by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

Kingdom of Tonga: Tonga consists of 169 islands, of which 36 are inhabited, in the south Pacific Ocean, about 1,100 miles/1,800 kilometers northeast of New Zealand’s North Island.

Tonga has long been a monarchy and by the 12th century, Tonga and its Paramount Chiefs had a strong reputation throughout the central Pacific Ocean. Tonga became a kingdom in 1845 and has been ruled by the House of Tupou. From 1900 to 1970, Tonga had a protected state status with the United Kingdom which looked after its foreign affairs under a Treaty of Friendship.

The order of succession to the throne of Tonga was established in the 1875 constitution. The crown descends according to male-preference cognatic primogeniture – a female can succeed if she has no living brothers and no deceased brothers who left surviving legitimate descendants.

********************

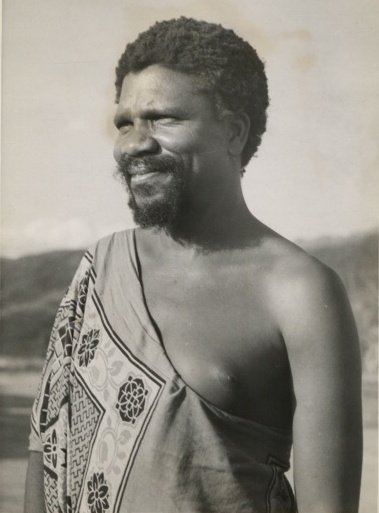

King Tāufaʻāhau Tupou IV of Tonga; Credit – Wikipedia

King Tāufaʻāhau Tupou IV of Tonga was born on July 4, 1918, at the Royal Palace in Nukuʻalofa, Tonga, the eldest of the three sons of Queen Sālote Tupou III of Tonga and her husband Prince Viliami Tungī Mailefihi.

Tonga royal family, circa 1930, Front (L to R): Prince Uiliami Tukuʻaho, Prince Sione Ngū Manumataong; Seated (L to R): Prince Viliami Tungī Mailefihi, Queen Sālote Tupou III; Back (L to R): Prince Siaosi Tāufaʻāhau Tupoulahi (later King Tāufaʻāhau Tupou IV), Princess Fusipala, half-sister of Queen Salote; Credit – By Unknown author – Wood-Ellem, Elizabeth (1999) Queen Sālote of Tonga: The Story of an Era 1900–1965, Auckland, N.Z: Auckland University Press, pp. 144–145 ISBN: 978-0-8248-2529-4. OCLC: 262293605., CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1211166

Tāufaʻāhau Tupou had two younger brothers:

- Prince Uiliami Tuku‘aho (1920 – 1936), died as a teenager

- Prince Sione Ngū Manumataongo (1922 – 1999), married Melenaite Tupoumoheofo Veikune, had four daughters and two sons

Tāufaʻāhau Tupou in 1928; Credit – Wikipedia

Tāufaʻāhau Tupou began his education at a school run by the Free Wesleyan Church in Tonga and continued at Tupou College, a Methodist boys’ secondary boarding school in Toloa, Tonga. While at Tupou College, Tāufaʻāhau Tupou began competing in the pole vault, and by the age of fourteen, he held the Tonga pole vault record, a record that stood for many years.

Tāufaʻāhau Tupou pole vaulting, circa 1935; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1932, at the age of 14, Tāufaʻāhau Tupou was sent to Newington College, an exclusive boys’ secondary school located in Stanmore, near Sydney, Australia. While at Newington College, Tāufaʻāhau Tupou was a member of the athletic (track) team and competed in the pole vault. After finishing his secondary education at Newington College, Tāufaʻāhau Tupou attended the University of Sydney in Australia from 1938-1942, receiving both a bachelor’s degree and a law degree.

Tāufaʻāhau Tupou is seated on the far right with his fellow athletic team members; Credit – Wikipedia

Upon graduating from university, Tāufaʻāhau Tupou returned to Tonga and began a career in government. His mother Queen Sālote appointed him Minister of Education in 1943, Minister of Health in 1944, and in 1949, he was appointed Prime Minister of Tonga, a position he held until he became King of Tonga in 1965. Tāufaʻāhau Tupou was a lay preacher of the Free Wesleyan Church of Tonga until his death.

On June 10, 1946, Tāufaʻāhau Tupou married Halaevalu Mataʻaho ʻAhomeʻe (1926 – 2017) and the couple had four children:

- King George Tupou V (1948 – 2012), unmarried

- Princess Royal Salote Mafileʻo Pilolevu Tuita (born 1951), married Siosaʻia Maʻulupekotofa, Lord Tuita of ʻUtungake, had four daughters

- Prince Fatafehi ʻAlaivahamamaʻo Tukuʻaho (1953 – 2004), married (1) Heimataura Seiloni, a commoner so he was stripped of his royal titles, his wife died in 1985 (2) Alaile’ula Poutasi Jungblut, had four children

- King Tupou VI (born 1959), married Nanasipauʻu Tukuʻaho, daughter of Baron Vaea, a former Prime Minister of Tonga, had one daughter and two sons

Embed from Getty Images

Coronation of Tongan King Taufa’auhau Tupou IV

Upon the death of his mother Queen Sālote Tupou III in 1965, Tāufaʻāhau Tupou became King of Tonga. Taufa’ahau Tupou IV was crowned King of Tonga in a Methodist ceremony on July 4, 1967, his 49th birthday, at the Royal Chapel on the grounds of the Royal Palace in Nukuʻalofa, Tonga. Tongans from the outer islands had been arriving in the capital Nuku’alofa for a month. Dignitaries who attended included the Duke and Duchess of Kent representing Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom and New Zealand’s Prime Minister Keith Holyoake.

In 1970, King Tāufaʻāhau Tupou proclaimed Tonga’s full independence from the United Kingdom, which had held Tonga as a protectorate since 1900. For most of his reign, King Tāufaʻāhau Tupou had the respect and loyalty of his subjects and other leaders in the South Pacific but toward the end of his reign, he faced increasing dissent. In 2005, thousands of people took to the streets to demand democracy and public ownership of key assets. Like his mother Queen Sālote, King Tāufaʻāhau Tupou‘s stature was notable. He was 6 feet 5 inches tall and weighed 440 pounds. In the 1990s, he took part in a national fitness campaign, and by his 80th birthday, in 1998, he had lost 286 pounds.

Embed from Getty Images

King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV, age 84, relaxing in the Royal Palace, 2002

On September 10, 2006, 88-year-old King Tāufaʻāhau Tupou IV of Tonga died at Mercy Hospital in Auckland, New Zealand. His funeral, which blended Christian and ancient Polynesian burial rites, was held on September 19, 2006, in the Tongan capital, Nukuʻalofa. Thousands of Tongans attended the funeral along with many foreign dignitaries, including Japanese Crown Prince Naruhito, New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark, Fijian Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase, Vanuatu President Kalkot Mataskelekele, American Samoan Governor Togiola Tulafono, Niue Premier Vivian Young, and the Duke of Gloucester representing his cousin of Queen Elizabeth of the United Kingdom. King Tāufaʻāhau Tupou IV of Tonga was buried his mother Queen Sālote at Malaʻekula, the royal burial grounds in Nukuʻalofa, the capital of the Kingdom of Tonga.

Tongan Royal Tombs, King Tāufaʻāhau Tupou’s tomb is the first statue on the right; Credit – Around the Globe with the Rosens

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Baker, Simon, 2006. King’s Funeral Mixes Tongan, Western Traditions. [online] The Age. Available at: <https://www.theage.com.au/world/kings-funeral-mixes-tongan-western-traditions-20060920-ge364c.html> [Accessed 8 September 2020].

- BBC News. 2006. Tongan King Tupou IV Dies At 88. [online] Available at: <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/5333318.stm> [Accessed 8 September 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Tāufaʻāhau Tupou IV. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C4%81ufa%CA%BB%C4%81hau_Tupou_IV> [Accessed 8 September 2020].

- NYtimes.com. 2006. King Taufa’Ahau Tupou IV, Ruler Of Tonga, Dies At 88. [online] Available at: <https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/11/world/asia/11tonga.html?ref=oembed> [Accessed 8 September 2020].

- NZ Herald. 2006. King’s Funeral Brings Capital To Halt. [online] Available at: <https://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/news/article.cfm?c_id=2&objectid=10401988> [Accessed 8 September 2020].

- The Guardian. 2006. Obituary: King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV Of Tonga. [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/sep/20/guardianobituaries.rogercowe> [Accessed 8 September 2020].