by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Frederik I, King of Denmark and Norway; Credit – Wikipedia

Born on October 7, 1471, in Hadersleben, Duchy of Schleswig, now Haderslev, Denmark, Frederik I, King of Denmark and Norway was the youngest of the four sons and the youngest of the five children of Christian I, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden and Dorothea of Brandenburg.

Frederik had four elder siblings but his eldest two siblings died young. He was fifteen years younger than his closest sibling Margaret.

- Oluf of Denmark (1450 – 1451), died in infancy

- Knud of Denmark (1451 – 1455), died in childhood

- Hans, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (1455 – 1513), married Christina of Saxony, had six children, including King Christian II

- Margaret of Denmark, Queen of Scots (1456 – 1486), married James III, King of Scots, had three children including James IV, King of Scots; Margaret and James III are ancestors of the British royal family and several other European royal families

Frederik’s father Christian I, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, and also Duke of Schleswig and Holstein, died in 1481 when Frederik was ten-years-old. During King Christian I’s life, his wife Queen Dorothea had asked her husband to leave the Duchy of Schleswig and the Duchy of Holstein to Frederik. However, upon the death of King Christian I, his son and successor King Hans I instead insisted on German inheritance law, which meant both brothers would be co-rulers of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein.

Until Frederik reached his majority in 1490, his mother Queen Dorothea was co-ruler as regent of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein with her son King Hans. Frederik grew up at Gottorp Castle in the Duchy of Schleswig, now in Schleswig in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. He was educated at Bordesholm Monastery (link in German) in the Duchy of Schleswig. Although the duchies could not be divided, Queen Dorothea arranged for the income from both duchies to be divided equally between the two brothers, who both held the title Duke of Schleswig and Holstein.

The double wedding in Stendal in 1502; Credit – Wikipedia

On April 10, 1502, in Stendal, Electorate of Brandenburg, now in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt, thirty-one-year-old Frederik married fifteen-year-old Anna of Brandenburg, daughter of Johann II, Elector of Brandenburg and Margaret of Thuringia. Their marriage was a double ceremony as Anna’s brother Joachim I Nestor, Elector of Brandenburg and Frederik’s niece Elisabeth of Denmark, daughter of King Hans of Denmark, were also married.

Frederik and his first wife Anna of Brandenburg; Credit – Wikipedia

Frederik and Anna had two children:

- Christian III, King of Denmark and Norway (1503 – 1559), married Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg, had five children

- Dorothea of Denmark, Duchess of Prussia (1504 – 1547), married Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Duke of Prussia, had six children

Having two children during her teenage years weakened Anna’s health. She contracted tuberculosis and died on May 3, 1514, aged 26, while six months pregnant. Anna was buried in the Bordesholm Monastery Church in the Duchy of Schleswig. After Anna’s death, Frederik I ordered a magnificent tomb with bronze effigies of Anna and himself which still stands in Bordesholm Monastery Church. Frederik planned to be buried there but he was buried elsewhere.

Sophie of Pomerania, Frederik’s second wife; Credit – Wikipedia

Four years after Anna’s death, forty-seven-year-old Frederik married twenty-year-old Sophie of Pomerania on October 9, 1518, in Kiel, Duchy of Holstein, now in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. Sophia was the daughter of Bogislaw X, Duke of Pomerania and Princess Anna Jagiellon of Poland.

Sophie and Frederik had six children:

- Johann II, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Haderslev (1521 – 1580), unmarried

- Elisabeth of Denmark (1524 – 1586), married (1) Magnus III, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, no children (2) Ulrich III, Duke of Mecklenburg-Güstrow, had one daughter

- Adolf of Denmark, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp (1526 – 1586), married Christine of Hesse, had ten children

- Anna of Denmark (1527 – 1535), died in childhood

- Dorothea of Denmark (1528 – 1575), married Christof, Duke of Mecklenburg-Gadebusch, no children

- Frederik of Denmark, Prince-Bishop of Hildesheim and Bishop of Schleswig (1532 – 1556), unmarried

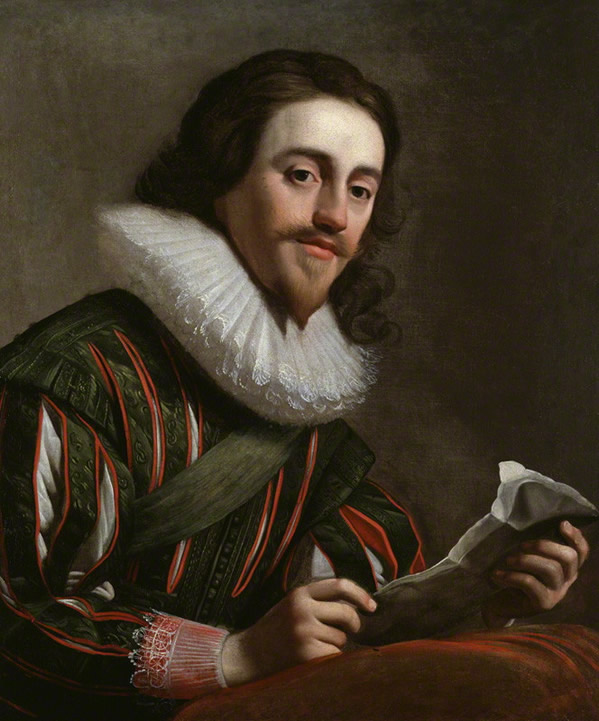

Frederik’s nephew King Christian II; Credit – Wikipedia

Frederik’s nephew Christian II, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden had been deposed in Sweden in 1521 and replaced by Gustav Vasa, the first monarch of the Swedish House of Vasa. By 1523, the Danes also had enough of Christian II and a rebellion started. Christian II was forced to abdicate by the Danish nobles and his paternal uncle Frederik, Duke of Schleswig and Holstein was offered the crown on January 20, 1523. Frederik’s army gained control over most of Denmark during the spring, and in April 1523, Christian II and his family left Denmark to live in exile. In November 1531, Christian II attempted to reclaim Norway but was unsuccessful. He accepted a promise of safe-conduct from his uncle Frederik I but Frederik had enough of his nephew Christian. He did not keep his promise, and instead, Christian was imprisoned in castles, albeit in comfortable circumstances, for the last twenty-seven years of his life.

Although Frederik was King of Norway, he never visited the country and was never crowned as King of Norway. He did visit Denmark but he kept his main residence at Gottorp Castle in the Duchy of Schleswig. It is not certain if Frederik ever learned to speak Danish. Frederik was the last Roman Catholic Danish monarch. All subsequent Danish monarchs have been Lutheran. Although Frederik remained Catholic, he was somewhat tolerant of the new Protestant Lutheran religion. He ordered Lutherans and Roman Catholics share the same churches and encouraged the first publication of the Bible in the Danish language. When Lutheran reformer Hans Tausen was threatened with arrest and trial for heresy, Frederick appointed him his personal chaplain to give him immunity. Frederik’s attitude toward religion postponed the all-out warfare between Protestants and Roman Catholics that occurred during the reign of his son King Christian III, ultimately turning Denmark into a Protestant nation.

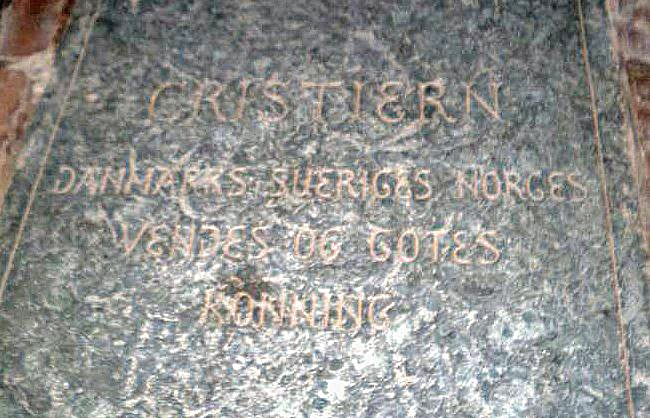

After a reign of ten years, King Frederik I died on April 10, 1533, aged 61, at Gottrop Castle in Gottorp, Duchy of Schleswig, now in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. Instead of being buried with his first wife Anna at the Bordesholm Monastery Church where a tomb was awaiting him, Frederik was buried in Schleswig Cathedral in Schleswig, Duchy of Schleswig, now in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. His second wife Sophie survived him by thirty-five years, dying on May 13, 1568, at about the age of 70. Sophie was buried with Frederik at Schleswig Cathedral.

Tomb of Frederik I; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Kingdom of Denmark Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Kingdom of Denmark Index

- Danish Orders and Honours

- Danish Royal Burial Sites: House of Oldenburg, 1448 – 1863

- Danish Royal Burial Sites: House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, 1863 – present

- Danish Royal Christenings

- Danish Royal Dates

- Danish Royal Residences

- Danish Royal Weddings

- Line of Succession to the Danish Throne

- Profiles of the Danish Royal Family

Works Cited

- Da.wikipedia.org. 2020. Frederik 1. [online] Available at: <https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederik_1.> [Accessed 26 December 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Frederick I Of Denmark. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_I_of_Denmark> [Accessed 26 December 2020].

- De.wikipedia.org. 2020. Friedrich I. (Dänemark Und Norwegen). [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_I._(D%C3%A4nemark_und_Norwegen)> [Accessed 26 December 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan. 2020. Christian I, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. [online] Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/christian-i-king-of-denmark-norway-and-sweden/> [Accessed 26 December 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan. 2020. Christian II, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/christian-ii-king-of-denmark-norway-and-sweden/> [Accessed 26 December 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan. 2020. Hans, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/hans-king-of-denmark-norway-and-sweden/> [Accessed 26 December 2020].