by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2018

Besides being the Sovereign King or Queen, the English and British sovereigns had other titles over the years. One of the titles, Duke of Lancaster, will be explored in a separate article.

Duke of Normandy

Map of France in 1154; Credit – By Reigen – Own work.Sources :Image:France 1154 Eng.jpg by Lotroo under copyleftfrance_1154_1184.jpg from the Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1911., CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37306574

- Duke of Normandy: William I, William II, Henry I, Stephen, Henry II, Richard I, John, Henry III

The Duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in northwest France. The duchy originated when King Charles III of West Francia granted land to the Viking leader Rollo in 911. In 1035, a young boy succeeded his father as William II, Duke of Normandy. William was the first cousin once removed of Edward the Confessor, King of the English. Edward the Confessor’s mother Emma of Normandy was the sister of William’s grandfather Richard II, Duke of Normandy. William’s marriage to Matilda of Flanders may have been motivated by his growing desire to become King of England. Matilda was a direct descendant of Alfred the Great, King of Wessex. In 1051, William visited his first cousin once removed, Edward the Confessor, King of England, and apparently Edward named William as his successor.

In 1065, Edward the Confessor, King of the English died and Harold Godwinson was selected to succeed Edward as King Harold II. When William heard that Harold Godwinson had been crowned King of the English, he began preparations for an invasion of England. At the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066, the army of William II, Duke of Normandy won the battle and King Harold II was killed. On Christmas Day 1066, William, Duke of Normandy was crowned William I, King of the English at Westminster Abbey.

In 1202, during the reign of King John, King Philippe II of France confiscated the Duchy of Normandy and by 1204, the French army had conquered it. King Henry III continued to use the title until 1259 when he renounced it in the Treaty of Paris (1259).

Count of Anjou (see map above)

- Count of Anjou: Henry II, Richard I

The Count of Anjou was the ruler of the County of Anjou in northwest France. The future King Henry II became Count of Anjou upon the death of his father Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou in 1151. Three years later, he became King of the English upon the death of his mother’s cousin King Stephen of England. When King Richard I of England died childless in 1199, the title was inherited by his nephew Arthur, Duke of Brittany, the son of his deceased brother Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany. However, in 1204, Anjou was lost to King Philippe II of France.

Duke of Aquitaine (see map above)

- Duke of Aquitaine: Henry II, Richard I, John, Henry III, Edward I, Edward II, Edward III

The Duke of Aquitaine was the ruler of the Duchy of Aquitaine in western, central, and southern areas of France. It was a duchy that women could inherit and manage independently from their husbands or male relations and that is how it came into the English royal family. Eleanor of Aquitaine, wife of King Henry II, was the Duchess of Aquitaine, Countess of Poitiers and Duchess of Gascony in her own right. When Henry II became King of the English in 1153, Eleanor’s possessions merged with the English crown.

In 1337, King Philippe VI of France claimed Aquitaine from King Edward III of England. Edward III then claimed the title of King of France, by right of his descent from his maternal grandfather King Philippe IV of France. This started the Hundred Years’ War, in which the House of Plantagenet and the House of Valois fought over the control of the territories in France.

Lord of Ireland

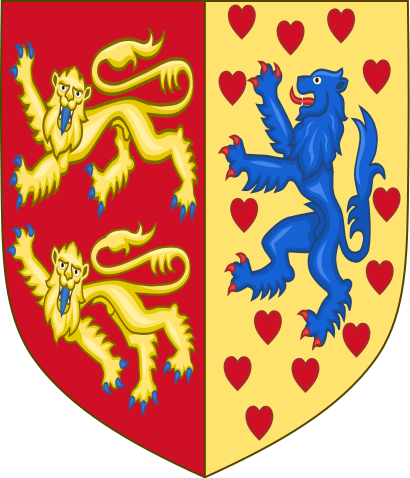

Arms of the Lordship of Ireland; Credit – Wikipedia

- Lord of Ireland: John, Henry III, Edward I, Edward II, Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI, Edward IV, Edward V, Richard III, Henry VII, Henry VIII

An invasion of Ireland starting in 1169 by King Henry II eventually brought about the end of the rule of the High Kings of Ireland and the direct involvement of the English/British in Irish politics until 1922. In 1177, King Henry II gave the part of Ireland he controlled at that time to his ten-year-old son John as the Lordship of Ireland and John became Lord of Ireland. When John succeeded to the English throne in 1199, he remained Lord of Ireland, bringing the Kingdom of England and the Lordship of Ireland into personal union. The title of Lord of Ireland was abolished by King Henry VIII of England who was made King of Ireland by the Parliament of Ireland by the Crown of Ireland Act 1542.

King/Queen of France

Edward III quartered the Royal Arms of England with the ancient arms of France, the fleurs-de-lis on a blue field, to signal his claim to the French throne; Credit – Wikipedia

- King/Queen of France: Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI, Henry VI, Edward IV, Edward V, Richard III, Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, Lady Jane Grey (disputed), Mary I, Elizabeth, James I, Charles I, Charles II, James II, William III and Mary II, Anne, George I, George II, George III

The Kings and Queens of England and Great Britain listed above were never really sovereigns of France. From 1337 to 1801, the Kings and Queens of England and Great Britain claimed the throne of France.

In 1337, King Edward III of England claimed the title of King of France, by right of his descent from his maternal grandfather King Philippe IV of France. This started the Hundred Years’ War fought from 1337 to 1453 by the English House of Plantagenet against the French House of Valois over the right to rule the Kingdom of France. By the time the war was over, France had achieved a victory and England permanently lost all of its French possessions except the Pale of Calais. The Pale of Calais remained under English control until it was lost to France in 1558 during the reign of Queen Mary I of England, who reportedly said: “When I am dead and opened, you shall find ‘Calais’ written on my heart.

Despite having no territory in France, the English and British monarchs continued to call themselves Kings/Queens of France and the French fleurs-de-lis was included in the royal arms. The French Revolution had abolished the monarchy in 1792 and replaced it with the French First Republic. The French government demanded that the King of Great Britain relinquish the title of King of France. In 1801, King George III decided to drop his claim to the French throne and the fleurs-de-lis was removed from the British royal arms.

King/Queen of Ireland

Ancient Royal Arms of the Kingdom of Ireland, as first used by the monarchs of the Kingdom of England; Credit – Wikipedia

- King/Queen of Ireland: All sovereigns from King Henry VIII to King George V (1542 – 1927)

The Crown of Ireland Act 1542 was an act of the Irish Parliament replacing the Lordship of Ireland, which had existed since 1177, with the Kingdom of Ireland. The title changed from Lord of Ireland to King of Ireland. This was a personal union between t.he English and Irish crowns and whoever was King of England was to be King of Ireland as well. The first King of Ireland was King Henry VIII of England. In 1922, the Irish Free State, now the Republic of Ireland, became independent. Today’s Northern Ireland still remains part of the United Kingdom.

Defender of the Faith

- Defender of the Faith: All sovereigns from King Henry VIII to the present sovereign

In 1521, a theological treatise called The Defense of the Seven Sacraments was published. It was written by King Henry VIII of England, supposedly with the assistance of Sir Thomas More, and it defended the Roman Catholic Church’s seven sacraments and the supremacy of the Pope. This treatise was an important opposition to the Protestant Reformation, especially Martin Luther, one of the Reformation’s chief proponents. In recognition of the treatise, Pope Leo X granted King Henry VIII the title Defender of the Faith (Fidei Defensor in Latin).

In 1530, King Henry VIII decided to break away from the Roman Catholic Church and establish himself as head of the Church of England. Since Henry VIII’s decision was considered an attack on “the Faith”, Pope Paul III revoked the title Defender of the Faith and excommunicated Henry VIII.

In 1544, the Parliament of England conferred the title “Defender of the Faith” on King Henry VIII and his successors. Now they were defenders of the Protestant Anglican faith (Church of England) except for Henry VIII’s daughter, Queen Mary I, who was Catholic.

Supreme Head/Supreme Governor of the Church of England

- Supreme Head of the Church of England: Henry VIII, Edward VI, Lady Jane Grey, Mary I

- Supreme Governor of the Church of England: Elizabeth I to the present sovereign

The Supreme Head of the Church of England was a title created in 1531 for King Henry VIII of England. The Act of Supremacy of 1534 confirmed Henry VIII’s status as Supreme Head of the Church of England and granted the same status to subsequent sovereigns. Henry VIII’s Roman Catholic daughter Queen Mary I of England attempted to restore the Roman Catholic Church and repealed the Act of Supremacy in 1555.

After Mary I’s death in 1558, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy 1558 which restored the original act. The act also changed the sovereign’s title to Supreme Governor of the Church of England. This change avoided the charge that the sovereign was claiming to be divine and negating that the New Testament says that Jesus Christ is the Head of the Church. All sovereigns from Queen Elizabeth I to the present sovereign have been the Supreme Governor of the Church of England.

King/Queen of Scots

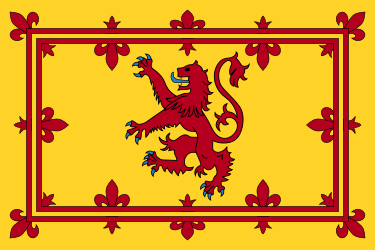

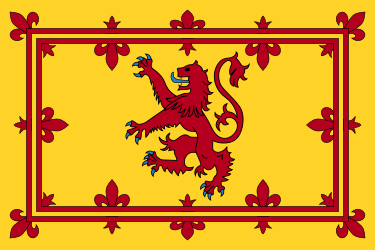

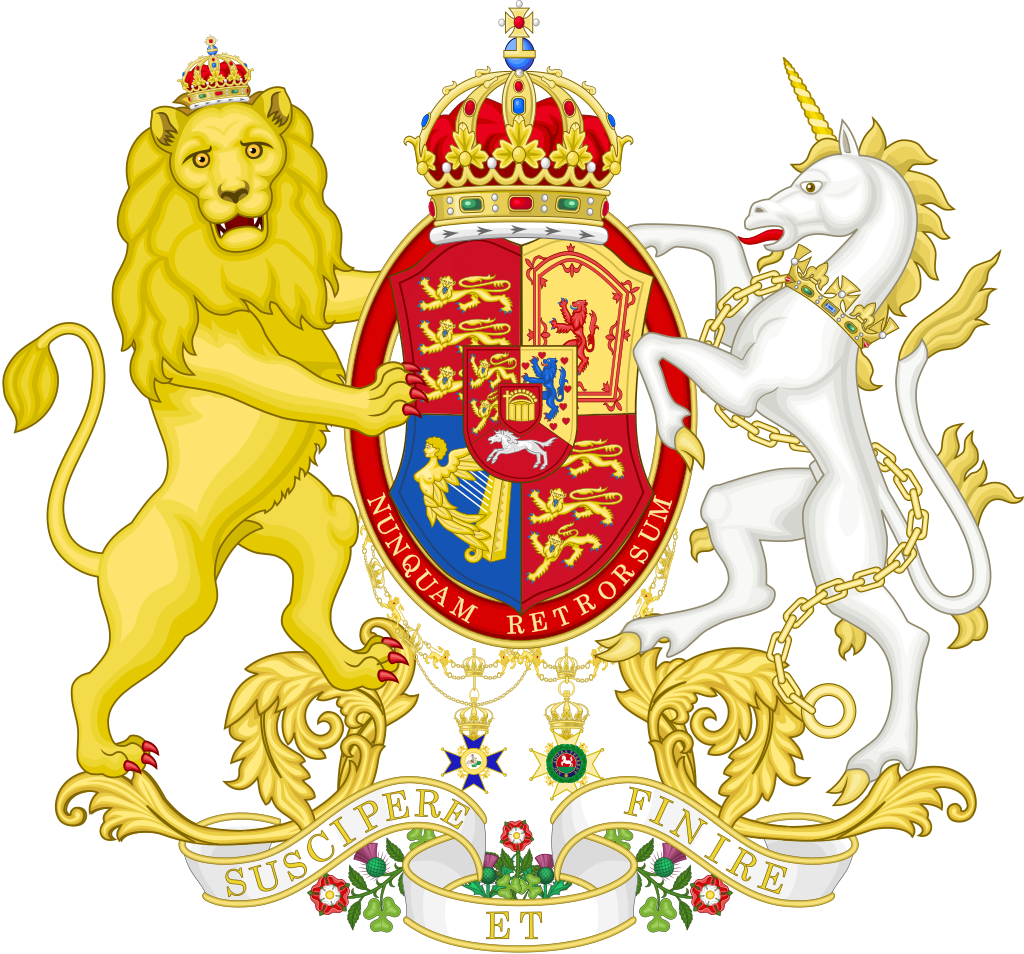

Royal Standard of the King of Scots; Credit – Wikipedia

- King/Queen of Scots: James I as James VI, Charles I, Charles II, James II as James VII, William III as William II, Mary II, Anne

In 1603, when Queen Elizabeth I of England, the last Tudor monarch died, James VI, King of Scots became King of England as King James I of England. This was a personal union, the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain separate. James VI, King of Scots was the only child of Mary, Queen of Scots and her second husband (and first cousin) Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, both grandchildren of James IV, King of Scots and Margaret Tudor who was the daughter of King Henry VII of England and the sister of King Henry VIII of England. In terms of primogeniture, James VI was the next in line to the English throne and on her deathbed, Queen Elizabeth I of England gave her assent that James should succeed her.

The English Stuart monarchs that followed James I were all sovereigns of the Kingdom of England and separately sovereigns of the Kingdom of Scotland. Some of them had two different regnal numbers reflecting the English sequence of sovereigns and the Scottish sequence of sovereigns – William III of England was the third William to reign in England but was the second William to reign in Scotland so he was William II, King of Scots. During the reign of Queen Anne, England and Scotland were formally united into Great Britain by the Acts of Union 1707. The sovereign then was King/Queen of Great Britain.

Prince of Orange, Count of Nassau, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Gelderland, and Overijssel

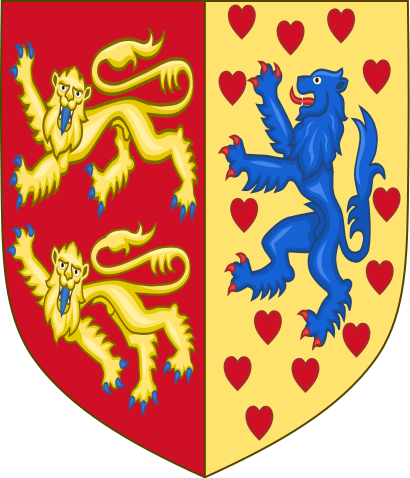

Coat of Arms of the Prince of Orange; Credit – Wikipedia

King William III of England, who came to the English throne as a joint ruler with his wife and first cousin Queen Mary II of England, was also Willem III, Sovereign Prince of Orange, Count of Nassau, and Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Gelderland, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic. William inherited the principality of Orange from his father, Willem II, Prince of Orange, who died a week before William’s birth. His mother Mary, Princess Royal was the daughter of King Charles I of England. William and Mary had no children and so William’s first cousin once removed, Johan Willem Friso, became Prince of Orange.

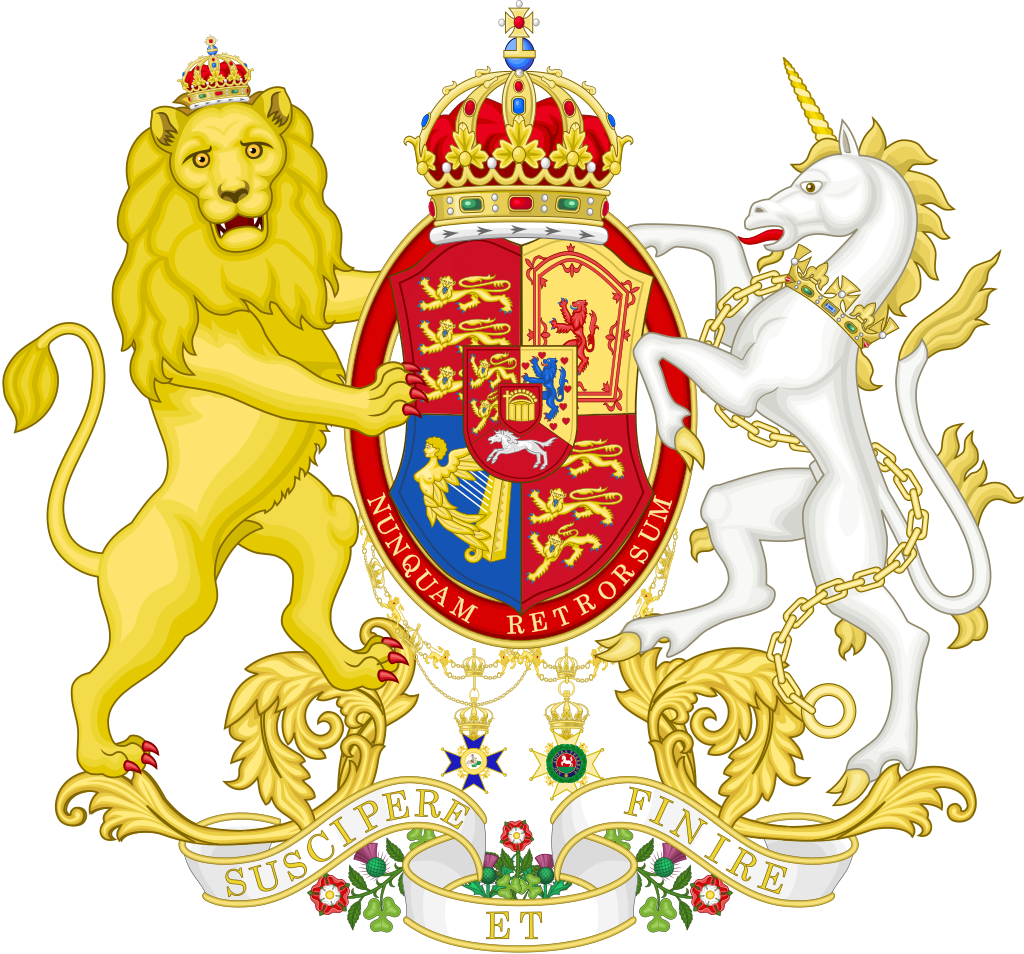

Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire, Duke of Brunswick-Luneburg

Coat of arms of Brunswick-Lüneburg; Credit – Wikipedia

- Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire, Duke of Brunswick-Luneburg: George I, George II, George III

The Duchy of Brunswick-Luneburg and the Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg, located in northwestern Germany, was an Electorate of the Holy Roman Empire. It was commonly known as the Electorate of Hanover after its capital city of Hanover.

The Prince-Electors of the Holy Roman Empire (Electors for short) elected the Holy Roman Emperor. The Holy Roman Empire was a limited monarchy composed kingdoms, principalities, duchies, counties, prince-bishoprics, and Free Imperial Cities in Central Europe from 800 – 1806.

When the Stuart dynasty appeared to be dying out, Parliament passed the Act of Settlement 1701, giving the succession to the British throne to Sophia of the Palatinate, Electress of Hanover and her non-Catholic heirs. This act ensured the Protestant succession and bypassed many Catholics who had a better hereditary claim to the throne. Sophia’s mother was Elizabeth Stuart who was the second child and eldest daughter of James VI, King of Scots / James I, King of England and Ireland. Sophia narrowly missed becoming queen, having died two months before the last Stuart monarch Queen Anne. Sophia’s son George, Elector of Hanover, became King George I of Great Britain. George remained Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire, Duke of Brunswick-Luneburg and his son George II and great-grandson George III inherited those titles.

King of Hanover, Duke of Brunswick-Luneburg

Coat of Arms of the Kingdom of Hanover; Credit – By Glasshouse – Own work, using elements by Sodacan, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=78034759

- King of Hanover, Duke of Brunswick-Luneburg: George III, George IV, William IV

The Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor Franz II (from 1804, Emperor Franz I of Austria) abdicated, following a military defeat by the French under Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz. After the final defeat of Napoleon in 1814, much of Europe was reorganized. The Hanover territories became the Kingdom of Hanover and became a personal union with the United Kingdom.

The personal union with the United Kingdom ended in 1837 upon the accession of Queen Victoria. The succession to the throne of Hanover followed Salic Law which did not allow female succession and so Victoria could not inherit the Hanover throne. Instead, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the eldest surviving son of King George III, became King of Hanover. His son George succeeded him as King George V of Hanover but he reigned for only fifteen years. He was exiled from Hanover in 1866 as a result of his support for Austria in the Austro-Prussian War and Hanover was annexed by Prussia.

Empress/Emperor of India

New Crowns for Old, the cartoon’s caption references a scene in Aladdin where lamps are exchanged. The Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, is offering Queen Victoria an imperial crown in exchange for an earl’s coronet. She made him the Earl of Beaconsfield at this time; Credit – Wikipedia

- Empress/Emperor of India: Victoria, Edward VII, George V, Edward VIII, George VI

One thing Queen Victoria wanted was an imperial title. She was disturbed because Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia held a higher rank than her and was appalled that her eldest daughter Victoria, Princess Royal who was married to the Crown Prince of Prussia and the future German Emperor, would outrank her when her husband came to the throne.

Queen Victoria pressured Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli to introduce a bill that would make her Empress of India. At the time, India was a colony of the United Kingdom. Disraeli did so but his handling of the bill was awkward. He did not notify either the Prince of Wales or the Liberal opposition. When they found out, the Prince of Wales was irritated and the Liberals went into motion with a full-scale attack. Disraeli was reluctant to bring the bill to a vote because he thought it would be defeated. However, it passed with a majority of 75.

On January 1, 1877, Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India. For the rest of her life, Victoria signed her name “Victoria R & I” – Regina et Imperatrix in Latin, Queen and Empress in English. Four of Victoria’s successors, her son Edward VII, her grandson George V and her great-grandsons Edward VIII and George VI also were Emperors of India. George VI ceased to use the title when India became an independent country in 1947.

Head of the Commonwealth

Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations; Credit – By Rob984 – Derived from File:BlankMap-World-Microstates.svg, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50344792

- Head of the Commonwealth: George VI, Elizabeth II

The Commonwealth of Nations, established in 1949, is an intergovernmental organization of fifty-three member nations that are mostly former territories of the United Kingdom. The British sovereign is head of state of sixteen member states, known as the Commonwealth realms, while thirty-two other members are republics and five others have different monarchs.

The Head of the Commonwealth is the “symbol of their free association” and serves as a leader, alongside the Commonwealth Secretary-General and Commonwealth Chair-in-Office. The position of Head of the Commonwealth is technically not hereditary and does not necessarily have to be the sovereign or a member of the royal family. However, following the 2018 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, Commonwealth leaders officially declared that Charles, Prince of Wales would be the next Head of the Commonwealth, and upon the death of his mother Queen Elizabeth II in 2022, King Charles III became the Head of the Commonwealth.

Sovereign of Other Realms

Currently, the British sovereign is also the sovereign of fourteen other countries, besides the United Kingdom: Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Jamaica, The Bahamas, Grenada, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Belize, Antigua and Barbuda and Saint Kitts and Nevis.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.