russian troops from Berlin and marched against the Austrians, Russia’s ally. As Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, Peter planned war against Denmark to restore parts of Schleswig to his Duchy. This war would bring no benefit to Russia and even the Prussian king advised Peter against taking this action. The Danish war was planned for June but never happened.

The last straw for Peter may have been how he treated the Russian army. Peter abolished “the guard within the guard”, a group within the Preobrazhensky Regiment, created by Empress Elizabeth as her personal guard in remembrance of their support in the coup which brought her to the throne. He replaced “the guard within the guard” with his own Holstein guard and often spoke about their superiority over the Russian army.

Meanwhile, Catherine’s position deteriorated along with the position of three groups – the clergy, senior statesmen, and the Imperial Guard, the Preobrazhensky Regiment. Peter began to think about divorcing Catherine and marrying his mistress. Wisely, Catherine quietly aligned herself with the three groups. She remained calm and dignified even when Peter grossly insulted her in public. The devotion of the Preobrazhensky Regiment to Catherine was never in doubt because her lover Grigory Orlov and his four brothers were all members of the Guard.

Alexei and Grigory Orlov in the 1770s; Credit – Wikipedia

A conspiracy to overthrow Peter was planned and centered around the five Orlov brothers. On July 9, 1762 (June 29 in Old Style, the feast day of St. Peter and Paul), at Peterhof, a celebration of Peter’s name day was planned. It was no coincidence that the conspirators chose this time for their attack. The day before, Peter was to travel from Oranienbaum to Peterhof. The brothers Alexei Orlov and Grigory Orlov made preparations during the weeks before the planned celebration. With threats and bribes of vodka and money, the brothers set up the guards against Peter.

Peter was late leaving Oranienbaum due to a hangover and his daily habit of reviewing his Holstein troops. He was to meet Catherine at Peterhof but she was not there when he arrived. Eventually, Peter and the few advisers he had with him began to suspect what was happening. Peter sent members of his entourage to St. Petersburg to find out what was happening but none returned. Eventually, he learned that Catherine had proclaimed herself Empress and that senior government officials, the clergy, and all the Guards supported her. Peter ordered his Holstein guards to take up defensive positions at Peterhof. They did so but were afraid to tell Peter they had no cannonballs to fire. Peter thought about fleeing but was told no horses were available because his entourage had all arrived in carriages. Learning that Catherine and the Guards were approaching Peterhof, Peter made a desperate decision to sail Kronstadt, a fortress on an island. Upon arrival, Peter was refused admittance because all those in the fortress had sworn allegiance to Catherine. Peter rejected the advice of his advisors to go to the Prussian army and returned to Oranienbaum.

Peter and his Holstein guards were behind the gates at Oranienbaum and Alexei Orlov and his men had surrounded Oranienbaum. Peter sent a message that he would renounce the throne if he, his mistress Elizabeth Romanovna Vorontsova, and his favorite Russian general would be allowed to go to Holstein. Catherine sent Grigori Orlov and a Russian general to Oranienbaum insisting that Peter write a formal announcement of abdication in his own handwriting. Orlov was to deal with the abdication and the general was to lure Peter out of Oranienbaum and back to Peterhof to prevent any bloodshed. Orlov rode back to Peterhof with the signed abdication announcement and the general convinced Peter to go to Peterhof and beg Catherine for mercy. Upon arrival at Peterhof, Peter was arrested and taken by Alexei Orlov to Ropsha, a country estate outside of St. Petersburg.

Catherine had to deal with the same dilemma that Empress Elizabeth had to deal with regarding Ivan VI who she had deposed – keeping a former emperor around was a threat to her throne. Catherine intended to send Peter to Shlisselburg Fortress where Ivan VI had been imprisoned for more than twenty years. However, Catherine did not have to live with a living deposed emperor for long. The true circumstances of Peter’s death at the age of 34 on July 17, 1762, are unclear. It is possible that Peter was murdered by Alexei Orlov. Another story is that Peter had been killed in a drunken brawl with one of his jailers. At the time, the official cause was “an acute attack of colic during one of his frequent bouts with hemorrhoids.” It is doubtful that Catherine played any role in Peter’s death.

On July 19, 1762, Peter was buried without honors in the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in St. Petersburg. In 1796, immediately after the death of Catherine II, on the orders of her son and successor Paul I, Peter’s remains were transferred first to the Grand Church of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia, and then to the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg, the burial site of the Romanovs. 60-year-old Alexei Orlov was made to walk in the funeral cortege, holding the Imperial Crown as he walked in front of the coffin. Peter III was reburied in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg at the same time as the burial of his wife Catherine II. Peter III had never been crowned so at the time of his reburial, Paul I personally performed the ritual of coronation of his father’s remains.

The tombs of Catherine II and Peter III (back row) at the Peter and Paul Cathedral; Photo Credit – Автор: Deror avi – собственная работа, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8368144

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Romanov Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Tsardom of Russia/Russian Empire Index

- Romanov Births, Marriages and Deaths

- Romanov Burial Sites

- Romanovs Killed During the Russian Revolution

- Romanovs Who Survived the Russian Revolution

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. (2018). Peter III. (Russland). [online] Available at: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_III._(Russland) [Accessed 10 Jan. 2018].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Peter III of Russia. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_III_of_Russia [Accessed 10 Jan. 2018].

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1981). The Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias. New York, NY.: Doubleday

- Massie, R. (2016). Catherine the Great. London: Head of Zeus.

- Ru.wikipedia.org. (2018). Пётр III. [online] Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9F%D1%91%D1%82%D1%80_III [Accessed 10 Jan. 2018].