compiled by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

King Charles III of the United Kingdom Credit – Wikipedia

King Charles III is the first British monarch to be descended from two children of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. All monarchs after Queen Victoria have been descendants of her son and heir King Edward VII of the United Kingdom. Through his father, Charles is also a descendant of Princess Alice of the United Kingdom, the second daughter and third child of Queen Victoria. Prince Philip’s royal pedigree also brings a good deal more royal heritage into the British royal family because both of Prince Philip’s parents were royal while only one parent of Queen Elizabeth II was royal.

Parents, Grandparents, Great-Grandparents, Great-Great-Grandparents, and Great-Great-Great-Grandparents of King Charles III of the United Kingdom (born November 14, 1948)

- Unofficial Royalty: King Charles III of the United Kingdom

- Unofficial Royalty: House of Windsor Index

The links below are from Unofficial Royalty, Wikipedia, or The Peerage.

Parents

Prince Charles’ parents; Credit – Wikipedia

- Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark (1921 – 2021)

- Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom (1926 – 2022)

Grandparents

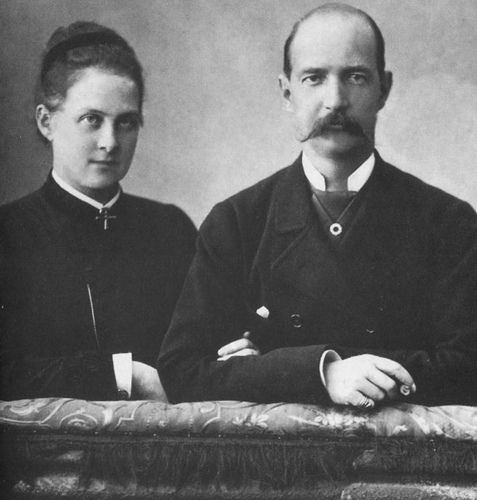

Prince Andrew of Greece and Princess Alice of Battenberg, paternal grandparents; Credit – Wikipedia

- Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark (1882-1944)

- Princess Alice of Battenberg (1885-1969)

- King George VI of the United Kingdom (1895-1952)

- Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (1900-2002)

Great-Grand-Parents

King George I of Greece and Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna of Russia, great-grandparents; Credit – Wikipedia

- King George I of Greece (1845-1913) (born Prince Vilhelm of Denmark)

- Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna of Russia (1851-1926)

- Prince Louis of Battenberg (1854-1921) (later Louis Mountbatten, 1st Marquess of Milford Haven)

- Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine (1863-1950)

- King George V of the United Kingdom (1865-1936)

- Princess Victoria Mary of Teck (1867-1953)

- Claude Bowes-Lyon, 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne (1855-1944)

- Cecilia Nina Cavendish-Bentinck (1862-1938)

Great-Great-Grandparents

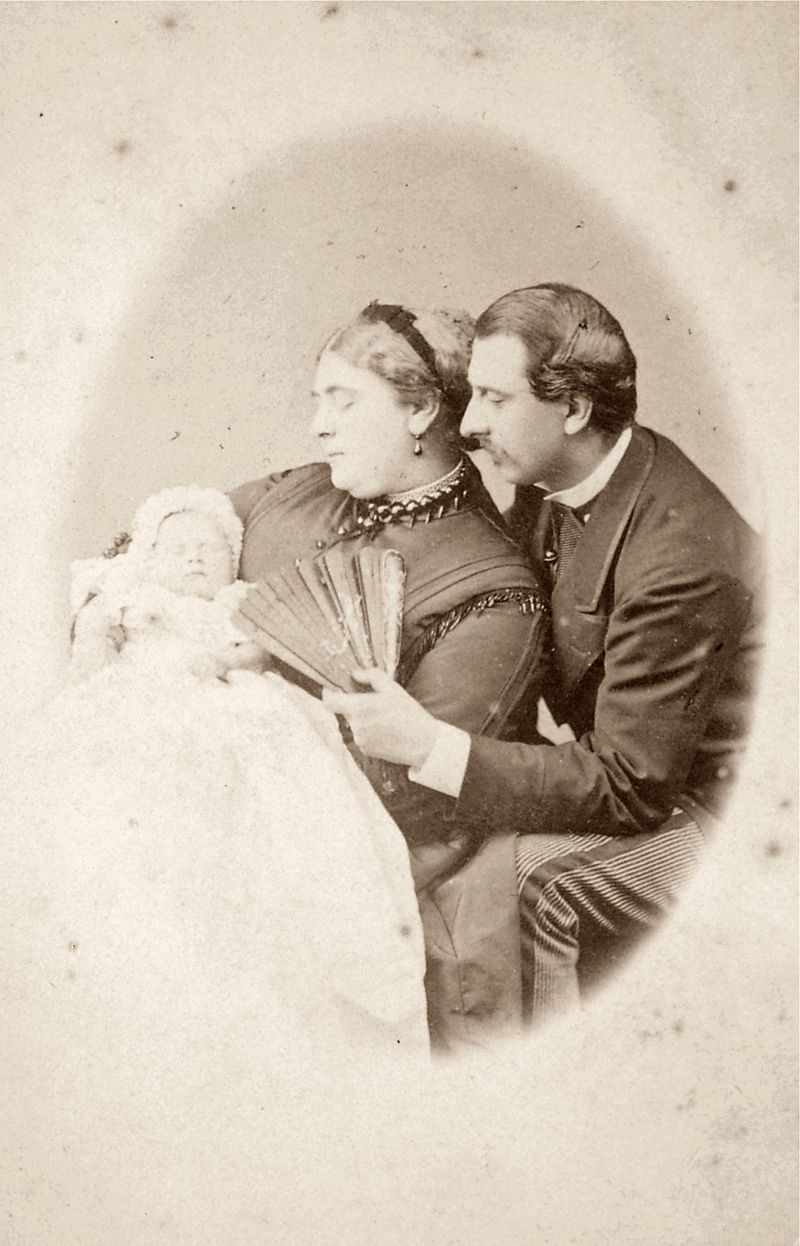

Great-great-grandparents Prince Francis of Teck and Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge with the daughter Princess Victoria Mary of Teck, Prince Charles’ great-grandmother; Credit – Wikipedia

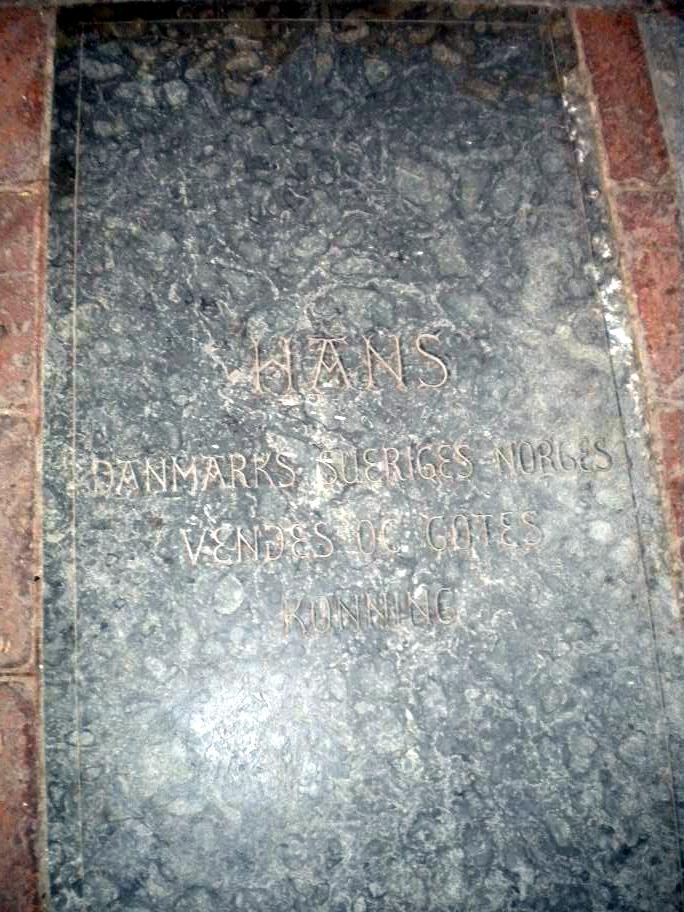

- King Christian IX, King of Denmark (1818-1906) (born Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg)

- Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel (1817-1898)

- Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich of Russia (1827-1892)

- Princess Alexandra of Saxe-Altenburg (1830-1911)

- Prince Alexander of Hesse and by Rhine (1823-1888)

- Countess Julia Hauke (1825-1895)

- Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine (1837-1892)

- Princess Alice of the United Kingdom (1843-1878)

- King Edward VII of the United Kingdom (1841-1910)

- Princess Alexandra of Denmark (1844-1925)

- Francis, Duke of Teck (1837-1900)

- Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge (1833-1897)

- Claude Bowes-Lyon, 13th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne (1824-1904)

- Frances Dora Smith (1832-1922)

- Reverend Charles Cavendish-Bentinck (1817-1865)

- Caroline Louisa Burnaby (1832-1918)

Great-Great-Great-Grandparents

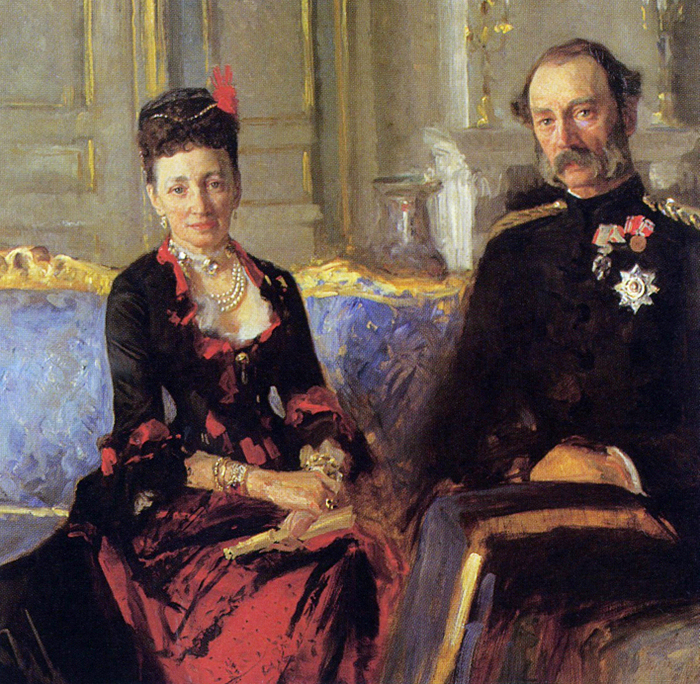

King Christian IX of Denmark and Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel; great-great-great-grandparents; Credit – Wikipedia

- Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg (1785-1831)

- Princess Louise Caroline of Hesse-Kassel (1789-1867)

- Prince Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel (1787-1867)

- Princess Louise Charlotte of Denmark (1789–1864)

- Nicholas I, Emperor of All Russia (1796-1855)

- Princess Charlotte of Prussia (1798-1860)

- Joseph, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg (1789-1868)

- Duchess Amelia of Württemberg (1799-1848)

- Ludwig II, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine (1777-1848)

- Princess Wilhelmine of Baden (1788-1836)

- Count John Maurice Hauke (1775-1830)

- Sophie Lafontaine (circa 1790-1831)

- Prince Karl of Hesse and by Rhine (1809-1877)

- Princess Elisabeth of Prussia (1815-1885)

- Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819-1861)

- Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom (1819-1901)

- Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819-1861)

- Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom (1819-1901)

- King Christian IX of Denmark (1818-1906) (born Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg)

- Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel (1817-1898)

- Duke Alexander of Württemberg (1804-1885)

- Countess Claudine Rhédey von Kis-Rhéde (1812-1841)

- Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge

- Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel

- Thomas Lyon-Bowes, Lord Glamis (1801-1834)

- Charlotte Grimstead (1797-1881)

- Oswald Smith (1794–1863)

- Henrietta Mildred Hodgson (1805-1891)

- Lord Charles Cavendish-Bentinck (1780-1826)

- Anne Wellesley (1788-1875)

- Edwyn Burnaby (1798-1867)

- Anne Caroline Salisbury (1805-1881)

Sources:

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.