by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

King Charles I of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Born at Dunfermline Palace in Fife, Scotland on November 19, 1600, Charles was the second son and fourth of the seven children of James VI, King of Scots (later also King James I of England) and Anne of Denmark. Charles’ paternal grandparents were Mary, Queen of Scots and Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, both grandchildren of Margaret Tudor, elder sister of King Henry VIII of England. His maternal grandparents were King Frederik II of Denmark and Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow.

At his christening on December 23, 1600, Charles was created Duke of Albany, the traditional title of the second son of the King of Scots, along with the subsidiary titles of Marquess of Ormond, Earl of Ross and Lord Ardmannoch. At the time of Charles’ birth, his six-year-old elder brother Henry Frederick (named after his grandfathers) was the heir apparent to the throne of Scotland and used the traditional titles of the heir to the Scots’ throne: Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick, and Lord of the Isles.

Charles had six siblings, but only two survived childhood:

- Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales (1594 – 1612), unmarried, died of typhoid fever, aged 18

- Elizabeth (1596 – 1662), married Frederick V, Elector Palatine, had issue including Sophia of Hanover who became heiress presumptive to the British throne under the Act of Settlement 1701; Sophia’s son was King George I of Great Britain

- Margaret (1598 – 1600), died aged fifteen months

- Robert, Duke of Kintyre (born and died 1602), died aged four months

- Mary (1605 – 1607), died aged two.

- Sophia (born and died 1606), lived only one day

On March 24, 1603, Queen Elizabeth I of England died and Charles’ father became King James I of England. Since none of the children of King Henry VIII of England had children, James was the senior heir of King Henry VII of England through his eldest daughter Margaret Tudor. (King Henry VII → Margaret Tudor married King James IV of Scotland → King James V of Scotland → Mary, Queen of Scots → King James VI of Scotland). Charles was frail and late in development, possibly from rickets, and could not yet walk or talk, so he was left behind in Scotland when his parents and his elder brother Henry and elder sister Elizabeth left for England. By July 1604, Charles was considered strong enough to travel to England.

Charles, circa 1610; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1605, Sir Robert Carey was appointed Charles’ governor and his wife Elizabeth patiently taught Charles how to walk and talk. Charles was created Duke of York, the traditional title of the English monarch’s second son in 1605. In the same year, Thomas Murray, a Scottish courtier and later the Provost of Eton College, was appointed Charles’ tutor and taught him classics, languages, mathematics, and religion. Charles overcame his early physical problems, although he grew no taller than five feet four inches, and learned to ride, shoot, and fence. However, he was no physical match for his stronger and taller elder brother Henry, Prince of Wales, whom he adored. When 18-year-old Henry died in 1612 from typhoid, it was a loss that Charles felt greatly. His only surviving sibling Elizabeth left home for her marriage in 1613, and Charles was then virtually an only child. Charles automatically became Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay upon his brother’s death and was created Prince of Wales in 1616.

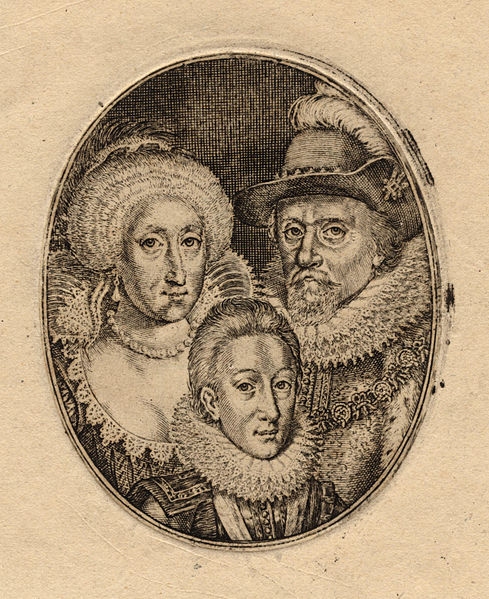

Charles with his parents, after 1612; Credit – Wikipedia

King James I, seeking a Spanish alliance, had visions of Charles marrying Infanta Maria Anna of Spain, the youngest daughter of King Philip III of Spain and Margaret of Austria. In 1623, Charles went to Madrid with his father’s favorite George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham for marriage negotiations regarding the Infanta. The negotiations had long been at a standstill, and although religion was a stumbling block, it is believed that Buckingham’s offensive behavior was a key to the total collapse of the negotiations. The Spanish ambassador asked Parliament to have Buckingham executed for his behavior in Madrid, but Buckingham gained popularity by calling for war with Spain on his return.

Charles as Prince of Wales in 1623; Credit – Wikipedia

While Charles was traveling to Spain in 1623, he first saw King Louis XIII of France‘s sister and his future wife in Paris, Henrietta Maria, as she rehearsed a court entertainment with other members of the French royal family. On March 27, 1625, King James I died and Charles succeeded him. Since the Spanish negotiations failed, King Charles I now looked toward a French alliance and a marriage with Henrietta Maria was successfully negotiated. Henrietta Maria was the youngest daughter of King Henri IV of France and his second wife, Marie de’ Medici. Henri IV was assassinated in 1610 when Henrietta Maria was still a baby and her brother King Louis XIII had succeeded their father. Charles and Henrietta Maria were married by proxy on May 1, 1625, on the steps of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. They were then married in person at Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, England on June 13, 1625. Charles’ coronation was held on February 2, 1626, at Westminster Abbey, but the Roman Catholic Henrietta Maria was not crowned because she refused to participate in a Church of England ceremony. She had proposed that a French Catholic bishop crown her, which was unacceptable to Charles and the English court.

Charles and Henrietta Maria had nine children:

- Charles James, Duke of Cornwall and Rothesay, born and died May 13, 1629

- King Charles II (1630 – 1685), married Catherine of Braganza, no issue, but Charles II had at least 14 illegitimate children

- Mary, Princess Royal (1631 – 1660), married Willem II, Prince of Orange, had one child: Willem III, Prince of Orange, later King William III of England

- King James II (1633 – 1701), married (1) Anne Hyde, had issue including Queen Mary II and Queen Anne; (2) Mary of Modena, had issue including James Francis Edward, The Old Pretender

- Princess Elizabeth (1635 – 1650) unmarried, died from pneumonia

- Princess Anne (1637 – 1640) died young from tuberculosis

- Princess Catherine, born and died June 29, 1639

- Henry, Duke of Gloucester (1640 – 1660) unmarried, died from smallpox

- Princess Henrietta (1644 – 1670), married Philip, Duke of Orléans, had issue

Charles & Henrietta Maria’s five eldest children: L to R: Mary, James, Charles, Elizabeth, and Anne; Credit – Wikipedia

Charles had the same issues with Parliament as his father had, clashing with its members over financial, political, and religious issues. In the early years of Charles’ reign, Parliament was summoned and dissolved three times. Finally, in 1629, Charles, who believed in the divine right of kings, decided to govern without Parliament, beginning eleven years of personal rule. During his personal rule, William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury and Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford were Charles’ most influential advisers. Parliament was finally summoned again in 1640 and demanded the execution of Stafford. Charles signed the death warrant, but never forgave himself. After this incident, the reconciliation of the King and Parliament became impossible.

Charles I in Three Positions by Anthony van Dyck, 1635–36; Credit – Wikipedia

On January 4, 1642, a point of no return was reached. On that day, Charles committed the unprecedented act of entering the House of Commons with an armed guard and demanding the arrest of five Members of Parliament. There was a great public outcry, Charles fled London and Civil War appeared inevitable. Since that day no British monarch has entered the House of Commons when it is sitting and a tradition recalling this is enacted at every State Opening of Parliament. When the monarch arrives in the House of Lords to read the speech from the throne, the Lord Great Chamberlain raises the wand of office to signal to the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod (known as Black Rod), whose duty is to summon the House of Commons. On Black Rod’s approach, the doors to the House of Commons are slammed shut in Black Rod’s face, symbolizing the rights of the House of Commons and its independence from the monarch. Black Rod then strikes the closed doors of the House of Commons with the end of the ceremonial staff (the Black Rod) three times and is then admitted. This is a show of the refusal by the House of Commons never again to be entered by force by the monarch or one of the monarch’s representatives when the House of Commons is sitting.

Speaker Lenthall asserting the Privileges of the Commons (Speaker of the House William Lenthall kneels to Charles during the attempted arrest of the Five Members); Credit – Wikipedia

On August 22, 1642, at Nottingham, Charles raised the Royal Standard and called for his loyal subjects to support him, beginning the Civil War between the Royalists or Cavaliers (Charles’ supporters) and the Roundheads (Parliament’s supporters). The Battle of Edgehill, the first real battle, was fought on October 26, 1642, and proved indecisive. The Cavaliers were defeated at the Battle of Marston Moor on July 2, 1644, and at the Battle of Naseby on June 14, 1645. The balance was now permanently tipped to the parliamentary side. In April 1646, Charles left Oxford, which had served as his capital city during the conflict, and surrendered to the Scottish Army expecting to be safe and well-treated. However, the Scots delivered Charles to Parliament in 1647.

Charles was imprisoned at Holdenby House in Northamptonshire until the New Model Army officer George Joyce took him by force to Newmarket. The New Model Army, created in 1645 to professionalize the Parliamentary army, felt neglected and ignored by Parliament, and Charles thought he could take advantage of these tensions. He was transferred to Oatlands and then Hampton Court Palace where negotiations continued without results. At this point, Charles considered that it would be in his best interest to escape and flee to France, southern England, or the Scottish border or to put himself under the protection of Colonel Robert Hammond, Parliamentary Governor of the Isle of Wight, whom he thought was sympathetic to him. He chose the second option and on November 11, 1647, Charles fled Hampton Court Palace and made arrangements to meet Hammond. However, this proved to be a mistake as Hammond held Charles in Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight and informed Parliament that Charles was in his custody. Charles was confined at Carisbrooke Castle for a year. During this period, Charles continued negotiations with foreign armies and wrote letters showing his lack of respect for Parliament and his determination to abolish anti-Catholic laws. These revelations made any further defense of Charles impossible. He was moved to Hurst Castle in Hampshire at the end of 1648 and then moved to Windsor Castle.

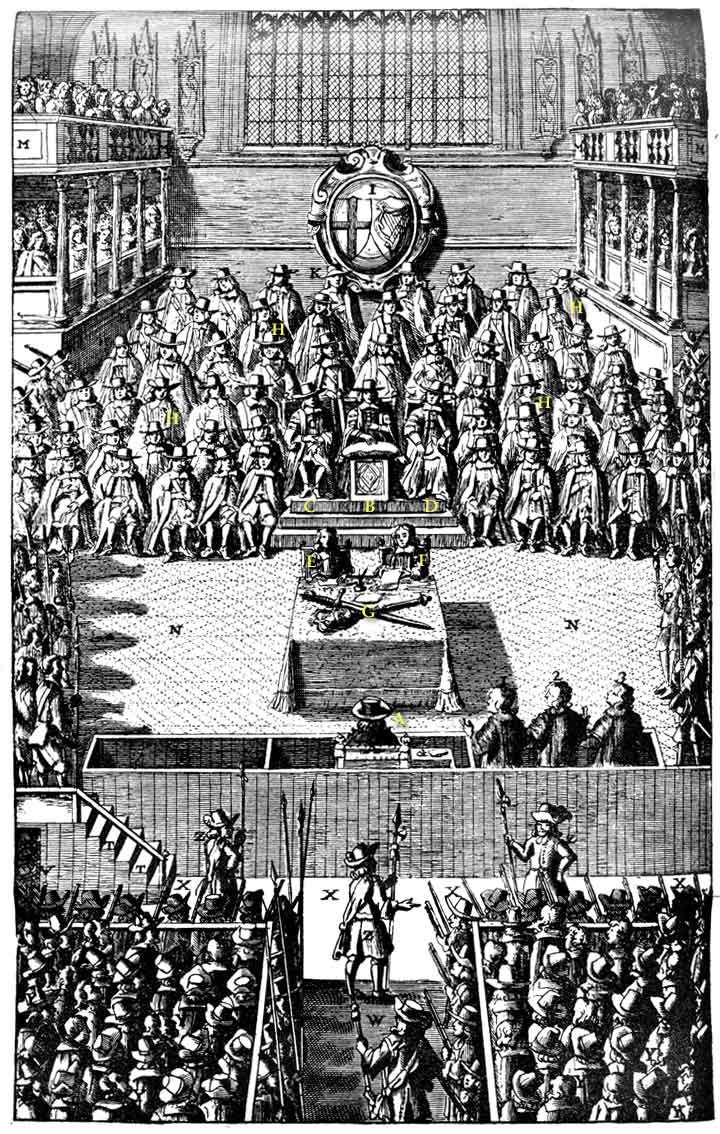

Engraving from “Nalson’s Record of the Trial of Charles I” in the British Museum. Charles (in the dock with his back to the viewer) facing the High Court of Justice; Credit – Wikipedia

On January 20, 1649, Charles was tried for treason and other high crimes in Westminster Hall in London before a tribunal of 135 judges. Charles refused to enter a plea because he believed no court could try a king. Nevertheless, he was found guilty and was sentenced to death. On January 30, 1649, after saying goodbye to his children Elizabeth and Henry, Charles walked from St. James’ Palace to the Palace of Whitehall where a scaffold had been built outside the Banqueting House. It was a cold day, and Charles wore two shirts because he might shiver from the cold and he did not want it thought that he trembled from fear. From the first floor of the Banqueting House, Charles stepped onto the scaffold from a window, and several minutes later was beheaded.

Contemporary German print of Charles I’s beheading; Credit – Wikipedia

No state funeral or public mourning was allowed and Charles was not permitted to be buried in Westminster Abbey. On February 7, 1649, Charles’ remains were taken to Windsor Castle where he was buried at St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle in the choir aisle in the vault where Henry VIII and his third wife Jane Seymour were buried. England was a republic (Commonwealth of England) for 11 years until the monarchy was restored and Charles I’s eldest son Charles II became king in 1660.

Slab in the aisle indicates where Charles I was buried; Credit – www.findagrave.com

Coffins of King Henry VIII (center, damaged), Queen Jane (right), King Charles I with a child of Queen Anne (left), vault under the choir, St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, marked by a stone slab in the floor; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

House of Stuart Resources at Unofficial Royalty