by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

On the night of March 23, 1801, at the Mikhailovsky Castle in St. Petersburg, Russia, a group of conspirators charged into the bedroom of 46-year-old Paul I, Emperor of All Russia, forced him to abdicate, and then strangled and trampled him to death.

Paul I, Emperor of All Russia

Paul I, Emperor of All Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

Paul I, Emperor of All Russia was born on October 1, 1754, at the Summer Palace of Empress Elizabeth in St. Petersburg, Russia. As the son of Grand Duchess Catherine Alexeievna (born Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst, later Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia), Paul was recognized by Catherine’s husband Grand Duke Peter Feodorovich (born Karl Peter Ulrich of Holstein-Gottorp, later Peter III, Emperor of All Russia) as his son. Peter and Catherine’s marriage was not a happy one. Peter took a mistress and Catherine had many lovers. It is possible that Paul’s father was Sergei Vasilievich Saltykov. If this is true, then all subsequent Romanovs were not genetically Romanovs. Catherine later claimed Peter was not the father of her son and successor and that her marriage was never consummated.

Paul was taken from his mother immediately after birth. He spent the first eight years of his life at the court of his great-aunt, Elizabeth I, Empress of All Russia, the daughter of Peter I (the Great), Emperor of All Russia. Elizabeth was the younger sister of Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna, Peter III’s mother who died shortly after his birth. The unmarried and childless Empress Elizabeth named her nephew Peter as her heir.

When Empress Elizabeth died in 1721, when Paul was eight years old, her nephew succeeded her as Peter III, Emperor of All Russia. However, the reign of Peter III lasted only six months. Paul’s mother engineered a coup that not only deposed her husband but also got him killed by her supporters. In the summer of 1762, Paul’s mother began her 34-year reign as Catherine II, Empress of All Russia, known in history as Catherine the Great. When Catherine was finally able to retrieve her eight-year-old son after the death of Empress Elizabeth, it was too late to repair their relationship. Paul’s early isolation from his mother created a distance between them which would only be reinforced by later events.

Family of Paul I of Russia, by Gerhard von Kügelgen, 1800; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1773, Paul married Wilhelmine Louise of Hesse-Darmstadt who became Grand Duchess Natalia Alexeievna after her marriage. Three years later, Natalia Alexeievna and her first child, a boy, died after six days of agonizing labor. Less than six months after his first wife’s death, Paul married Sophia Dorothea of Württemberg who took the name Maria Feodorovna after her marriage. Paul and Maria Feodorovna had ten children with nine surviving to adulthood including two Emperors of All Russia, a Queen of the Netherlands, a Queen of Württemberg, and a Grand Duchess of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach.

The Road to Assassination

Portrait of Paul I in Coronation Robes by Vladimir Lukich Borovikovsky; Credit – Wikipedia

Upon the death of his mother Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia in 1796, Paul succeeded her as Emperor of All Russia. Ironically, Paul I, Emperor of All Russia suffered a fate similar to Peter III. Paul’s reign lasted five years, ending with his assassination by conspirators. As Emperor, Paul agreed with the practices of autocracy and tried to prevent liberal ideas in the Russian Empire. He did not tolerate freedom of thought or resistance against autocracy. Because he overly taxed the nobility and limited their rights, the Russian nobles, by increasing numbers, were against him. Paul’s reign was becoming increasingly despotic. Eventually, the nobility reached their breaking point. As early as the end of 1797, rumors began swirling of a coup d’état being prepared by the nobility.

A conspiracy was organized, some months before it was executed, by Count Peter Ludwig von der Pahlen, Count Nikita Petrovich Panin, and Admiral José de Ribas, with the alleged support of the British ambassador in Saint Petersburg, Charles Whitworth, 1st Earl Whitworth. According to various estimates, the total number of people involved in the conspiracy ranged from 180 to 300 people. It is probable that Paul’s son and heir Alexander knew of the coup d’état plans and that Paul’s wife Maria Feodorovna knew about the existence of plans.

Afraid of intrigues and assassination plots, Paul disliked the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg where he never felt safe. He ordered his birthplace, the dilapidated Summer Palace of Empress Elizabeth in St. Petersburg to be demolished and replaced with a new fortified residence, the Mikhailovsky Castle. In February 1801, Paul and his family moved into the Mikhailovsky Castle.

The Assassination

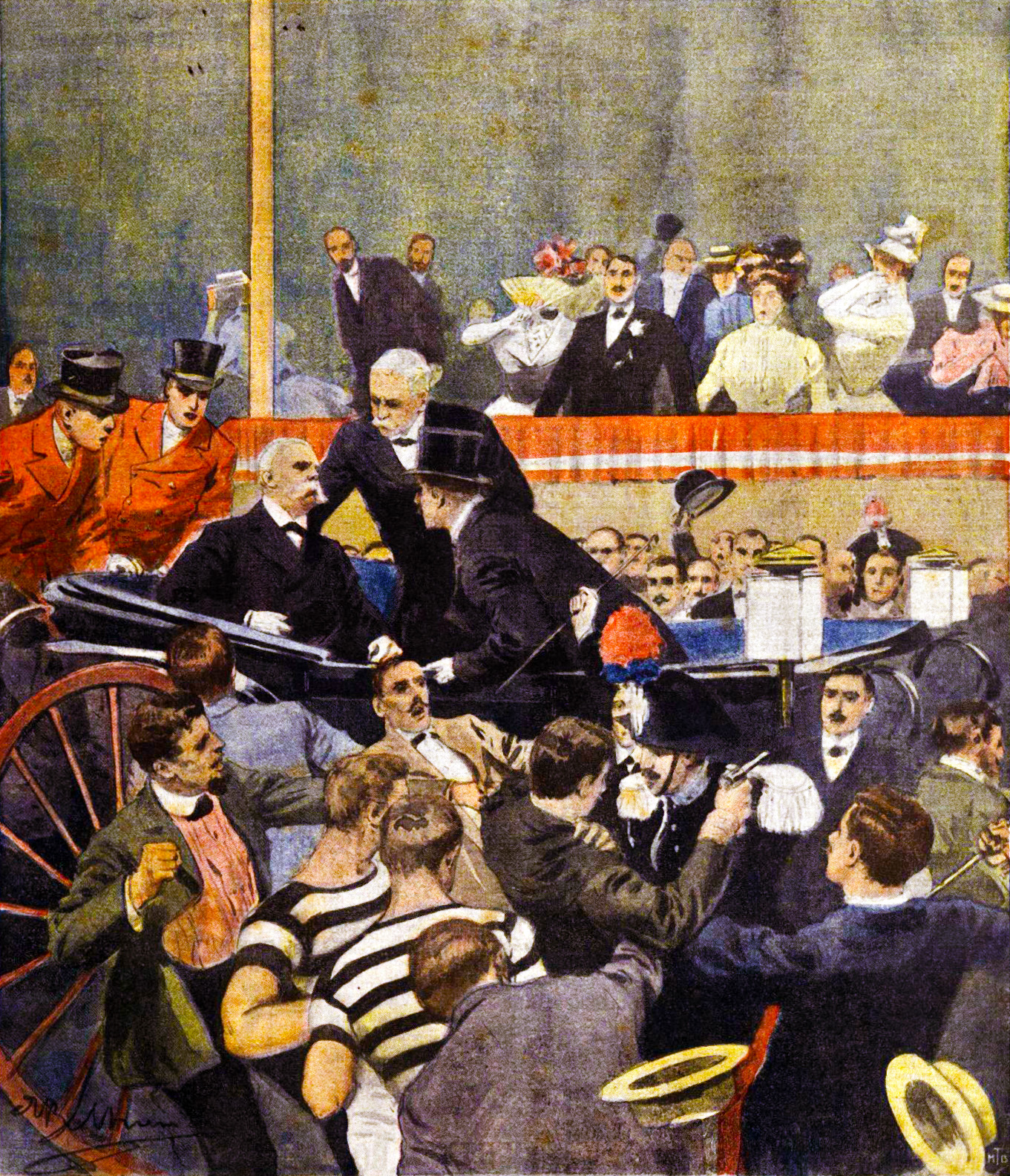

The assassination of Emperor Paul I, French engraving, 1880s; Credit – Wikipedia

At 1:30 AM on March 23, 1801, a group of twelve officers led by Count Nikolai Alexandrovich Zubov and Levin August von Bennigsen, a German general in the service of the Russian Empire, broke into Paul’s bedroom at the Mikhailovsky Castle in St. Petersburg. Also present at the murder were two of the original conspirators Count Nikita Petrovich Panin and Count Peter Ludwig von der Pahlen. The group charged into the bedroom and found Paul hiding behind some drapes in a corner. The conspirators pulled him out and forced him to a table so he could sign an abdication document. When Paul offered some resistance, Count Nikolai Alexandrovich Zubov struck him with a sword, after which the assassins strangled and trampled him to death.

Aftermath

Tomb of Paul I, Emperor of All Russia; Credit – By El Pantera – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36434001

The official cause of Paul’s death was “an apoplexy stroke.” The truth about his assassination was suppressed by censorship. Paul’s body was worked on by a team of doctors all night so it could be displayed as evidence of a natural death. Despite the doctors’ efforts, blue and black spots were visible on Paul’s face. Court painter Jacob Mettenleyter, the curator of the Gatchina Palace art gallery, was summoned with his brushes and paints to make Paul’s face presentable.

One of the doctors described Paul’s body: “There were many traces of violence on the body. A wide strip around the neck, a strong mark on the temple (from a blow … caused by a pistol), a red spot on the side, but not a single wound with a sharp weapon, two red scars on both thighs; significant damage to the knees which prove that he was forced to kneel down to make it easier to strangle. In addition, the whole body was generally covered with small marks; they probably came from blows delivered after death.”

A triangular hat was pulled over Paul’s forehead to hide the injuries to his left eye and his temple. Paul was placed in his coffin in a way that viewers passing by would not be able to see his body clearly. The teenaged Nikolay Ivanovich Gretsch, a future journalist, wrote: “As soon as you enter the door, they pointed to another with an exhortation: if you please go through. I went to Mikhailovsky Castle about ten times and could only see the soles of the emperor’s overboots and a wide hat pulled over his forehead.”

Paul’s eldest son Alexander, who probably knew about the coup but not the murder plot, succeeded as Alexander I, Emperor of All Russia at the age of 23. When Alexander was informed about the murder of his father, he sobbed. Count Nikolai Alexandrovich Zubov told Alexander, “Time to grow up! Go and rule!” Alexander went out on the palace balcony to show himself to the troops and said: “My father died of apoplexy. I will be like my grandmother.” On the first day of his reign, Alexander freed 12,000 prisoners sentenced by his father to prison or exile without a trial. Within a month, Alexander began restoring freedoms that his father revoked. None of the conspirators of the coup d’état resulting in the murder of Emperor Paul were punished. However, over time Alexander I gradually removed the conspirators from their positions, not because he considered them dangerous, but because of the disgust he felt at their very sight.

Paul I, Emperor of All Russia was buried at the Peter and Paul Cathedral in the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg, Russia.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Paul I of Russia. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_I_of_Russia [Accessed 25 Jan. 2018].

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1981). The Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias. New York, NY.: Doubleday

- Flantzer, Susan. (2018). Paul I, Emperor of All Russia. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/emperor-paul-i-of-russia/ [Accessed 5 Jan. 2020].

- Massie, Robert. (2016). Catherine the Great. London: Head of Zeus.

- Ru.wikipedia.org. (2018). Павел I. [online] Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9F%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B5%D0%BB_I [Accessed 25 Jan. 2018]. (Paul I in Russian)

- Ru.wikipedia.org. (2020). Убийство Павла I. [online] Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A3%D0%B1%D0%B8%D0%B9%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%BE_%D0%9F%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%BB%D0%B0_I [Accessed 5 Jan. 2020]. (The assassination of Paul I in Russian)