by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2018

Coronet of a son or daughter of a sovereign; Credit – By SodacanThis W3C-unspecified vector image was created with Inkscape. – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10963941

There are articles about most of the people mentioned here (and lots more!) at British Index.

Derivation of Words Prince and Princess

Prince and its female equivalent Princess come from the Latin word prīnceps, meaning the one who takes the first place or position. The title of the leader of the Senate in ancient Rome was the princeps senatus.

prince – noun – a non-reigning male member of a royal family

Origin of the word prince – first used in Middle English 1175-1225; from Anglo-Norman prince, from Old French prince, from Latin prīnceps (“first head”), from prīmus (“first”) + capiō (“seize, take”).

princess – noun – a non-reigning female member of a royal family

Origin of the word princess – first used in Middle English 1350-1400; from Anglo-Norman princesse, from Old French princesse

-ess – a suffix forming distinctively feminine nouns; since at least the 14th century, English has borrowed feminine nouns ending in -ess from French

Origin of the suffix – ess, from Middle English, from Old French -esse, from Late Latin -esse, from Greek -issa

from https://www.dictionary.com, https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/prince, and https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/princess#English

*********************

History

Edward, Prince of Wales (the Black Prince) as Knight of the Order of the Garter, illustration from the Bruges Garter Book 1453; Edward never became King as he predeceased his father King Edward III; Credit – Wikipedia

The formal use of the titles prince and princess and the styles of Royal Highness for members of the British royal family is of fairly recent origin. In the past, children of kings were often identified by their birthplace: King Edward II’s daughter Joan of the Tower was born at the Tower of London and King Edward III’s son Lionel of Antwerp was born in Antwerp (now in Belgium) due to his parents’ long stay in the Low Countries due to the Hundred Years War. Usually, when sons of kings became older, they received peerages. For instance, Lionel of Antwerp was created Duke of Clarence when he was twenty years old. Frequently, daughters of kings were called “Lady” or “The Lady” followed by their first name. Although Prince and Princess were sometimes used, it was not a consistent practice.

From 1301, the heir apparent of the Kings of England (and later Great Britain and the United Kingdom) has generally been created Prince of Wales. Their wives were styled Princess of Wales. In 1642, Mary, the eldest daughter of King Charles I, was created the first Princess Royal. Her mother Queen Henrietta Maria, daughter of King Henri IV of France, wanted to imitate the way the eldest daughter of the King of France was styled Madame Royale. Holders retain the style for life, so a princess cannot receive the style during the lifetime of another Princess Royal. There will be separate articles dealing with the titles Prince of Wales and Princess Royal.

In 1714, when Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hanover and Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg came to the British throne as King George I, the first monarch of the House of Hanover, princely titles and styles began to follow the German practice. The children, grandchildren, and male-line great-grandchildren of the British sovereign were automatically titled Prince or Princess of Great Britain and Ireland. Children and grandchildren of the British sovereign were styled Royal Highness and male-line great-grandchildren were styles Highness.

*********************

Current Styles of Princes (using current or recent examples)

The Prince of Wales and The Duke of Sussex; Credit – Wikipedia

Examples (HRH = His Royal Highness)

- Sovereign’s heir apparent if Prince of Wales: HRH The Prince of Wales

- The Prince of Wales’ sons without a peerage: HRH Prince George of Wales

- Sovereign’s sons with a peerage (not Prince of Wales): HRH The Duke of York

- Sovereign’s sons without a peerage: HRH The Prince John

- Sovereign’s male-line grandsons with a peerage: HRH The Duke of Kent

- Sovereign’s male-line grandsons without a peerage: HRH Prince Michael of Kent (territorial designation of their father’s senior peerage)

- Sons of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales: HRH Prince George of Cambridge – before his father became Prince of Wales (territorial designation of their father’s senior peerage)

Current Princes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Current Styles of Princess (using current or recent examples)

The Princess Royal, Princess Beatrice, Mrs. Edoardo Mapelli Mozzi; Credit – Wikipedia

Only a princess in her own right – a Sovereign’s daughter, The Prince of Wales’ daughter, a Sovereign’s male-line granddaughter, and a daughter of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales – may use Princess followed by her first name:

When a princess marries, she takes on her husband’s title: HRH The Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon or HRH Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone. However, some of the lower styles are not used by senior royals. For instance, Princess Anne remains HRH The Princess Royal rather than HRH The Princess Royal, Lady Laurence. If a married princess had a territorial designation, she stops using it upon marriage: Princess Alexandra of Kent was styled Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Mrs. Angus Ogilvy upon her marriage.

Examples (HRH = Her Royal Highness)

- Sovereign’s eldest daughter: HRH The Princess Royal (usually, but not automatically, granted by the Sovereign, when the previous Princess Royal is no longer living)

- Sovereign’s daughter: HRH The Princess Margaret

- The Prince of Wales’ daughter: HRH Princess Charlotte of Wales

- Sovereign’s male-line granddaughter: HRH Princess Beatrice of York (before her marriage, territorial designation of their father’s senior peerage)

- Daughters of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales: HRH Princess Charlotte of Cambridge (before her father was Prince of Wales, territorial designation of their father’s senior peerage)

A woman who marries a Prince does not become a Princess in her own right. It is incorrect to use the title Princess followed by the wife’s first name. For example, Princess Diana and Princess Meghan are incorrect.

After marrying The Prince of Wales in 2005, the former Camilla Parker-Bowles automatically received the female counterparts of her husband’s titles, including Princess of Wales. However, because the title Princess of Wales was so strongly associated with the previous holder of that title, Diana, Princess of Wales, Camilla adopted the feminine form of her husband’s highest-ranking subsidiary title, Duke of Cornwall, so she was styled Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cornwall. When in Scotland, she was known as The Duchess of Rothesay – more about the Duke of Rothesay in a separate article.

- Wife of The Prince of Wales: HRH The Princess of Wales

- Wife of a prince who has a peerage: HRH The Duchess of Sussex

- Wife of a son of a Sovereign who has no peerage: HRH The Princess Edward would be HRH The Duchess of Edinburgh’s style if her husband did not have a peerage

- Wife of a prince who has no peerage: HRH Princess Michael of Kent (territorial designation of the father of their husband)

- Divorced wife of a prince who has a peerage: Diana, Princess of Wales and Sarah, Duchess of York (according to a 1996 Letters Patent, divorced wives are no longer entitled to use the style Her Royal Highness)

Current Princesses of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

*********************

General Letters Patent and Proclamations Regarding Titles and/or Styles

“A Good Riddance”; cartoon from Punch, Vol. 152, 27 June 1917, commenting on King George V’s order to relinquish all German titles held by members of his family; Credit – Wikipedia

Although Letters Patent, Warrants and Proclamations are sometimes issued when titles and styles are changed, it is not necessary. Royal styles and titles are a matter of royal prerogative. At the Sovereign’s will and pleasure, styles and titles can be changed as the Sovereign pleases. Letters Patent tend to be encompassing. For instance, in 2012, Queen Elizabeth II issued a Letters Patent declaring that all the children of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales should have the title Prince or Princess and the style Royal Highness – not a Letters Patent stating that children of Prince William will be HRH Prince/Princess.

The links below lead to the actual text of each document.

Children of sons of the Sovereign (January 30, 1864): Three weeks after the birth of Prince Albert Victor of Wales, Queen Victoria’s first male-line grandson, she issued Letters Patent which formally confirmed the practice of styling children and male-line grandchildren of the Sovereign His/Her Royal Highness Prince/Princess. However, the Letters Patent did not mention the styling of great-grandchildren as His/Her Highness or Prince or Princess.

Letters Patent: Children of sons of the Sovereign (January 30, 1864)

Children of the eldest son of any Prince of Wales (May 28, 1898): The children of Prince George, Duke of York, the eldest living son of the Prince of Wales, were titled Prince/Princess with the style of Highness, as great-grandchildren of Queen Victoria in the male-line. Queen Victoria issued Letters Patent which granted all children of the eldest son of any Prince of Wales the style and title of Royal Highness Prince/Princess.

Letters Patent: Children of the eldest son of any Prince of Wales (May 28, 1898)

German titles (July 17, 1917): King George V issued a royal proclamation changing the name of the Royal House from the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to the House of Windsor and ordering the relinquishment of the German titles Duke of Saxony, Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and other German titles.

Proclamation: German titles (July 17, 1917)

Titles Deprivation Act 1917 (November 8, 1917): The Titles Deprivation Act 1917 is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom which authorized enemies of the United Kingdom during World War I to be deprived of their British peerages and royal titles. The Act contained specific procedures to identify British peers or British princes who had “borne arms against His Majesty or His Allies, or who have adhered to His Majesty’s enemies.” A report naming such persons would be sent to both Houses of Parliament. If neither House passed a motion disapproving of the report within forty days, the report would be sent to the King and the persons named would be deprived of their British peerages and/or British royal titles. A successor of a peer or a prince deprived of titles could petition for the restoration of the titles. So far, no successor has petitioned for a title to be restored.

Titles Deprivation Act (1917)

In 1919, four people were deprived of their British peerages and/or titles:

- His Royal Highness Charles Edward, Duke of Albany, Earl of Clarence and Baron Arklow (also previously reigning Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, grandson of Queen Victoria)

- His Royal Highness Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale, Earl of Armagh (also previously reigning Duke of Brunswick, great-grandson of King George III)

- His Royal Highness Ernest Augustus, Prince of Great Britain and Ireland (also previously Hereditary Prince of Brunswick, son and heir-apparent of the Duke of Cumberland)

- Henry Taaffe, Viscount Taaffe of Corren and Baron of Ballymote

Members of the Royal Family (November 30, 1917): King George V issued Letters Patent changing the rights to the style Royal Highness and the title Prince/Princess. The children of the Sovereign, the children of the sons of the Sovereign, and the eldest living son of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales would be entitled to the style Royal Highness and the title Prince/Princess. The Letters Patent also stipulated that the styles Royal Highness, Highness or Serene Highness and the title Prince or Princess should not be used by any descendent of any Sovereign. Grandchildren of the sons of the Sovereign in the direct male-line are entitled to the style and title enjoyed by the children of Dukes: Lord/Lady followed by their first name and surname.

Letters Patent: Members of the Royal Family (November 30, 1917)

Former Wives (August 21, 1996): Queen Elizabeth II issued a Letters Patent stating that a former wife (other than a widow until she shall remarry) of a son of a Sovereign, a son of a son of a Sovereign, and the eldest living son of the eldest son of The Prince of Wales shall not be entitled to the style of Royal Highness.

Letters Patent: Former Wives (August 21, 1996)

Children of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales (December 31, 2012): Queen Elizabeth II issued a Letters Patent declaring that all the children of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales should have the title Prince or Princess and the style Royal Highness.

Letters Patent: Children of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales (December 31, 2012)

*********************

Exceptions to the Rule

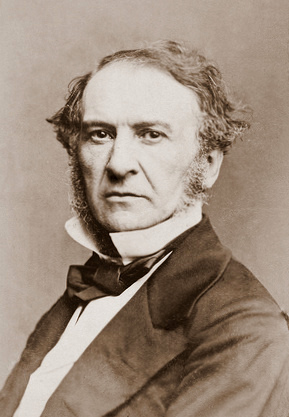

Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria was granted the style His Royal Highness upon his marriage in 1840 and the title Prince Consort in 1857; Credit – Wikipedia

The links below lead to the actual text of each document.

Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh (July 22, 1816): As a male-line great-grandchild of King George II, he was styled His Highness. In 1816, when he married Her Royal Highness Princess Mary, his cousin and daughter of King George III, he was granted the style His Royal Highness by his uncle The Prince Regent. His only surviving sibling, Princess Sophia of Gloucester, was also granted the style Her Royal Highness at the same time.

Warrant: 2nd Duke of Gloucester (July 22, 1816)

Warrant: Princess Matilda of Gloucester (July 22, 1816)

Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Saalfeld (April 6, 1818): Upon his marriage to Princess Charlotte of Wales in 1818, The Prince Regent granted him the style His Royal Highness.

Warrant: Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (April 6, 1818)

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (February 6, 1840): Upon his marriage to Queen Victoria in 1840, he was granted the style His Royal Highness.

Warrant: Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (February 6, 1840)

Prince Albert (June 29, 1857): Queen Victoria granted her husband the title Prince Consort in 1857. He is the only husband of an English or British Queen Regnant to have that title.

Letters Patent: Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (June 29, 1857)

Prince Ludwig of Hesse (June 29, 1866): Queen Victoria granted Prince Ludwig of Hesse, the future Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine, the style of His Royal Highness when he married her daughter Princess Alice in 1862.

Warrant: Prince Louis of Hesse (July 5, 1862)

Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein: Queen Victoria granted Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, the style of His Royal Highness when he married her daughter Princess Helena in 1866.

Warrant: Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (June 29, 1866)

Children of Prince and Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (May 15, 1867): Through Her Royal Will and Pleasure, Queen Victoria declared that the children of her daughter Princess Helena and her husband Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein would be British-born subjects and descendants of her Royal House and have the style of Highness prefixed to their respective Christian names. As male-line grandchildren of the Duke of Schleswig-Holstein, the children of Princess Helena and her husband Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein would have been styled His/Her Serene Highness. Highness is considered a higher ranking than Serene Highness.

Children of Prince and Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (May 15, 1867)

Prince Henry of Battenberg (July 22, 1885): Queen Victoria granted Prince Henry of Battenberg the style of His Royal Highness when he married her daughter Princess Beatrice in 1885.

Warrant: Prince Henry of Battenberg (July 22, 1885)

Children of Prince and Princess Henry of Battenberg (December 4, 1886): Through Her Royal Will and Pleasure, Queen Victoria declared that the children of her daughter Princess Beatrice and her husband Prince Henry of Battenberg would be British-born subjects and descendants of her Royal House and have the style of Highness prefixed to their respective Christian names. The children of Princess Beatrice and Prince Henry of Battenberg would have used their father’s style His/Her Serene Highness. Highness is considered a higher ranking than Serene Highness.

Children of Prince and Princess Henry of Battenberg (December 4, 1886) (scroll up a bit)

Francis, Duke of Teck (July 1, 1887): Francis, Duke of Teck married Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, granddaughter of King George III and first cousin of Queen Victoria. He had been styled His Serene Highness. Queen Victoria granted the Duke of Teck the style of Highness as a gift to celebrate her Golden Jubilee. Francis and Mary Adelaide were the parents of Princess Victoria Mary of Teck, better known as Queen Mary, wife of King George V.

Warrant: Duke of Teck (July 1, 1887)

Daughters of The Princess Royal (November 9, 1905): In 1889, Prince Louise of Wales, elder daughter of the future King Edward VII, married Alexander Duff, 1st Duke of Fife. The couple had two daughters, Alexandra and Maud. As female-line great-granddaughters of the British monarch, (Queen Victoria), Alexandra and Maud were not entitled to the title of Princess or the style Royal Highness. Instead, they were styled Lady Alexandra Duff and Lady Maud Duff, the styles of daughters of a Duke.

In 1900, when it became apparent that the Duke and Duchess of Fife were unlikely to have a son to inherit the title, Queen Victoria issued the Duke of Fife a new Letters Patent as Duke of Fife and Earl of Macduff in the Peerage of the United Kingdom giving the second dukedom of Fife a special remainder in default of male issue to the Duke’s daughters and their male descendants. Upon the death of the Duke of Fife, his daughter Alexandra succeeded him as Duchess of Fife in her own right.

Louise was the eldest daughter of King Edward VII and was created Princess Royal during her father’s reign, in 1905. At the same time, King Edward VII granted Louise’s daughters Alexandra and Maud the title of Princess with the style of Highness.

The Princess Royal and her daughters (November 9, 1905)

Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg (April 3, 1906): In 1886, Queen Victoria declared that the children of her daughter Princess Beatrice and her husband Prince Henry of Battenberg would be British-born subjects and descendants of her Royal House and have the style of Highness. In 1906, Her Highness Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg was to marry King Alfonso XIII of Spain. Although one of Victoria Eugenie’s brothers had hemophilia, the bigger obstacles were her Anglican religion and, as far as Alfonso’s mother was concerned, her less-than-royal bloodline. The princess willingly agreed to convert to Catholicism, and her uncle King Edward VII elevated her rank to Royal Highness so there could be no question of an unequal marriage.

Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg (April 3, 1906)

Adolphus, Duke of Teck (June 9, 1911): Adolphus, Duke of Teck was the brother of Queen Mary, wife of King George V. He had been styled His Serene Highness. On June 9, 1911, King George V granted his brother-in-law the style His Highness as a gift to mark the King’s coronation.

Warrant: 2nd Duke of Teck (June 9, 1911)

Children of Ernst August, Duke of Brunswick (June 17, 1914): In 1914, shortly after the birth of Ernst August, Hereditary Prince of Brunswick, the eldest child of Ernest Augustus, Duke of Brunswick, King George V granted the children of the Duke and Duchess of Brunswick the style Highness and declared that they would be Prince or Princess of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Ernst August, Duke of Brunswick was a grandson of King George III’s son Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, who succeeded to the throne of the Kingdom of Hanover in 1837, when Queen Victoria became the British monarch. Hanover did not allow for female succession and so the eldest surviving son of King George III became King of Hanover.

Letters Patent: Children of Ernst August, Duke of Brunswick (June 17, 1914)

Lady Patricia Ramsay (February 25, 1919): In 1919, Princess Patricia of Connaught, male-line granddaughter of Queen Victoria, married The Honorable Alexander Ramsay, the third son of John Ramsay, 13th Earl of Dalhousie. Upon her marriage, Princess Patricia voluntarily relinquished the style of Royal Highness and the title of Princess of Great Britain and Ireland and assumed the style of Lady Patricia Ramsay. However, Lady Patricia remained a member of the British Royal Family, remained in the line of succession, and attended all major royal events including weddings, funerals, and the coronations. Her first cousin King George V issued a warrant allowing Princess Patricia to relinquish her style and title upon her marriage.

Warrant: Lady Patricia Ramsay (February 25, 1919)

Duke of Windsor (May 27, 1937): After King Edward VIII abdicated in 1936, his brother and successor King George VI issued Letters Patent regranting his brother his style His Royal Highness, as a son of a Sovereign. However, his brother’s wife and any descendants were denied the style Royal Highness. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor’s marriage was childless.

Letters Patent: Duke of Windsor (May 27, 1937)

Duke of Edinburgh (November 19, 1947): Upon the marriage of his daughter Princess Elizabeth and Lt. Philip Mountbatten, King George VI issued Letters Patent granting his daughter’s husband the style His Royal Highness and the peerage Duke of Edinburgh.

Letters Patent: Duke of Edinburgh (November 19, 1947)

Children of HRH The Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh (October 22, 1948): Just prior to the birth of the first child of Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh, King George VI issued Letters Patent declaring that their children have the style Royal Highness and the titles Prince or Princess. Without this Letters Patent, their children would have been styled as the children of a Duke: Charles Mountbatten, Earl of Merioneth and The Lady Anne Mountbatten.

Letters Patent: Children of HRH The Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh (October 22, 1948)

Duke of Edinburgh (February 22, 1957): Queen Elizabeth II issued Letters Patent creating her husband the Duke of Edinburgh, a Prince of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Before his marriage, Philip relinquished his Greek and Danish royal titles, adopted the surname Mountbatten from his mother’s family, and became a naturalized British subject.

Letters Patent: Duke of Edinburgh (February 22, 1957)

Duchess of Kent (1961): When her son Prince Edward, Duke of Kent married in 1961, the Duchess of Kent asked Queen Elizabeth II permission to be styled Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent to avoid confusion with her daughter-in-law Katherine Worsley, the new Duchess of Kent. Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent had been born Her Royal Highness Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark.

Duchess of Gloucester (1974): In 1974, after the death of her husband, the Duchess of Gloucester received permission from Queen Elizabeth II to style herself Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester to distinguish herself from her son’s wife, the new Duchess of Gloucester. Unlike Princess Marina, Alice had been born Lady Alice Montagu Douglas Scott and had never been a princess in her own right, and so allowing this was far more unusual.

The children of the Earl of Wessex (June 19, 1999): At the time of the wedding of Prince Edward, Queen Elizabeth II’s youngest child, and Sophie Rhys-Jones, it was announced that Queen Elizabeth II had decided, in agreement with the wishes of Prince Edward and Miss Rhys-Jones, that any children of their marriage would not be given the style Royal Highness and the title Prince or Princess. Instead, any children would have courtesy titles of sons or daughters of an Earl. No Letters Patent was issued. However, royal styles and titles are a matter of royal prerogative. At the Sovereign’s will and pleasure, styles and titles can be changed as the Sovereign pleases.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

*********************

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). British prince. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_prince [Accessed 30 Nov. 2018].

- Velde, F. (2018). Royal Styles and Titles of Great Britain: Documents. [online] Heraldica.org. Available at: https://www.heraldica.org/topics/britain/prince_highness_docs.htm [Accessed 30 Nov. 2018].