by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

King Louis XVI of France and his wife Queen Marie Antoinette were both beheaded by the guillotine at the Place de la Révolution (now the Place de la Concorde) in Paris, France. Louis XVI was executed on January 21, 1793, and Marie Antoinette was executed on October 16, 1793.

King Louis XVI of France

King Louis XVI of France, circa 1784; Credit – Wikipedia

Born in 1754, King Louis XVI of France was the son of Louis, Dauphin of France (the son of King Louis XV) and Maria Josepha of Saxony. Unfortunately, like several other Dauphins that preceded him, Louis, Dauphin of France died prematurely in 1765, from tuberculosis, and never became King of France. Upon his father’s death, the future Louis XVI became the heir to his grandfather’s throne.

In 1770, King Louis XV allied with Empress Maria Theresa of Austria and soon a marriage was arranged between the two dynasties. Louis XV’s grandson, the future Louis XVI, became engaged to Empress Maria Theresa’s youngest daughter Archduchess Maria Antonia. Fifteen-year-old Louis married fourteen-year-old Maria Antonia in 1770. Maria Antonia took the French version of her name, becoming Marie Antoinette, Dauphine of France.

When his grandfather King Louis XV died in 1774, Louis became King Louis XVI of France. He was just nineteen years old and notably unprepared for his role and faced a growing distrust of the monarchy and a country that was deeply in debt.

- For more information, see Unofficial Royalty: King Louis XVI of France.

**********************

Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria, Queen Marie Antoinette of France

Queen Marie Antoinette of France, 1786; Credit – Wikipedia

Queen Marie Antoinette of France was born Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria, Princess of Hungary and Bohemia in 1755. Maria Antonia’s mother was the powerful Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria and Queen of Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia in her own right. Marie Antoinette’s father, born François Étienne, Duke of Lorraine, became Holy Roman Emperor Franz I, but only with his wife’s help. Maria Teresa was unable to become the sovereign of the Holy Roman Empire because she was female. The Habsburgs had been elected Holy Roman Emperors since 1438, but in 1742, when Maria Theresa’s father died, Holy Roman Emperor Charles VII from the German House of Wittelsbach was elected. When Charles VIII died three years later, Maria Theresa arranged for her husband to be elected Holy Roman Emperor. Despite the snub, Maria Theresa wielded the real power behind the throne.

After she came to France and married the future Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette received a mixed reception. Initially well-liked by the common people, particularly due to her beauty and warm personality, she was distrusted by those who resented France’s contentious relationship with Austria. As Queen, Marie Antoinette was often criticized for her spending, indulging in lavish gowns and other luxuries while the country was suffering a financial crisis. This would contribute to a growing animosity from the French people toward their Queen and the “old guard” within the French court.

Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette had four children but their eldest son died when he was eight and their youngest daughter died in infancy. Louis-Charles, who had become Dauphin of France upon the death of his elder brother, was titular King Louis XVII of France after his father’s execution. He died from tuberculosis at the age of ten, imprisoned at the Temple, the remains of a medieval fortress in Paris, where his family had been imprisoned after their fall from power. Marie Thérèse Charlotte, Louis and Marie Antoinette’s eldest child, survived the French Revolution and married her paternal first cousin Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême.

- For more information, see Unofficial Royalty: Maria Antonia of Austria, Queen Marie Antoinette of France

**********************

The Seeds of Revolution

Storming the Bastille by Jean-Pierre Louis Laurent Houël, 1789; Credit – Wikipedia

King Louis XVI’s attempts at financial reforms angered the French people and contributed to the fall of the monarchy. As he saw his power diminishing, he was forced to convoke the Estates-General for the first time since 1614, to come up with solutions to the dire financial problems of the French government. Divided into three groups called Estates – the clergy (First Estate), the nobility (Second Estate), and the common people (Third Estate), they quickly came to an impasse over how votes would be taken. Eventually, in June 1789, the Third Estate declared itself as the National Assembly and asked the other two to join them, bringing about the outbreak of the French Revolution. Just weeks later, the revolutionaries stormed the Bastille, a medieval armory, fortress, and political prison was a symbol of the monarchy’s abuse of power. Within months, Louis XVI saw the majority of his power handed over to the elected representatives of the French people.

A contemporary illustration of the Women’s March on Versailles, October 5, 1789; Credit – Wikipedia

With growing distrust in the monarchy and a quickly spreading hatred of the Austrian Queen Marie Antoinette, compounded once again by King Louis XVI’s inability or unwillingness to make, and stick to, strong decisions, he soon found that he was losing the support of even the more moderate politicians in the French government. On October 5, 1789, an angry mob of women marched to the Palace of Versailles and gained entry to the palace with plans to kill Queen Marie Antoinette. After the intervention of the Marquis de Lafayette who calmed the crowd, King Louis XVI and his family were brought to the Tuileries Palace in Paris.

The future of the French monarchy looked very bleak. King Louis XVI planned to escape Paris, to Montmédy in northeastern France where he would initiate a counter-revolution by joining with royalist troops. Know as the Flight to Varennes, the plan failed miserably. On June 21, 1791, Louis and his family secretly fled the palace but were captured and arrested the following day. Once again, Louis’s indecisiveness and his misguided belief that his people supported him led to the plan falling apart. Brought back to the Tuileries Palace, the family was placed under heavy security to prevent another chance of escape.

Marie Antoinette, with her son, daughter, and sister-in-law Madame Élisabeth, facing the mob at the Tuileries Palace; Credit – Wikipedia

On July 25, 1792, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick issued the Brunswick Manifesto, stating that he, along with Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor, Marie Antoinette’s brother, and King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia intended to restore King Louis XVI to his full power and would support this effort by any force necessary. The manifesto proved to be more harmful than helpful. To many, this reinforced their belief that King Louis XVI was conspiring against his own country. Within weeks, the people revolted, storming the Tuileries Palace and forcing the royal family to take refuge in the Legislative Assembly building on August 10, 1792.

**********************

The Trial of King Louis XVI

The Examination of Louis the Last; Credit – Wikipedia

Louis was arrested on August 11, 1792, and was imprisoned with his family at the Temple, the remains of a medieval fortress in Paris. On September 21, 1792, the National Assembly declared France a Republic, abolishing the monarchy, and stripping Louis and his family of all their titles and honors. The former King of France was now known as Citizen Louis Capet.

Louis’ trial before the National Convention commenced on December 3, 1792, and the next day, Jean-Baptiste Mailhe, the National Convention’s secretary, also a deputy, read: “Louis, the French Nation accuses you of having committed a multitude of crimes to establish your tyranny, in destroying her freedom.” Louis, sitting in an armchair, then heard Mailhe read the thirty-three charges.

Louis was allowed a defense which his defense team eloquently presented. Raymond Desèze, the lead counsel, ended the defense with: “Louis ascended the throne at the age of twenty, and at the age of twenty, he gave to the throne the example of character. He brought to the throne no wicked weaknesses, no corrupting passions. He was economical, just, severe. He showed himself always the constant friend of the people. The people wanted the abolition of servitude. He began by abolishing it on his own lands. The people asked for reforms in the criminal law… he carried out these reforms. The people wanted liberty: he gave it to them. The people themselves came before him in his sacrifices. Nevertheless, it is in the name of these very people that one today demands… Citizens, I cannot finish… I stop myself before History. Think how it will judge your judgment, and that the judgment of him will be judged by the centuries.”

Louis then made a statement in his defense: “You have heard my defense, I would not repeat the details. In talking to you perhaps for the last time, I declare that my conscience reproaches me with nothing, and my defenders have told you the truth. I never feared the public examination of my conduct, but my heart is torn by the imputation that I would want to shed the blood of the people and especially that the misfortunes of August 10th be attributed to me. I avow that the many proofs that I have always acted from my love of the people, and the manner in which I have always conducted myself, seemed to prove that I did not fear to put myself forward in order to spare their blood, and forever prevent such an imputation.”

On January 17, 1793, 693 deputies of the National Convention voted “Yes” in favor of a guilty verdict. No deputies voted “No” but twenty-six deputies attached some condition to their votes. Twenty-six deputies were not present for the vote, most away on official business. Twenty-three deputies abstained, for various reasons. Several abstained because they felt they had been elected to make laws and not to judge.

When Louis’ punishment came to a vote, 721 deputies were present for the vote. 34 voted for death with attached conditions, 2 voted for life imprisonment in irons, 319 voted for imprisonment until the end of the war, to be followed by exile, 361 voted for death without conditions. The punishment of death was carried by a mere five votes.

**********************

The Execution of King Louis XVI

Execution of Louis XVI; Credit – Wikipedia

In Paris, the guillotine was located at the Place de la Révolution (now the Place de la Concorde), located between the Champs-Elysées to the west and the Tuileries Garden to the east in Paris, France. Louis XVI was executed on January 21, 1793. The night before the execution Louis’ family, his wife Marie Antoinette, his daughter Marie Thérèse Charlotte, his son Louis-Charles, and his sister Madame Élisabeth (who would be guillotined in May 1794), were allowed into his room to say their farewells. Louis only got them to leave with a promise to see them early the next morning. However, on the advice of his confessor, Louis refrained from seeing his family on the morning of his execution.

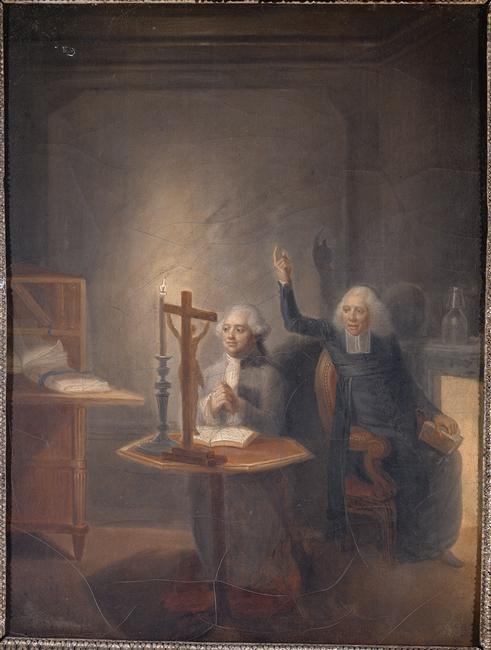

Father Edgeworth de Firmont heard Louis’ last confession by Jean Jacques Hauer; Credit – Wikipedia

Louis XVI was awakened at 5:00 AM by his valet who helped him dress. Louis’ last confessor was Henry Essex Edgeworth, an Irish Catholic priest also known as L’Abbé Edgeworth de Firmont, who was the confessor of Louis’ sister Élisabeth. Around 6:00 AM, Father Edgeworth de Firmont celebrated Louis’ last mass and gave Louis the Last Rites, and then he accompanied Louis to the scaffold.

A 9:00 AM, a green carriage left the Temple transporting Louis, Father Edgeworth de Firmont, and two militiamen to the place of execution. General Antoine Joseph Santerre, who had been responsible for Louis during his imprisonment, conducted Louis to his execution along with 200 mounted police. The route to the site of the execution was lined with 80,000 soldiers. The procession reached the Place de la Révolution around 10:00 AM.

Louis XVI and his confessor Father Edgeworth de Firmont approach the scaffold; Credit – Wikipedia

Louis was met by the executioner Charles-Henri Sanson who conducted him to the foot of the scaffold. Sanson asked Louis to remove his frock coat and his neckerchief, and to open the collar of his shirt. Louis initially refused to have his hands tied but Father Edgeworth de Firmont convinced him and Sanson agreed to use Louis’ handkerchief instead of a rope. One of Sanson’s assistants cut Louis’ collar and his hair. Accompanied by drum rolls, Louis, assisted by Father Edgeworth de Firmont climbed the scaffold stairs and joined Sanson and his four assistants on the scaffold.

Execution of Louis XVI in the Place de la Révolution; Credit – Wikipedia

Louis gestured to the drums to stop and said, “My people, I die innocent!” Then, turning towards his executioners, Louis said “Gentlemen, I am innocent of everything of which I am accused. I hope that my blood may cement the good fortune of the French.” Louis wanted to say more but General Santerre ordered the drumroll to resume to drown out Louis’ voice. Louis was then strapped down to the bench under the guillotine and at 10:22 AM, the executioner Charles-Henri Sanson let the guillotine blade fall. One of Sanson’s assistants lifted Louis’ head. Those who had gathered shouted, “Vive la Nation! Vive la République!”

Louis’ body was taken immediately to the nearby Cimetière de la Madeleine that served as the cemetery for 1343 people who had been guillotined from 1792 to 1794. At the cemetery, a short funeral service was held and Louis’ remains were thrown in a deeper pit than usual to avoid desecration of the grave, covered in quicklime, and buried with dirt.

**********************

What happened to Queen Marie Antoinette?

Marie Antoinette while a prisoner at The Temple, painted by Alexandre Kucharski circa1792: Credit – Wikipedia

After the execution of Louis XVI, the fate of Marie Antoinette and her children was the source of much debate in the National Convention. While some argued Marie Antoinette should be put to death, others suggested holding her for ransom from the Holy Roman Empire, exchanging her for French prisoners of war, or exiling her to America. On July 3, 1793, her son Louis-Charles was forcibly taken from her, with the intent of turning him against his mother. On August 1, 1793, Marie Antoinette was taken from the Temple and placed in a small cell in the Conciergerie, part of the former royal palace, the Palais de la Cité, where thousands of prisoners were held and tried during the French Revolution. The once Queen of France was now known as Prisoner Number 280.

Trial of Marie-Antoinette on October 15, 1793 by Pierre Bouillon, 1793; Credit – Wikipedia

On October 14, 1793, Marie Antoinette was tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal at the Conciergerie. Among other charges, she was accused of organizing orgies at the Palace of Versailles, sending millions in French treasury money to Austria, planning the massacre of the National Guards, and incest with her son. Before his mother’s trial, Louis-Charles was forced to sign a statement that his mother had committed incest with him. On October 16, 1793, at 4:30 AM, Marie Antoinette was found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death.

Marie Antoinette’s cell in the Conciergerie where she was allowed no privacy; Credit – By André Lage Freitas Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17078785

Less than four hours later, the four judges and the clerk of the Revolutionary Tribunal entered Marie Antoinette’s cell and read her sentence for the second time. She was forced to change into a plain white dress, white being the color worn by widowed queens of France, in front of the men gathered in her cell. The executioner Henri Sanson, the son of her husband’s executioner, cut her hair, bound her hands, and put her on a rope leash.

Marie Antoinette in the cart, ignoring Father Girard with executioner Henri Sanson, standing behind Marie Antoinette by Henri Jean-Baptiste Victoire Fradelle; Credit – Wikipedia

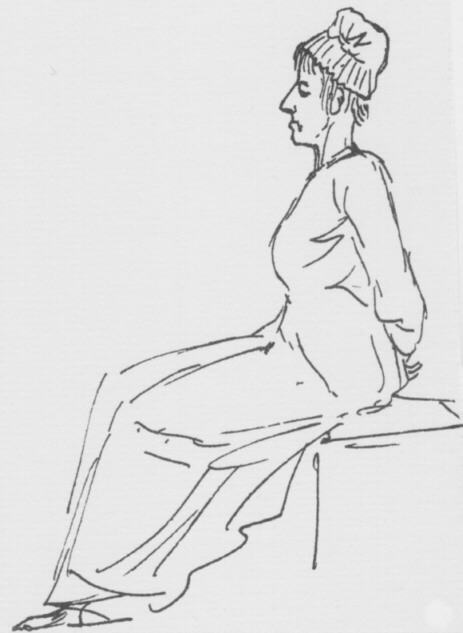

Unlike her husband, who had been taken to his execution in a carriage Marie Antoinette had to sit in an open wooden cart. Father Girard, the parish priest of Saint-Landry Church, was appointed to accompany her as her confessor. However, since she did not have the choice of her own priest, as her husband did, Marie Antoinette ignored Father Girard all the way to the scaffold. The executioner Henri Sanson stood behind the former queen and his assistant sat at the back of the cart. 30,000 troops stood along the route to the place of execution. During the hour-long ride, Marie Antoinette was subjected to verbal insults from the crowds along the route. The painter Jacques-Louis David observed the procession and drew a sketch that has become legendary.

Marie Antoinette on the way to the scaffold by Jacques-Louis David, 1793; Credit – Wikipedia

The cart carrying Marie Antoinette arrived at the Place de la Révolution around noon. Although her hands were tied, she exited the cart and climbed the scaffold steps without help. While climbing up the steps, she lost one of her shoes. The shoe is part of the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen in Caen, France. As she walked to the guillotine, Marie Antoinette stepped on the executioner’s foot. She said to him, “Sir, I beg your pardon, I did not do it on purpose,” her last words. She was tied to the bench under the guillotine and at 12:15 PM, Henri Sanson let the blade of the guillotine fall. He then grabbed Marie-Antoinette’s head by the hair and showed it to the people, shouting “Vive la République!”

Marie Antoinette’s execution in 1793 at the Place de la Révolution; Credit – Wikipedia

Marie Antoinette’s remains were taken to the Cimetière de la Madeleine, where her husband had been buried, thrown into a mass grave, and covered with quicklime.

**********************

Aftermath

The French Royal Family in 1823 – left to right: Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte, Duchess of Angoulême; Louis-Antoine, Duke of Angoulême; Prince Henri de Bourbon; Charles-Philippe, Count of Artois; King Louis XVIII of France; Princess Louise-Marie-Thérèse d’Artois; Marie-Caroline, Duchess of Berry; Credit – Wikipedia

The Bourbons were restored to the throne of France in the aftermath of Napoléon I’s defeat and final exile. Two of King Louis XVI’s brothers, King Louis XVIII and King Charles X, reigned from 1815 – 1830. The Bourbon Restoration lasted until 1830, when during the July Revolution of 1830, the House of Bourbon was overthrown by Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, a descendant of King Louis XIV’s brother Philippe I, Duke of Orleans, who reigned as Louis-Philippe I, King of the French until he was overthrown in 1848. Napoleon III, Emperor of the French, was the last monarch of France, reigning from 1852 until 1870. He was the nephew of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French and the grandson of Napoleon’s first wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais and her first husband Alexandre de Beauharnais.

Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette’s only surviving child Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte married her first cousin Louis Antoine of France, Duke of Angoulême, the eldest son of Louis XVI’s brother, King Charles X. Father Edgeworth de Firmont, who had accompanied King Louis XVI to his execution, performed their marriage ceremony. Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte and Louis Antoine’s marriage was childless.

Grave of King Louis XVI at the Basilica of Saint-Denis; Credit – www.findagrave.com

Grave of Marie Antoinette at the Basilica of Saint-Denis; Credit – www.findagrave.com

One of the first things King Louis XVIII, a younger brother of the guillotined King Louis XVI, did after the Bourbon Restoration was to order a search for the remains of his brother and sister-in-law, King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette. The few remains that were found at the Cimetière de la Madeleine were reburied at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, the traditional burial site of the French royals, on January 21, 1815, the twenty-second anniversary of Louis XVI’s execution. A memorial to Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, sculptured by Edme Gaulle and Pierre Petitot, was placed in the Basilica of Saint-Denis.

Memorial to Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette by Edme Gaulle and Pierre Petitot, 1830; Credit – By Eric Pouhier – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1765224

Between 1816 and 1826, the Chapelle Expiatoire, dedicated to the memory of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, was built at the site of the former Cimetière de la Madeleine in Paris. King Louis XVIII and Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte, Duchess of Angoulême shared the expense of building the Chapelle Expiatoire.

A Mass in the Chapelle Expiatoire by Lancelot Théodore Turpin de Crissé, 1835; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Cronin, Vincent. (1974). Louis and Antoinette. New York: William Morrow & Company, Inc.

- En.wikipedia.org. (2020). Chapelle expiatoire. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chapelle_expiatoire [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2020). Execution of Louis XVI. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Execution_of_Louis_XVI [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2020). Louis XVI of France. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_XVI_of_France [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2020). Marie Antoinette. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_Antoinette_of_Austria [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2020). Trial of Louis XVI. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trial_of_Louis_XVI [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. (2020). Exécution de Louis XVI. [online] Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ex%C3%A9cution_de_Louis_XVI [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. (2020). Exécution de Marie-Antoinette d’Autriche. [online] Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ex%C3%A9cution_de_Marie-Antoinette_d%27Autriche [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. (2020). Marie-Antoinette d’Autriche. [online] Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie-Antoinette_d%27Autriche [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. (2020). Procès de Marie-Antoinette. [online] Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proc%C3%A8s_de_Marie-Antoinette [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- Fraser, Antonia. (2001). Marie Antoinette: The Journey. New York: Doubleday.

- Mehl, Scott. (2016). King Louis XVI of France. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-louis-xvi-of-france/ [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- Mehl, Scott. (2016). Maria Antonia of Austria, Queen of France (Marie Antoinette). [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/maria-antonia-of-austria-queen-of-france-marie-antoinette/ [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].