by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2025

The Hawaiian Islands, located in the Pacific Ocean, were originally divided into several independent chiefdoms. The Kingdom of Hawaii was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great of the independent island of Hawaii, conquered the independent islands of Oahu, Maui, Molokai, and Lanai, and unified them under one government and ruled as Kamehameha I, King of the Hawaiian Islands. In 1810, the whole Hawaiian archipelago became unified when Kauai and Niihau voluntarily joined the Kingdom of Hawaii. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom: the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

In 1778, British explorer James Cook visited the islands. This led to increased trade and the introduction of new technologies and ideas. In the mid-19th century, American influence in Hawaii dramatically increased when American merchants, missionaries, and settlers arrived on the islands. Protestant missionaries converted most of the native people to Christianity. Merchants set up sugar plantations and the United States Navy established a base at Pearl Harbor. The newcomers brought diseases that were new to the indigenous people including influenza, measles, smallpox, syphilis, tuberculosis, and whooping cough. At the time of James Cook’s arrival in 1778, the indigenous Hawaiian population is estimated to have been between 250,000 and 800,000. By 1890, the indigenous Hawaiian population declined had to less than 40,000.

In 1893, a group of local businessmen and politicians composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national overthrew Queen Liliuokalani, her cabinet, and her marshal, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii. This led to the 1898 annexation of Hawaii as a United States territory. On August 21, 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state of the United States.

In 1993, one hundred years after the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown, the United States Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Apology Resolution which “acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and further acknowledges that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaii or through a plebiscite or referendum”. As a result, the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom in Hawaii, was established along with ongoing efforts to redress the indigenous Hawaiian population.

********************

Kalākaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands; Credit – Wikipedia

Known for his patronage and the restoration of many Hawaiian cultural traditions, Kalākaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands from 1874 – 1891 was the first of the two monarchs of the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands from the House of Kalākaua. He was born David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Māhinulani Nālaʻiaʻehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua on November 16, 1836, in the grass hut compound of his maternal grandfather at the base of Punchbowl Crater in Honolulu, Kingdom of Hawaii now in the state of Hawaii. Known as David, he was the second eldest of the seven surviving children who survived infancy and the second of the three surviving sons of first cousins Caesar Kaluaiku Kamakaʻehukai Kahana Keola Kapaʻakea and Analea Keohokālole.

David’s family was aliʻi nui, Hawaiian nobility, and were distantly related to the reigning House of Kamehameha, sharing common descent from Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku, King of the island of Hawaii and the great-grandfather of Kamehameha I, the first King of the Kingdom of Hawaii. His father Caesar Kapaʻakea was a Hawaiian chief who served in the House of Nobles from 1845 until he died in 1866 and on the King’s Privy Council from 1846 – 1866. David’s mother Analea Keohokālole, who was of a higher rank than her husband, was a Hawaiian chiefess and a member of the House of Nobles from 1841 to 1847, and on the King’s Privy Council 1846 to 1847.

David had six siblings who survived infancy:

- James Kaliokalani (1835 – 1852), died in his teens

- Queen Lydia Liliʻuokalani (1838 – 1917), the only queen regnant and the last monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaii, married John Owen Dominis, no children

- Anna Kaʻiulani (1842 – ?)

- Kaʻiminaʻauao (1845 – 1848), died from measles during an epidemic of measles, whooping cough, and influenza that killed more than 10,000 Native Hawaiians

- Miriam Likelike (1851 – 1887), married Archibald Scott Cleghorn, Scottish businessman, had one daughter Princess Kaʻiulani, the last heir to the throne before the 1893 overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii

- William Pitt Leleiohoku II (1855 – 1877), unmarried, died from rheumatic fever

David, aged fourteen; Credit – Wikipedia

David was declared eligible to be in the line of succession by the royal decree of King Kamehameha III and therefore attended the Chiefs’ Children’s School, later known as Royal School, in Honolulu, which is still in existence as a public elementary school, the Royal Elementary School, the oldest school on the island of Oahu. His classmates included the other children declared eligible to be in the line of succession including his siblings James Kaliokalani and the future Queen Lydia Liliʻuokalani, and their thirteen royal relations including the future kings Kamehameha IV, Kamehameha V, and Lunalilo. Following his formal schooling, David studied law under Charles Coffin Harris, a New England lawyer who became a politician and judge in the Kingdom of Hawaii. David would appoint Harris as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Hawaii in 1877. David held various military, government, and court positions that provided him with much experience for his future role as King of the Hawaiian Islands.

David’s wife Queen Kapiʻolani; Credit – Wikipedia

On December 19, 1863, David married Kapiʻolani Napelakapuokakaʻe, the daughter of High Chief Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole of Hilo and High Chiefess Kinoiki Kekaulike of Kauaʻi, the daughter of King Kaumualiʻi, the last king of an independent Kauaʻi. Kapiʻolani was the widow of High Chief Bennett Nāmākēhā, the uncle of King Kamehameha IV’s wife Queen Emma, and served as Queen Emma’s lady-in-waiting, and Prince Albert Edward Kamehameha‘s nurse and caretaker, the only child of King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma who died when he was four years old. David and Kapiʻolani’s marriage was childless.

On February 3, 1874, Lunalilo, King of the Hawaiian Islands (born William Charles Lunalilo) died from tuberculosis at the age of 39 without naming an heir. As King Lunalilo had wanted to make Hawaii more democratic, it is thought that he wished to have the people choose their next ruler. The Legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the people’s representatives, would choose the next monarch from the eligible royal family members. Queen Emma, the widow of King Kamehameha IV, claimed that King Lunalilo had wanted her to succeed him, but he died before a formal proclamation could be made. She decided to run in the election against David who had lost to King Lunalilo in a similar election in 1873. While the Hawaiian people supported Emma, it was the legislature that elected the new monarch. They favored David who won the election 39 – 6. David reigned as King Kalākaua and became the first of two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaiian Islands from the House of Kalākaua, who were also the last two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Upon his accession to the throne, David named his brother William Pitt Leleiohoku II as his heir apparent. When his brother died from rheumatic fever in 1877, David changed the name of his sister Lydia Dominis to Liliuokalani and named her as his heir apparent. She acted as regent during her brother’s absences from the country, and after his death, she became the last monarch of Hawaii.

During David’s reign, the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, a free trade agreement between the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands and the United States greatly benefitted Hawaii. The treaty gave free access to the United States market for sugar and other products grown in the Kingdom of Hawaii. In return, Hawaii guaranteed the United States that it would not cede or lease any of its land to other foreign powers. The treaty led to large investment by Americans in sugarcane plantations in Hawaii. At a later time, an additional clause was added to the treaty allowing the United States exclusive use of land in the area known as Puʻu Loa, which was later used for the American Pearl Harbor naval base. David’s extravagant expenditures and his plans for a Polynesian confederation gave power to the annexationists who were already working toward a United States takeover of Hawaii, which would happen during the reign of David’s sister Queen Liliuokalani. In 1887, David was pressured to sign a new constitution that made the monarchy little more than a figurehead position.

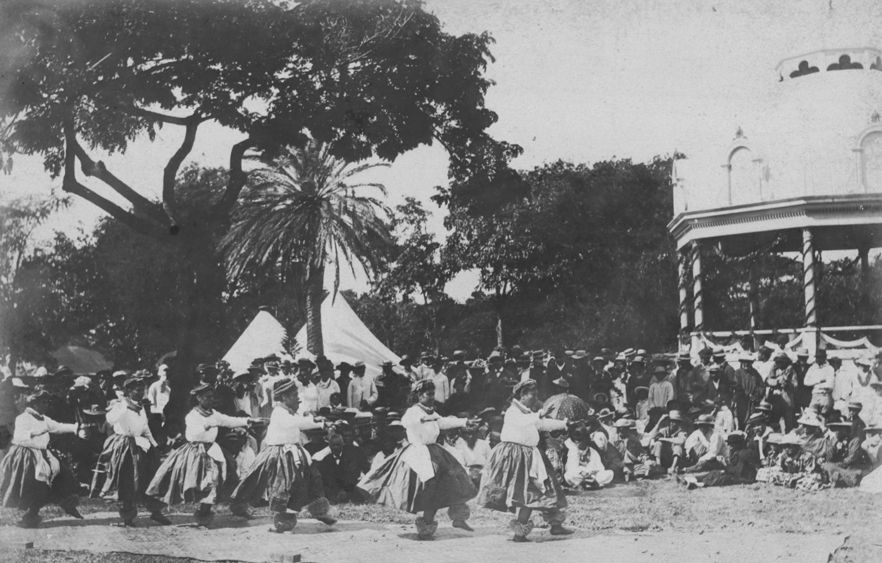

The hula being danced at David’s 49th birthday celebrations; Credit – Wikipedia

During the earlier reigns of Christian converts, dancing the hula was forbidden and punishable by law. Gradually Hawaiian monarchs began to allow the hula but it was David who brought it back in full force. David encouraged Hawaiians with knowledge of the old songs and chants to participate in events and arranged for musicologists to observe and document the old songs and chants. Called the “Merrie Monarch” for his patronage of the arts and the restoration of many Hawaiian cultural traditions during his reign, David is honored by the Merrie Monarch Festival, an annual week-long cultural festival in Hilo, Hawaii, held the week after Easter.

David (in white slacks) aboard the USS Charleston en route to San Francisco; Credit – Wikipedia

On November 25, 1890, David sailed for California aboard the USS Charleston. The purpose of the trip was uncertain but there were reports that the trip was for his ill health. David arrived in San Francisco, California on December 5, 1890. He suffered a minor stroke in Santa Barbara, California, and was rushed back to San Francisco. Two days before his death, he lapsed into a coma. Kalākaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands, born David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Māhinulani Nālaʻiaʻehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua died in San Francisco, California on January 20, 1891, aged 54. He had been under the care of US Navy doctors who listed the cause of his death as nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys.

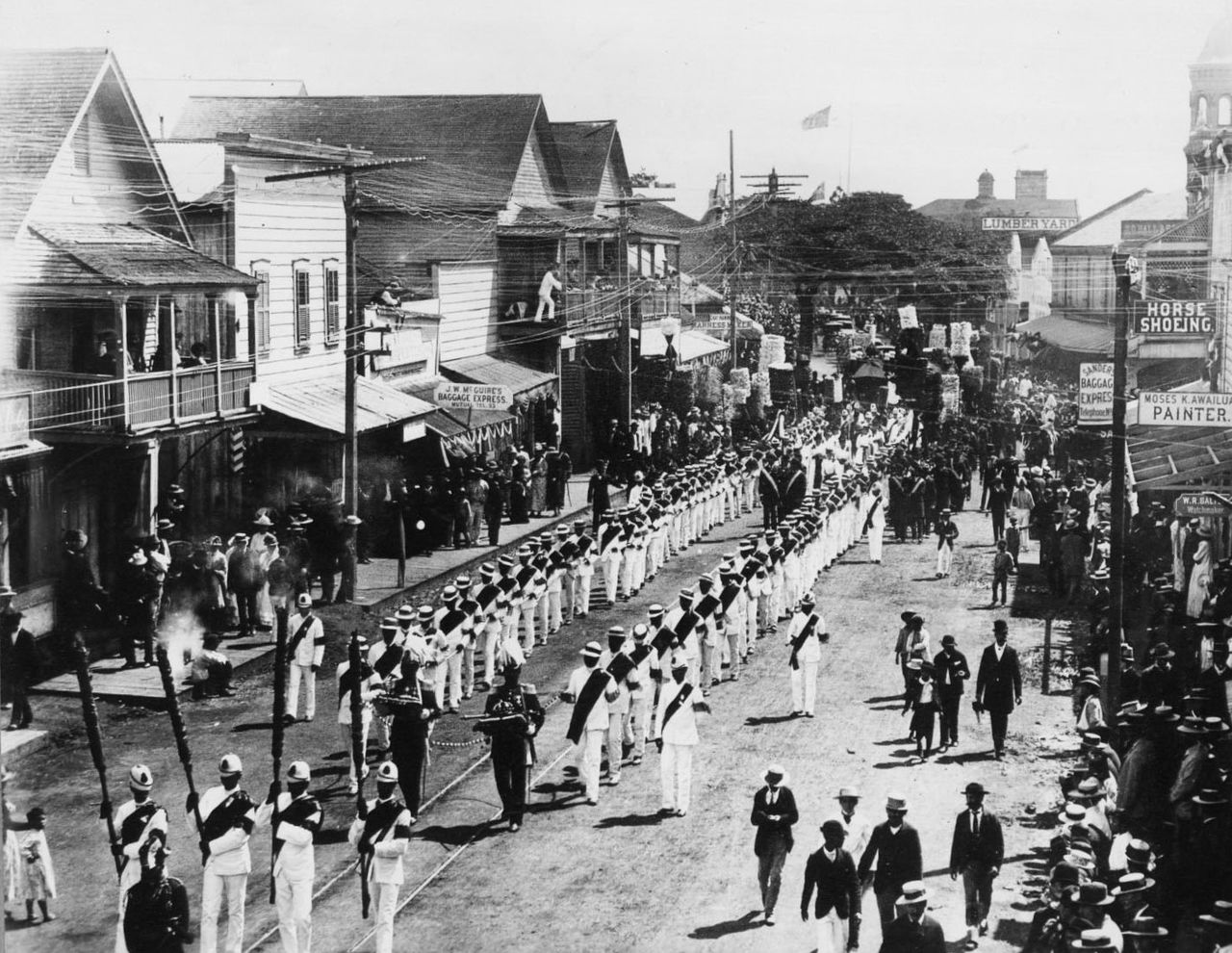

Funeral Procession; Credit – Wikipedia

News of David’s death did not reach Hawaii until January 29, 1891, when the USS Charleston returned to Hawaii with his remains. His sister Liliuokalani ascended to the throne of the Queen of the Hawaiian Islands the same day. After a state funeral, David was buried in the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna ʻAla on February 15, 1891.

Tomb of David and his wife; Credit – Wikipedia

Due to overcrowding, in 1907, the Territory of Hawaii allocated $20,000 for the construction of a separate underground vault for the Kalākaua family. David’s coffin and the coffins of the Kalākaua family were transferred to the new underground Kalākaua Crypt in a ceremony on June 24, 1910, officiated by his sister, the former Queen Liliuokalani.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2024). Kalākaua. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kal%C4%81kaua

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023). Royal Mausoleum (Mauna ʻAla). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Mausoleum_(Mauna_%CA%BBAla)

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023). Hawaiian Kingdom. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawaiian_Kingdom