by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2019

Emperor Hirohito after his enthronement ceremony in 1928; Credit – Wikipedia

Emperor of Japan for 62 years, Hirohito, now known in Japan by his posthumous name Emperor Shōwa, was born during the reign of his grandfather Emperor Meiji, on April 29, 1901, at the Tōgū Palace in Aoyama, Tokyo, Japan. The eldest of the four sons of Crown Prince Yoshihito and Crown Princess Sadako, now known by their posthumous names Emperor Taishō and Empress Teimei, he was given the childhood appellation Michi-no-miya and the personal name Hirohito.

Hirohito in 1902; Credit – Wikipedia

Hirohito had three younger brothers:

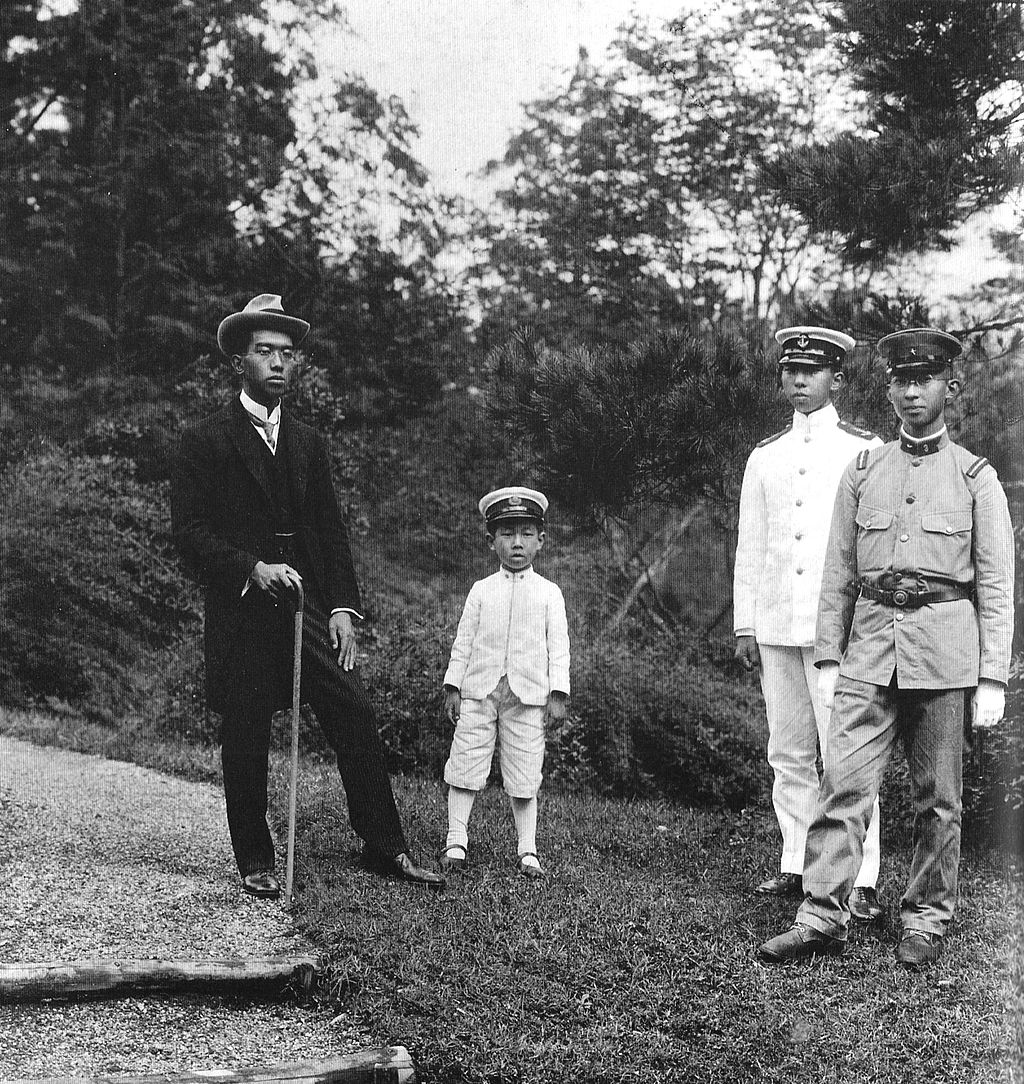

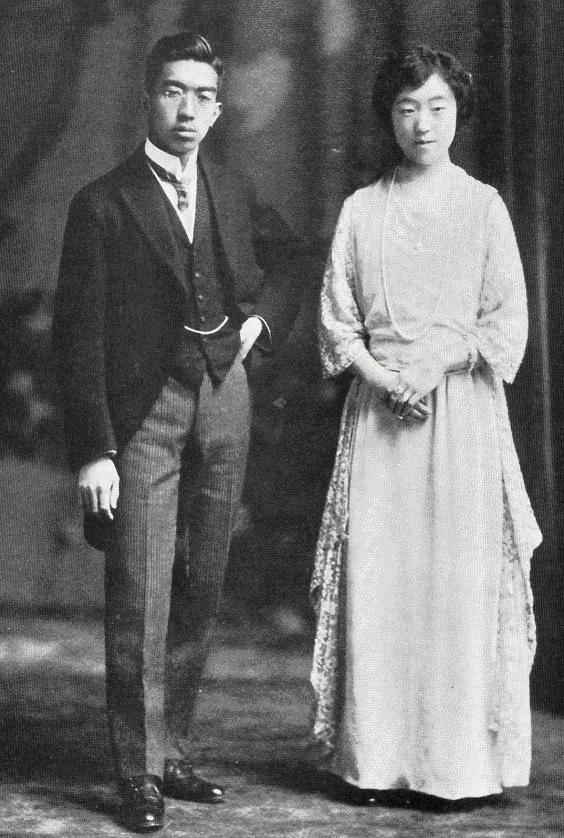

Hirohito and his brothers in 1921: Hirohito, Mikasa, Takamatsu, and Chichibua; Credit – Wikipedia

As was the custom, the infant Hirohito was placed in the care of the family of a noble, Count Kawamura Sumiyoshi, a former vice-admiral. When Kawamura died in 1904, Hirohito and his two-year-old brother Chichibua were returned to court. Starting in 1906, Hirohito attended a kindergarten established at the Aoyama Imperial Palace. From 1908 to 1914, he attended the Gakushūin (Peers School), established to educate the children of the Japanese nobility.

Hirohito’s grandfather Emperor Meiji died on July 30, 1912, and his father Yoshihito became Emperor of Japan, now known by his posthumous name Taishō. Emperor Taishō had cerebral meningitis when he was three weeks old, and this affected his health and his mental capacity, including a speech disorder and difficulty walking, for the rest of his life. Due to his health issues, he had often been unable to continue his studies as a child and had been a poor student in areas requiring higher-level thinking. Because of Emperor Taishō’s weak physical and mental condition, his wife exerted a strong influence during his reign. Emperor Taishō was kept out of public view as much as possible because of mental incapacity.

Crown Prince Hirohito in 1916; Credit – Wikipedia

At the time of his father’s accession to the throne, Hirohito became the heir apparent. He was formally proclaimed Crown Prince on November 2, 1916. From 1914 to 1921, Hirohito attended a special institute to prepare him for his future role as Emperor. Within a few years, it became apparent that Emperor Taishō could not carry out any public functions, participate in daily government matters, or make decisions. This was left to his government ministers and eventually to his son, Crown Prince Hirohito. Finally, Crown Prince Hirohito was named Prince Regent on November 25, 1921.

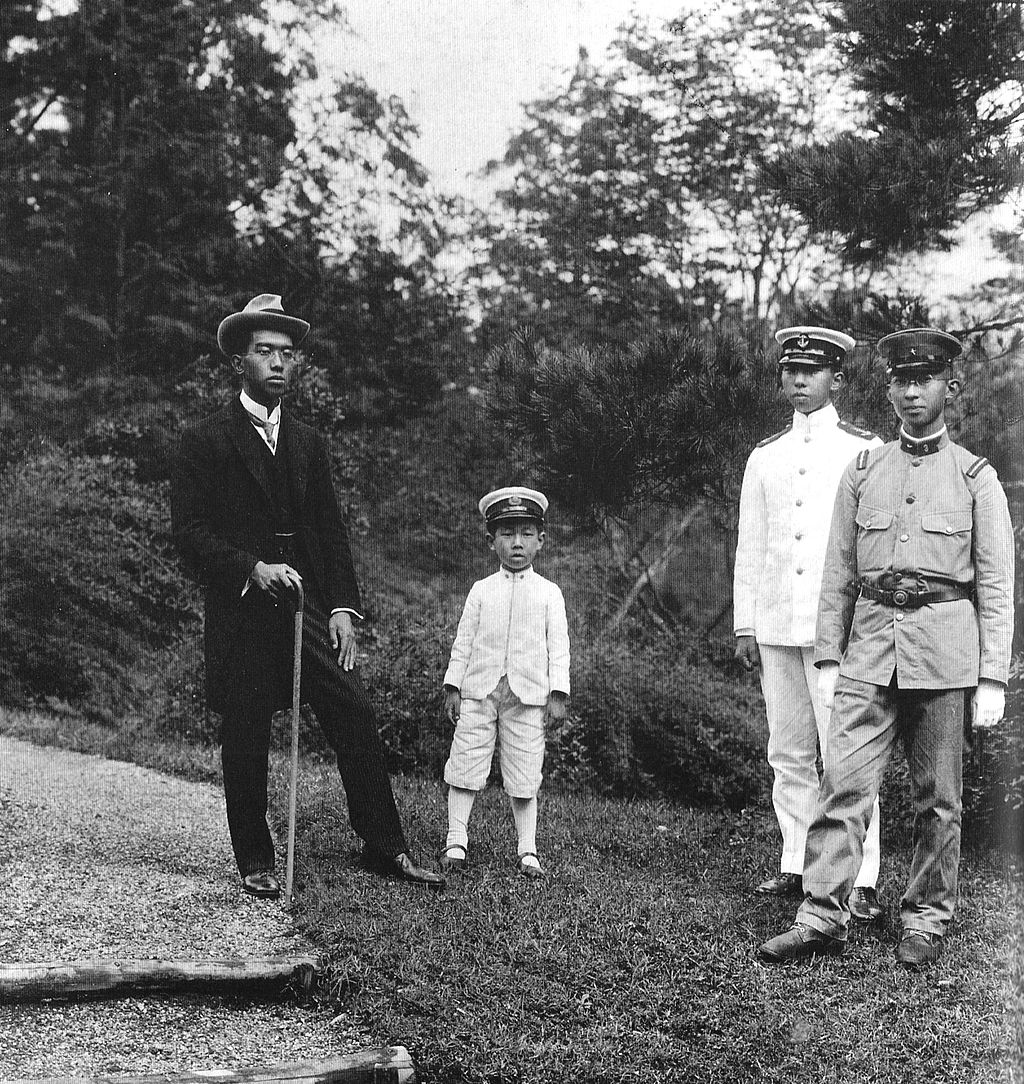

In a step away from tradition, Hirohito was allowed to choose his own bride. In 1917, eligible young women participated in a tea ceremony at the Imperial Palace while Hirohito watched unseen from behind a screen. He selected 14-year-old Princess Nagako Kuni, eldest daughter of Prince Kuniyoshi Kuni, a lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army, and a member of one of the branch houses of the imperial dynasty entitled to provide a successor to the throne of Japan by adoption. Princess Nagako had been chosen to participate in the tea ceremony because of her lineage and her father’s exemplary military career. The engagement was announced in January 1919, but the marriage did not occur until January 26, 1924.

Hirohito and Nagako in 1924; Credit – Wikipedia

Hirohito and Nagako had seven children. Three daughters, Princess Taka, Princess Yori, and Princess Suga, married commoners and, as required by law instituted after World War II, gave up their imperial titles and left the Japanese Imperial Family.

- Princess Teru (1925 – 1961), married Prince Morihiro Higashikuni, had five children

- Princess Hisa (1927 – 1928), died at five months from an infection

- Princess Taka (1929 – 1989), married Toshimichi Takatsukasa, no children, adopted a son

- Princess Yori (born 1931), married Takamasa Ikeda, no children

- Akihito, Emperor of Japan (born 1933), married Michiko Shōda, had three children, including Naruhito, Emperor of Japan

- Prince Hitachi ( born 1935), married Hanako Tsugaru, no children

- Princess Suga (born 1939), married Hisanga Shimazu, one son

Hirohito and Nagako with five of their children in 1941; Credit – Wikipedia

On December 25, 1926, Emperor Taishō died of a heart attack at the age of 47, and Hirohito began his long reign as Emperor of Japan. The early years of Hirohito’s reign saw an increase in military power in the government by both legal and illegal means. In 1932, the assassination of moderate Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai ended any civilian control of the military. This was followed by the failed coup attempt in Japan on February 26, 1936, by lower-ranking army officers. During the coup, a number of senior government officials and army officers were murdered. The coup finally ended with Hirohito playing an important role.

By the 1930s, the military held almost all of Japan’s political power and pursued policies that eventually led to Japan’s role in World War II. During World War II, Japan formed an alliance with Germany and Italy called the Axis powers. In July 1945, Hirohito wanted to negotiate an end to the war with the Allies. The Allies issued an ultimatum insisting on the unconditional surrender of all Japanese forces and the severe punishment of all Japanese war criminals. The Japanese government did not accept this ultimatum, partly because it was unclear whether Emperor Hirohito would face punishment as a war criminal. On August 6 and August 9, 1945, atomic bombs were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While the Japanese government wished to continue the war, Hirohito decided against the will of the military and government to use his powers and end the war by surrendering.

American General Douglas MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito at their first meeting at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo on September 27, 1945; Credit – Wikipedia

After the war, some believed that Hirohito was chiefly responsible for Japan’s role in the war, and others said that he was just a powerless puppet under the influence of Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō, who was eventually executed for war crimes. The view promoted by the Japanese Imperial Palace and the American occupation forces immediately after World War II portrayed Emperor Hirohito as a powerless figurehead behaving strictly according to protocol. However, since he died in 1989, a debate began to surface over the extent of his involvement and his culpability in World War II.

The Allies insisted that Emperor Hirohito state publicly that he was not a god but just a man like any other. Actually, no emperor had ever claimed that he was a god and so Hirohito made a statement in his usual New Year’s message that did not change the ancient tradition for the Japanese that the Emperor descended from the sun goddess Amaterasu: “Those ties that surround me and my people are not based on the false idea that the Emperor is divine.”

In 1947, a new constitution was enacted with input from the Allies, which replaced Japan’s previous militaristic system of the semi-absolute monarchy with a form of democracy. The constitution provided for a parliamentary system of government and guaranteed certain fundamental rights. Under its terms, the Emperor of Japan is “the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people” and exercises a purely ceremonial role. No amendment has been made to it since its adoption.

Empress Nagako and Emperor Hirohito in 1971; Credit – Wikipedia

For the rest of his life, Emperor Hirohito was an active figure in Japan, performing many of the duties of the head of state. The emperor and his family showed a strong public presence. They often performed official engagements and were seen during special events and holidays. Hirohito also played an important role in rebuilding Japan’s diplomatic position. On foreign trips and in Japan, he met with many foreign heads of state, including Presidents of the United States and Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom.

Empress Nagako, First Lady Betty Ford, Emperor Hirohito, and President Gerald Ford at the White House before a state dinner on October 2, 1975; Credit – Wikipedia

Hirohito was very interested in marine biology, and the Imperial Palace contained a laboratory where he worked. He published several scientific papers on the subject and was considered one of the most respected jellyfish experts in the world.

On September 22, 1987, Emperor Hirohito underwent surgery on his pancreas after several months of digestive problems. The doctors discovered duodenal cancer. Hirohito seemed to recover well after the surgery, but a year later, he collapsed. His health deteriorated, and he suffered from constant internal bleeding. Emperor Hirohito died at the Fukiage Ōmiya Palace on the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, Japan, on January 7, 1989, at the age of 87. He was buried at the Musashi Imperial Graveyard in Hachiōji, Tokyo, Japan, and was given the posthumous name Emperor Shōwa.

Burial Site of Emperor Shōwa; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

State of Japan Resources at Unofficial Royalty

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. (2018). Hirohito. [online] Available at: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hirohito [Accessed 25 Oct. 2018].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Hirohito. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hirohito [Accessed 25 Oct. 2018].

- Ja.wikipedia.org. (2018). 大正天皇. [online] Available at: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A4%A7%E6%AD%A3%E5%A4%A9%E7%9A%87 [Accessed 23 Oct. 2018].