by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2019

King Christian VIII of Denmark; Credit – Wikipedia

Christian VIII was King of Denmark for eleven years, from 1839 to 1848. Christian Frederik was born on September 18, 1786, at Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen, Denmark, the eldest son of Hereditary Prince Frederik of Denmark and Sophia Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Christian’s father was the only child of King Frederik V of Denmark and his second wife Juliana Maria of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. King Christian VII of Denmark, the mentally ill son of King Frederik V of Denmark and his first wife Princess Louisa of Great Britain, was Christian’s half-uncle.

Christian had four siblings:

- Princess Juliana Marie (born and died 1784), died in infancy

- Princess Juliane Sophie (1788 – 1850), married Wilhelm, Landgrave of Hesse-Philippsthal-Barchfeld, no children

- Princess Charlotte (1789 – 1864), married Prince Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel, had six children including Louise who married King Christian IX of Denmark

- Hereditary Prince Ferdinand (1792 – 1863), married Caroline of Denmark, daughter of King Frederik VI of Denmark, no children

Christian had five half-siblings from his father’s first marriage to Princess Louisa of Great Britain, daughter of King George II of Great Britain:

- Prince Christian (1745 – 1747)

- Princess Sophia Magdalena (1746 – 1813) married King Gustav III of Sweden, had issue

- Princess Caroline (1747 – 1820) married Wilhelm I, Elector of Hesse, had issue

- King Christian VII of Denmark and Norway (1749 – 1808) married his first cousin Princess Caroline Matilda of Wales, had issue

- Princess Louise (1750 – 1831) married Prince Karl of Hesse-Kassel, had issue

Christian grew up at Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen. After it was destroyed by fire in 1794, Hereditary Prince Frederick moved his family to Amalienborg Palace. Shortly after the move, Christian’s mother Sophia Frederica died. Christian was just eight years old. Eleven years later, when Christian was nineteen, his father died. Christian received a thorough education from statesman and historian Ove Høegh-Guldberg. He developed an early love for art and science and was exposed to artists and scientists connected to the Danish court. Later in life, Christian served as president of the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen.

During a visit to the court of his maternal uncle Friedrich Franz I, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Christian fell in love with his first cousin Charlotte Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin who was two years younger. Christian and Charlotte Frederica were married at Ludwigslust Palace in Ludwigslust, Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, now in the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, on June 21, 1806.

Charlotte Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, circa 1806; Credit – Wikipedia

Christian and his first wife Charlotte Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Hereditary Princess of Denmark had two sons:

- Christian Friedrich (born and died 1807)

- King Frederik VII of Denmark (1808 – 1863), married (1) Vilhelmine Marie of Denmark, daughter of King Frederik VI of Denmark, no children (2) Caroline Mariane of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, no children (3) Louise Rasmussen, Countess Danner, morganatic marriage, no children

Christian and Charlotte Frederica’s marriage soon became unhappy. Charlotte Frederica had an affair with her singing teacher Édouard Du Puy. In 1809, when Christian found out, Charlotte Frederica was sent into internal exile to the city of Horsens, Denmark while Du Puy was banished from Denmark. The marriage officially ended with a divorce in 1810 and Charlotte Frederica never saw her son again.

Christian as Hereditary Prince of Denmark; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1808, when his half-uncle King Christian VII died, Christian became the heir presumptive to the Danish throne. King Frederik VI, the new king, the only son of King Christian VII, had no surviving sons. Christian needed a new wife and his half-aunt Princess Louise Auguste of Denmark, the only daughter of King Christian VII and also the sister of King Frederik VI, suggested her only daughter Caroline Amalie of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg whose father was Friedrich Christian II, the reigning Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg.

Caroline Amalie of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg; Credit – Wikipedia

In December 1814, Caroline Amalie became engaged to Christian, now Hereditary Prince of Denmark. The couple was married on May 22, 1815, at Augustenborg Palace, Caroline Amalie’s home. After having no success conceiving a child, Christian and Caroline Amalie visited many spas throughout Europe from 1818 – 1822 seeking a cure for their inability to have children. Sadly, the couple remained childless.

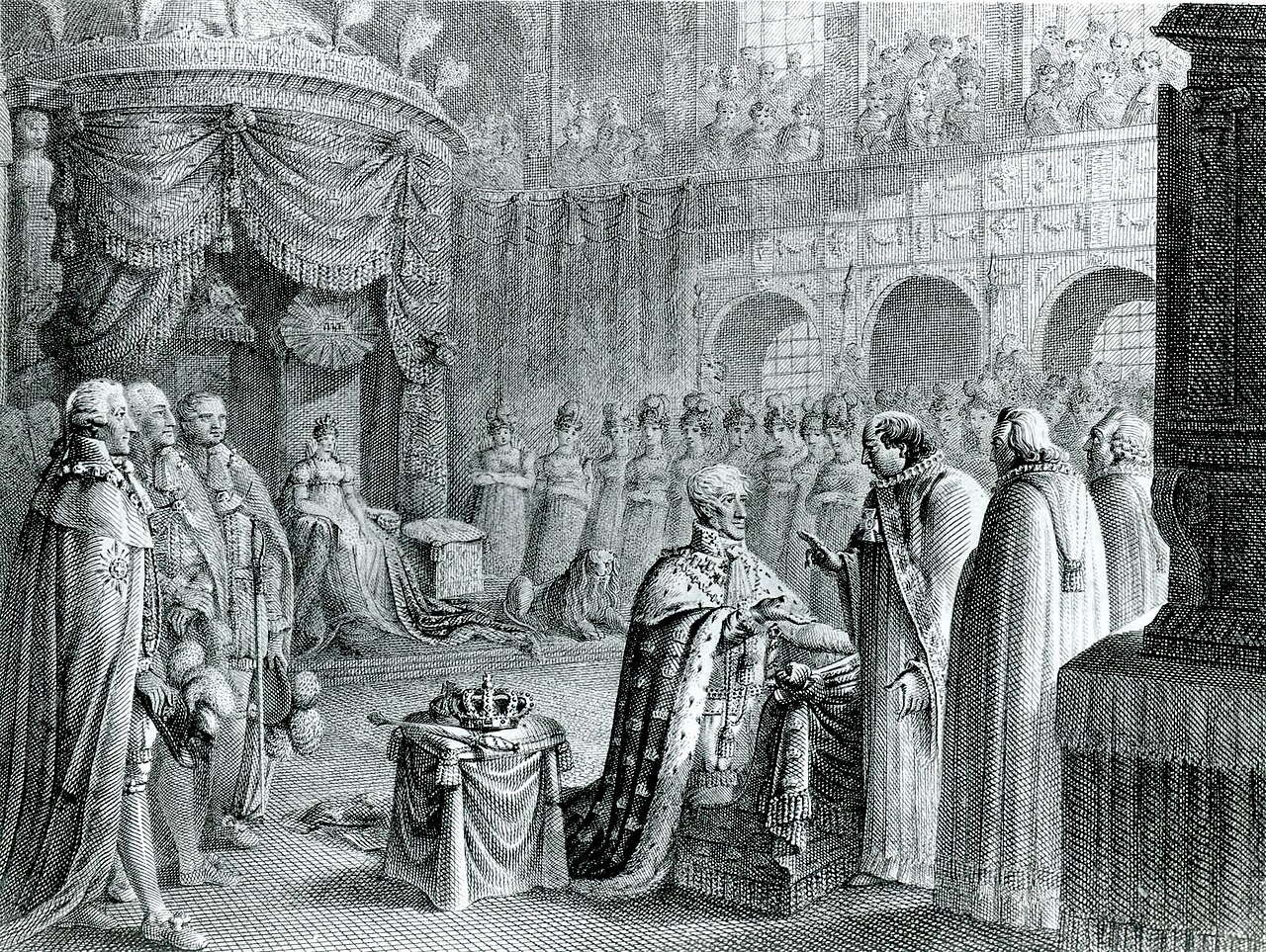

King Frederik VI died on December 3, 1839, and Christian inherited the throne as King Christian VIII. In 1660, the full coronation ritual had been replaced with a ceremony of anointing. On June 28, 1849, Christian VIII’s anointing was held at the Frederiksborg Palace Chapel. He was the last Danish monarch to be anointed.

Anointing of King Christian VIII and Queen Caroline Amalie by Joseph-Désiré Court, 1841; Credit – Wikipedia

During Christian VIII’s reign, the National Liberal Party expected that he would agree with their agenda but the king rejected all of their proposals except administrative reform. The problems in the twin duchies of Schleswig and Holstein continued, with segments of the population identifying with either German or Danish nationality and mobilizing politically.

Christian VIII’s only son, the future King Frederik VII, had been married three times but had no children. Wanting to avert a succession crisis, Christian VIII commenced discussions regarding succession to the throne but the final arrangements would not be completed until the reign of his son.

In December 1847, a month before his death, King Christian VIII commissioned the drafting of a new constitution in which the absolute monarchy would be abolished. He died before the draft was finished and the new constitution would eventually be signed by his son.

On January 20, 1848, at Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen, Denmark 61-year-old King Christian VIII died of blood poisoning after a blood-letting. He was buried at Roskilde Cathedral in the Frederik V Chapel. Christian’s wife Queen Caroline Amalie survived her husband by 33 years, dying on March 9, 1881, at the age of 84.

Tomb of King Christian VIII – Photo by Susan Flantzer

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Kingdom of Denmark Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Kingdom of Denmark Index

- Danish Orders and Honours

- Danish Royal Burial Sites: House of Oldenburg, 1448 – 1863

- Danish Royal Burial Sites: House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, 1863 – present

- Danish Royal Christenings

- Danish Royal Dates

- Danish Royal Residences

- Danish Royal Weddings

- Line of Succession to the Danish Throne

- Profiles of the Danish Royal Family

Works Cited

- Da.wikipedia.org. (2018). Charlotte Frederikke af Mecklenburg-Schwerin. [online] Available at: https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Frederikke_af_Mecklenburg-Schwerin [Accessed 17 Sep. 2018].

- Da.wikipedia.org. (2018). Christian 8.. [online] Available at: https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_8. [Accessed 17 Sep. 2018].

- De.wikipedia.org. (2018). Christian VIII.. [online] Available at: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_VIII. [Accessed 17 Sep. 2018].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Duchess Charlotte Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duchess_Charlotte_Frederica_of_Mecklenburg-Schwerin [Accessed 17 Sep. 2018].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Christian VIII of Denmark. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_VIII_of_Denmark [Accessed 17 Sep. 2018].