by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Sophie of Pomerania, Queen of Denmark and Norway; Credit – Wikipedia

Sophie of Pomerania, Queen of Denmark and Norway was born circa 1498 in Stettin, Duchy of Pomerania, now Szczecin, Poland. Stettin was also the birthplace of Catherine II (the Great) of Russia who was born there as Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst while her father, a general in the Prussian Army, was serving as Governor of Stettin. Sophie of Pomerania was the fourth of the eight children and the second of the three daughters of Bogislaw X, Duke of Pomerania and his second wife Princess Anna Jagiellon of Poland, daughter of King Casimir IV of Poland and Archduchess Elisabeth of Austria. The first marriage of Sophie’s father to Margarete of Brandenburg was childless.

Sophie had seven siblings:

- Anna of Pomerania (1492 – 1550), married Georg I, Duke of Liegnitz and Brieg, no children

- Georg I, Duke of Pomerania (1493 – 1531), married (1) Amalie of the Palatinate, had two sons and one daughter (2) Margarete of Brandenburg, had one daughter

- Casimir of Pomerania (1494 – 1518), unmarried

- Elisabeth of Pomerania (1499 – 1518), unmarried, Abbess of Krummin Nunnery

- Barnim of Pomerania (1500 – 1501), died in infancy

- Barnim IX, Duke of Pomerania (1501 – 1573), married Anna of Brunswick-Lüneburg, had seven children

- Otto of Pomerania (1502 – 1518), died in childhood

Frederik I, King of Denmark and Norway; Credit – Wikipedia

On October 9, 1518, in Kiel, Duchy of Holstein, now in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, twenty-year-old Sophie became the second wife of forty-seven-year-old Frederik of Denmark, the youngest of the four sons but the second surviving son of Christian I, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden and Dorothea of Brandenburg. Frederik was co-Duke of Schleswig and Holstein with his elder brother King Hans of Denmark and Norway. Frederik’s first wife Anna of Brandenburg had died from tuberculosis in 1514 at the age of 26.

Sophie became the stepmother of Frederik and Anna’s two children:

- Christian III, King of Denmark and Norway (1503 – 1559), married Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg, had five children

- Dorothea of Denmark, Duchess of Prussia (1504 – 1547), married Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Duke of Prussia, had six children

Sophie and Frederik had six children:

- Johann II, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Haderslev (1521 – 1580), unmarried

- Elisabeth of Denmark (1524 – 1586), married (1) Magnus III, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, no children (2) Ulrich III, Duke of Mecklenburg-Güstrow, had one daughter

- Adolf of Denmark, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp (1526 – 1586), married Christine of Hesse, had ten children

- Anna of Denmark (1527 – 1535), died in childhood

- Dorothea of Denmark (1528 – 1575), married Christof, Duke of Mecklenburg-Gadebusch, no children

- Frederik of Denmark, Prince-Bishop of Hildesheim and Bishop of Schleswig (1532 – 1556), unmarried

Frederik’s nephew Christian II, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden had reigned since the death of his father King Hans in 1513. However, Christian II was deposed in Sweden in 1521 and replaced by Gustav Vasa, the first monarch of the Swedish House of Vasa. By 1523, the Danes also had enough of Christian II and a rebellion started. Christian was forced to abdicate by the Danish nobles and his paternal uncle Frederik, Duke of Schleswig and Holstein was offered the crown on January 20, 1523. Frederik’s army gained control over most of Denmark during the spring, and in April 1523, Christian II and his family left Denmark to live in exile. In 1531, Christian unsuccessfully attempted to reclaim Norway and was imprisoned by his uncle Frederik in castles, albeit in comfortable circumstances, for the last twenty-seven years of his life.

Frederik and Sophie as King and Queen of Denmark; Credit – Wikipedia

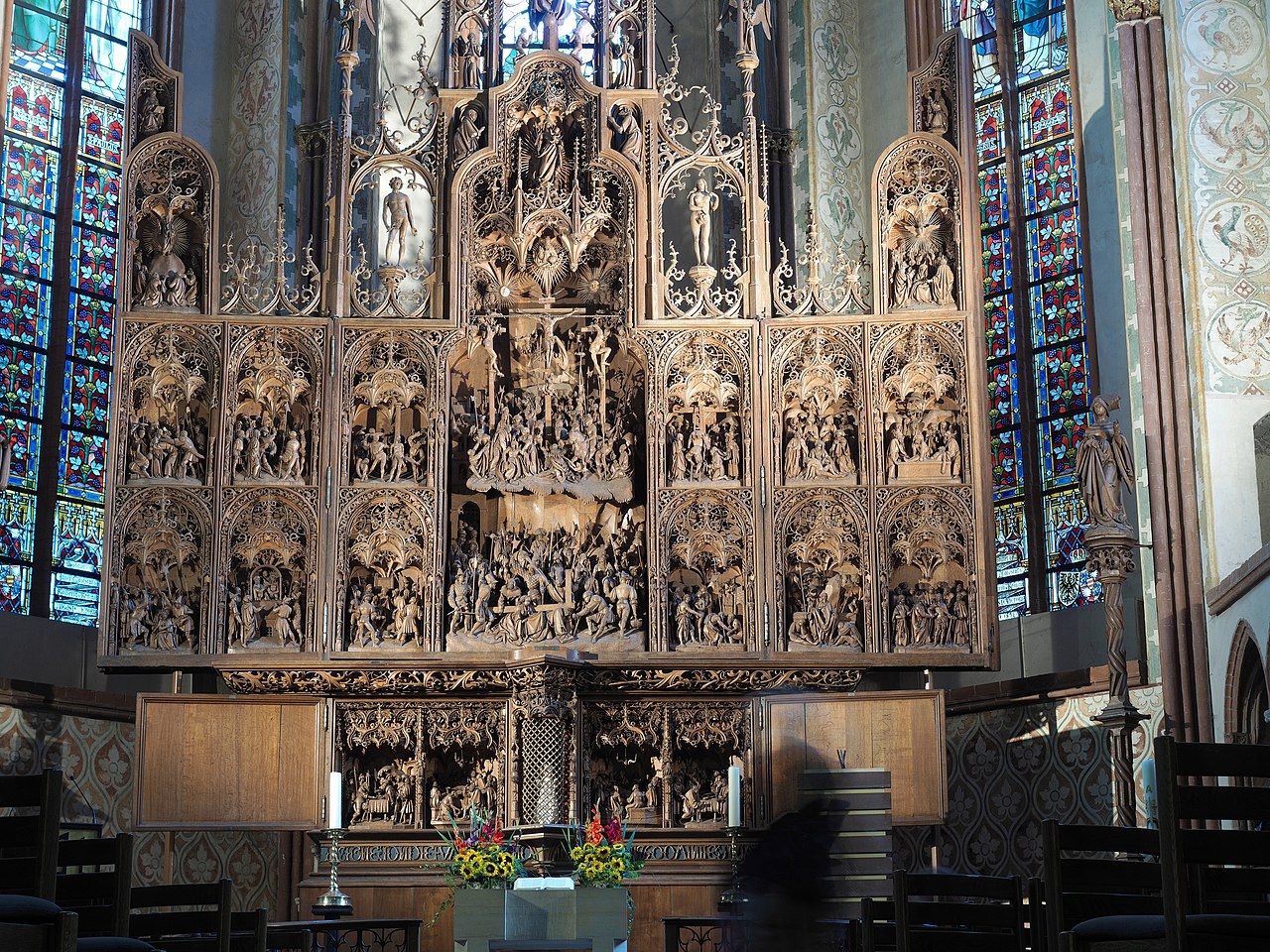

Frederik and Sophie were crowned King and Queen of Denmark on August 13, 1525, at the Cathedral of Our Lady in Copenhagen. Although Frederik was also King of Norway, he and Sophie never visited the country and were never crowned King and Queen of Norway. Frederik occasionally visited Denmark but his main residence was Gottorp Castle in the Duchy of Schleswig. After her coronation, Sophie was granted the Danish islands Lolland and Falster, Kiel Castle and Plön Castle, and several villages in the Duchy of Holstein to provide a means for her income.

After a reign of ten years, Frederik I, King of Denmark and Norway died on April 10, 1533, aged 61, at Gottrop Castle in Gottorp, Duchy of Schleswig, now in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. Frederik was buried in Schleswig Cathedral in Schleswig, Duchy of Schleswig, now in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein.

Sophie’s stepson King Christian III; Credit – Wikipedia

After her husband’s death, when the Danish Council of State was discussing whether the Danish throne should go to her Lutheran stepson the future Christian III, or her Catholic twelve-year-old eldest son Johann, Sophie remained with her children at Gottorp Castle. In 1534, Christian was proclaimed King of Denmark at an assembly of Lutheran nobles in Jutland. However, the Danish Council of State, consisting of mostly Catholic bishops and nobles, refused to accept Christian III as king. Sophie’s son Johann was deemed too young, and the council was more amenable to restoring the deposed King Christian II to the throne because he had supported both the Catholics and Protestant Reformers at various times.

Christopher, Count of Oldenburg, the grandson of a brother of King Christian I of Denmark and the second cousin of both Christian II and Christian III, led the military alliance to restore King Christian II to the throne. A two-year civil war resulted, known as the Count’s Feud, from 1534 – 1536, between Protestant and Catholic forces, that led to King Frederik I’s son from his first marriage ascending the Danish throne as King Christian III.

Sophie had a long dispute with her stepson King Christian III and then his son and successor King Frederik II about her property. First, Christian III claimed Gottorp Castle for himself and forced Sophia to retire to Kiel Castle. Sophie considered the lands her husband had bestowed upon her as her private property. She also had conflicts with Christian III and his son and successor Frederik II over revenue management and the appointment of civil servants.

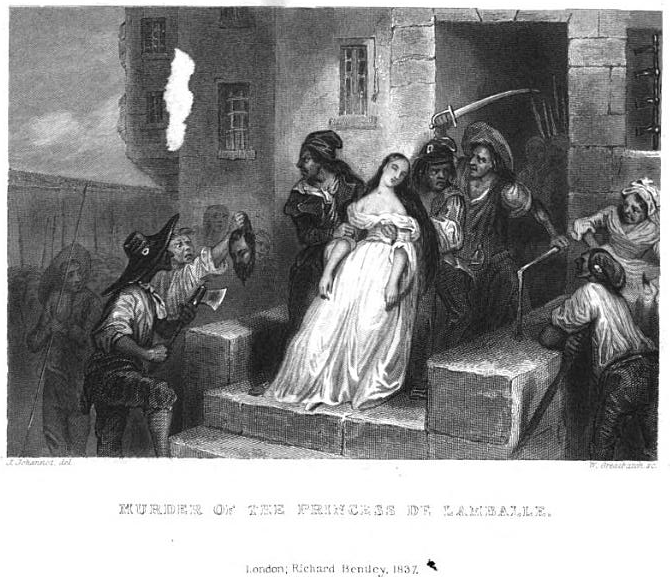

Schleswig Cathedral; Credit – Von Georg Denda, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39310151

Sophie survived her husband King Frederik I by thirty-five years, dying at Kiel Castle on May 13, 1568, at about the age of 70. She was buried with Frederik at Schleswig Cathedral.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Kingdom of Denmark Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Kingdom of Denmark Index

- Danish Orders and Honours

- Danish Royal Burial Sites: House of Oldenburg, 1448 – 1863

- Danish Royal Burial Sites: House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, 1863 – present

- Danish Royal Christenings

- Danish Royal Dates

- Danish Royal Residences

- Danish Royal Weddings

- Line of Succession to the Danish Throne

- Profiles of the Danish Royal Family

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Count’s Feud. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Count%27s_Feud> [Accessed 28 December 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Sophie Of Pomerania. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophie_of_Pomerania> [Accessed 28 December 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan. 2021. Frederik I, King of Denmark and Norway. [online] Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/frederik-i-king-of-denmark-and-norway/> [Accessed 27 December 2020].

- Nl.wikipedia.org. 2020. Sophia Van Pommeren (1498-1568). [online] Available at: <https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophia_van_Pommeren_(1498-1568)> [Accessed 28 December 2020].

- Pl.wikipedia.org. 2020. Zofia Pomorska (1501–1568). [online] Available at: <https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zofia_pomorska_(1501%E2%80%931568)> [Accessed 28 December 2020].