by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2019

For christenings of Queen Victoria’s children, her grandchildren who were born British princes and princess, and her other children who were christened in the United Kingdom see Christenings of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, Their Children, and Select Grandchildren.

There is no christening information on King George I, his children King George II and Sophia Dorothea, and the first four children of King George II. All of them were born in Hanover and were most likely christened at Schloss Herrenhausen in Hanover.

********************

King George I, born Georg Ludwig of Brunswick-Lüneburg

King George I as a young army officer; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

CHILDREN OF KING GEORGE I

King George II, born Georg August of Brunswick-Lüneburg

George II, in the middle, with his mother and sister Sophia Dorothea; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Sophia Dorothea of Hanover, Queen of Prussia

(see portrait above)

********************

CHILDREN OF KING GEORGE II

Frederick, Prince of Wales, born Friedrich Ludwig of Brunswick-Lüneburg

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Anne, Princess Royal, Princess of Orange, born Anne of Brunswick-Lüneburg

Anne, Amelia and Caroline, 1721; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Princess Amelia of Great Britain, born Amelia of Brunswick-Lüneburg

(see portrait above)

********************

Princess Caroline of Great Britain, born Caroline of Brunswick-Lüneburg

(see portrait above)

********************

Prince George William of Great Britain

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Prince William, Duke of Cumberland

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Princess Mary of Great Britain, Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Princess Louisa of Great Britain, Queen of Denmark

Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Princess Louisa of Great Britain, Queen of Denmark

- Parents: The Prince of Wales (the future King George II) and Princess of Wales, born, Caroline of Ansbach

- Born: December 18, 1724, at Leicester House in London, England

- Christened: December 22, 1724, at Leicester House in London, England

- Names: Louisa

- Godparents:

- Died: December 19, 1751

********************

CHILDREN AND OF FREDERICK, PRINCE OF WALES

Princess Augusta of Wales, Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

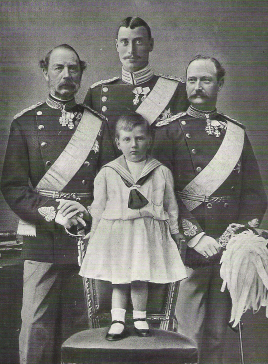

Augusta, on the right, with her brothers George and Edward; Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Princess Augusta of Wales, Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- Parents: Frederick, Prince of Wales and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, Princess of Wales

- Born: July 31, 1737, at St. James’s Palace in London, England

- Christened: September 19, 1737, at St. James’s Palace in London, England

- Names: Augusta Frederica

- Godparents:

- Died: March 23, 1813

********************

King George III of the United Kingdom, born Prince George of Wales

George, on the right, with his brother Edward and their tutor Francis Ayscough; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Prince Edward, Duke of York, born Prince Edward of Wales

(see portrait above)

********************

Princess Elizabeth of Wales

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, born Prince William Henry of Wales

Credit – Wikipedia

- Wikipedia: Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester

- Parents: Frederick, Prince of Wales and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, Princess of Wales

- Born: November 25, 1743, at Leicester House in London, England

- Christened: December 6, 1743, at Leicester House in London, England

- Names: William Henry

- Godparents:

- Died: August 25, 1805

********************

Princess Sophia of Gloucester, daughter of Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester

Credit – Wikipedia

- Wikipedia: Princess Sophia of Gloucester

- Parents: Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Maria Walpole

- Born: May 29, 1773, in Grosvenor Street, Mayfair in London, England

- Christened: June 26, 1773, in the Drawing Room of Gloucester House in Weymouth, England

- Names: Sophia Matilda

- Godparents:

- Prince Henry, Duke of Cumberland, her paternal uncle

- Duchess of Cumberland, her aunt by marriage, born Anne Luttrell

- Queen Caroline Matilda of Denmark, her paternal aunt

(King George III had been asked to be a godfather. However, he refused because he was upset by his brother’s marriage to a commoner. The Royal Marriages Act 1772 were a direct result of the marriages of King George III’s two brothers William Henry and Henry to commoners.)

- Died: November 29, 1844

********************

Princess Caroline of Gloucester, daughter of Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester

********************

Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester, son of Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester

William and his sister Sophia, 1779; Credit – Wikipedia

- Wikipedia: Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester

- Parents: Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Maria Walpole

- Born: January 15, 1776, at Palazzo Teodoli in Via del Corso, Rome

- Christened: February 12, 1776, at Palazzo Teodoli in Via del Corso, Rome

- Names: William Frederick

- Godparents:

- Died: November 30, 1834

(Married his first cousin Princess Mary of the United Kingdom, daughter of King George III)

********************

Prince Henry, Duke of Cumberland, born Prince Henry of Wales

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Princess Louisa of Wales

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Prince Frederick of Wales

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Queen Caroline Matilda of Denmark, born Princess Caroline Matilda of Wales

Caroline Matilda with her mother; Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Caroline Matilda of Wales, Queen of Denmark

- Parents: Frederick, Prince of Wales and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, Princess of Wales

- Born: July 22, 1751, at Norfolk House in St. James’s Square in London, England. Her father died three months before her birth.

- Christened: August 1, 1751, at Norfolk House in St. James’s Square in London, England

- Names: Caroline Matilda

- Godparents:

- Died: May 10, 1775

********************

CHILDREN AND GRANDCHILDREN OF KING GEORGE III

King George IV of the United Kingdom, born George, Prince of Wales

George (left) with his mother and brother Frederick; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Princess Charlotte of Wales, daughter of the future King George IV

Charlotte with her mother; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Prince Frederick, Duke of York

Frederick on the left with his mother and his brother George; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

King William IV of the United Kingdom, William, Duke of Clarence

William (left) and his younger brother Edward, 1778; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Princess Elizabeth of Clarence, daughter of the future King William IV

Recumbent effigy of Princess Elizabeth of Clarence in the Grand Corridor of Windsor Castle, Credit – Wikipedia

- Wikipedia: Princess Elizabeth of Clarence

- Parents: Prince William, Duke of Clarence, the future King William IV and Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen

- Born: December 10, 1820, at St James’ Palace in London, England, six weeks prematurely

- Christened: December 10, 1820, at St James’ Palace in London, England

- Names: Elizabeth Georgiana Adelaide

- Godparents:

- Died: March 4, 1821, of the then inoperable condition of a strangulated hernia. During her short life, Elizabeth was ahead of her cousin, the future Queen Victoria, in the line of succession.

********************

Charlotte, Princess Royal, Queen of Württemberg

Queen Charlotte with Charlotte, Princess Royal; Credit – Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

- Unofficial Royalty: Charlotte, Princess Royal, Queen of Württemberg

- Parents: King George III and Queen Charlotte, born Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Born: September 29, 1766, at Buckingham House (now Buckingham Palace) in London, England

- Christened: October 27, 1766, at St. James’ Palace in London, England

- Names: Charlotte Augusta Matilda

- Godparents:

- Died: October 6, 1828

********************

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

- Parents: King George III and Queen Charlotte, born Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Born: November 2, 1767, at Buckingham House (now Buckingham Palace) in London, England

- Christened: November 30, 1767

- Names: Edward Augustus

- Godparents:

- Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, his paternal uncle by marriage, later Karl II, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- Prince Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, his maternal uncle, later Karl II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel, his paternal great-aunt, born Mary of Great Britain

- Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, his paternal aunt, born Augusta of Wales

- Died: January 23, 1820

********************

Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, born Princess Victoria of Kent, daughter of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Victoria with her mother; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Princess Augusta of the United Kingdom

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Princess Elizabeth, Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg

Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Princess Elizabeth, Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg

- Parents: King George III and Queen Charlotte, born Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Born: May 22, 1770, at the Queen’s House (formerly Buckingham House, now Buckingham Palace) in London, England

- Christened: June 17, 1770, in the Great Council Room at St. James’ Palace in London, England

- Names: Elizabeth

- Godparents:

- Died: January 10, 1840

********************

Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover, Duke of Cumberland

Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover, Duke of Cumberland

- Parents: King George III and Queen Charlotte, born Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Born: June 5, 1771, at the Queen’s House (formerly Buckingham House, now Buckingham Palace) in London, England

- Christened: July 1, 1771, in the Great Council Room at St. James’ Palace in London, England

- Names: Ernest Augustus

- Godparents:

- Died: November 18, 1851

********************

George V, King of Hanover, born Prince George of Cumberland, son of Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover, Duke of Cumberland

Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: George V, King of Hanover

- Parents: Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, later King of Hanover, and Friederike of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Born: May 27, 1819, in a hotel in Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia

- Christened: July 8, 1819, at a hotel in Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia

- Names: George Frederick Alexander Charles Ernest Augustus

- Godparents:

- The Prince Regent, his paternal uncle, the future King George IV

- Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia

- Alexander I, Emperor of All Russia

- Crown Prince of Prussia, the future Friedrich Wilhelm IV, King of Prussia

- Prince Wilhelm of Prussia, the future Wilhelm I, German Emperor and King of Prussia

- Prince Friedrich Ludwig of Prussia

- Prince Heinrich of Prussia

- Prince Wilhelm of Prussia

- Georg, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Duke Charles of Mecklenburg

- Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia, born Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg

- Queen Wilhelmine of the Netherlands, born Wilhelmine of Prussia

- Princess Augusta Sophia of the United Kingdom, his paternal aunt

- Hereditary Princess of Hesse-Homburg, his maternal aunt, born Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom

- Duchess of Gloucester, his maternal aunt, born Princess Mary of the United Kingdom

- Princess Sophia of the United Kingdom, his maternal aunt

- Princess Alexandrine of Prussia

- Electoral Princess of Hesse-Kassel, born Augusta of Prussia

- Duchess of Anhalt-Dessau, born Frederica Wilhelmina of Prussia

- Princess Wilhelm of Prussia, born Marie Anne Amalie of Hesse-Homburg

- Princess Ferdinand of Prussia, born Elisabeth Louise of Brandenburg-Schwedt

- Princess Louisa of Prussia

- Princess Radziwill, born Louise of Prussia

- Died: June 12, 1878

********************

Prince Augustus, Duke of Sussex

Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Prince Augustus, Duke of Sussex

- Parents: King George III and Queen Charlotte, born Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Born: January 27, 1773, at the Queen’s House (formerly Buckingham House, now Buckingham Palace) in London, England

- Christened: February 25, 1773, in the Great Council Room at St. James’ Palace in London, England

- Names: Augustus Frederick

- Godparents:

- Died: April 21, 1843

********************

Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge

Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge

- Parents: King George III and Queen Charlotte, born Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Born: February 24, 1774, at the Queen’s House (formerly Buckingham House, now Buckingham Palace) in London, England

- Christened: February 25, 1773, in the Great Council Room at St. James’ Palace in London, England

- Names: Adolphus Frederick

- Godparents:

- Died: July 8, 1850

********************

Prince George, 2nd Duke of Cambridge, son of Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Princess Augusta of Cambridge, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, daughter of Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge

Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Princess Augusta of Cambridge, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Parents: Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge and Augusta of Hesse-Kassel

- Born: July 19, 1822, at the Palace of Montbrillant in the Kingdom of Hanover where her father was serving as Viceroy of Hanover

- Christened: August 16, 1822, at the Palace of Montbrillant in the Kingdom of Hanover

- Names: Augusta Caroline Charlotte Elizabeth Mary Sophia Louisa

- Godparents:

-

- Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel, her maternal grandmother, born Caroline of Nassau-Usingen

- Princess Luise of Nassau-Usingen, her maternal great-aunt

- Landgravine of Hesse, her maternal aunt by marriage, born Louise of Denmark

- Prince Frederick, Duke of York, her paternal uncle

- Queen Charlotte of Württemberg, her paternal aunt, born Charlotte, Princess Royal

- Princess Augusta Sophia of the United Kingdom, her paternal aunt

- Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg, her paternal aunt, born Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom

- Duchess of Gloucester, her paternal aunt, born Princess Mary of the United Kingdom

- Princess Sophia of the United Kingdom, her paternal aunt

- Electress of Hesse, wife of her mother’s cousin Wilhelm II, Elector of Hesse, born Augusta of Prussia

- Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, her maternal aunt, born Marie of Hesse-Kassel

- Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel, her maternal aunt by marriage, born Louise Charlotte of Denmark

- Died: December 5, 1916

********************

Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, Duchess of Teck, daughter of Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge

Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, Duchess of Teck

- Parents: Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge and Augusta of Hesse-Kassel

- Born: November 27, 1833, at Cambridge House in the Kingdom of Hanover where his father was serving as Viceroy of Hanover

- Christened: January 9, 1834, at the Palace of Montbrillant in the Kingdom of Hanover

- Names: Mary Adelaide Wilhelmina Elizabeth

- Godparents

- King William IV, her paternal uncle

- Queen Adelaide, her paternal aunt by marriage, born Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen

- Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester, her paternal aunt

- Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, her maternal aunt, born Princess Marie of Hesse-Kassel

- Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg, her paternal aunt, born Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom

- Princess Friedrich Augustus of Anhalt-Dessau, her maternal first cousin, born Princess Marie of Hesse-Kassel

- Died: October 26, 1897

(Mary Adelaide was the mother of Queen Mary, the wife of King George V of the United Kingdom)

********************

Princess Mary of the United Kingdom, Duchess of Gloucester

Credit – Wikipedia

- Unofficial Royalty: Princess Mary of the United Kingdom, Duchess of Gloucester

- Parents: King George III and Queen Charlotte, born Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Born: April 25, 1776, at the Queen’s House (formerly Buckingham House, now Buckingham Palace) in London, England

- Christened: May 19, 1776, in the Great Council Room at St. James’ Palace in London, England

- Names: Mary

- Godparents:

- Died: April 30, 1857

********************

Princess Sophia of the United Kingdom

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

Prince Octavius of Great Britain

Credit – Wikipedia

Note: Prince Octavius is “of Great Britain” because it was not until 1801, after his death, that his father’s title changed to “of the United Kingdom.”

- Unofficial Royalty: Prince Octavius of Great Britain

- Parents: King George III and Queen Charlotte, born Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Born: February 23, 1779, at the Queen’s House (formerly Buckingham House, now

- Buckingham Palace) in London, England

- Christened: March 23, 1779, in the Great Council Room at St. James’ Palace in London, England

- Names: Octavius

- Godparents:

- Died: May 3, 1783, less than two months his fourth birthday, after a smallpox immunization

********************

Prince Alfred of Great Britain

Credit – Wikipedia

Note: Prince Alfred is “of Great Britain” because it was not until 1801, after his death, that his father’s title changed to “of the United Kingdom.”

- Unofficial Royalty: Prince Alfred of Great Britain

- Parents: King George III and Queen Charlotte, born Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Born: September 22, 1780, at the Queen’s House (formerly Buckingham House, now Buckingham Palace) in London, England

- Christened: October 21, 1780, in the Great Council Room at St. James’ Palace in London, England

- Names: Octavius

- Godparents:

- Died: August 20, 1782, a month short of his second birthday, after a smallpox immunization

********************

Princess Amelia of the United Kingdom

Credit – Wikipedia

********************

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.