compiled and revised by Susan Flantzer

Front Page of The New York Times on November 11, 1918; Credit – Wikipedia

At 11 AM on November 11, 1918 – “the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month” – a ceasefire ending World War I went into effect. The Russian, German, Austrian, and Ottoman Empires had crumbled, the royal landscape of Europe had changed forever, numerous nations regained their former independence, new nations were created, and about 10 million military personnel and about 7 million civilians had died.

Armistice Day, November 11, is still commemorated in many countries. In the United States, it is Veterans Day, a day to honor the service of all American military veterans. In the United Kingdom and Commonwealth countries, it is Remembrance Day, honoring the memory of those who served in World War I and veterans of all subsequent wars involving British and Commonwealth troops.

All photos unless noted are from Wikipedia. For comparison, see Unofficial Royalty: European Monarchies at the Start of World War I in 1914

****************************

LOST THRONES DURING WORLD WAR I

Principality of Albania

Wilhelm of Wied, Sovereign Prince of Albania (reigned 1914)

Wikipedia: Prince Wilhelm of Wied, Prince of Albania

William of Wied, Sovereign Prince of Albania began his on March 7, 1914. A German prince, he had been chosen to rule in Albania by the Great European Powers but things soon got very bad for William. Albania was in a state of civil war by July 1914, Greece had occupied southern Albania, World War I had started, and when the Albanian government collapsed, William left the country on September 3, 1914. Despite leaving Albania, William insisted that he was still the head of state, however, a four-member regency actually ruled. William of Wied died in Predeal, Romania on April 18, 1945, at the age of 69.

Eventually, in 1925, Albania was declared a republic with Ahmet Zogu as President who then declared himself King Zog and reigned from 1928 – 1939, until Mussolini’s Italian forces invaded Albania. After 1939, Zog lived in exile in England, then Egypt, and finally France where he died on April 9, 1961, at the age of 65.

****************************

Austrian-Hungarian Empire

The Austrian-Hungarian Empire collapsed with dramatic speed during the autumn of 1918. The following countries were formed (entirely or in part) on the territory of the former Austrian-Hungary Empire:

- German Austria and the First Austrian Republic

- Hungarian Democratic Republic, Hungarian Soviet Republic, and the Kingdom of Hungary

- Czecho-Slovakia (“Czechoslovakia” from 1920 to 1938)

- State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs (joined December 1, 1918, with the Kingdom of Serbia to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia)

- The second Polish Republic

- West Ukrainian People’s Republic

- Duchy of Bukovina and Transylvania was joined to the Kingdom of Romania

- Austro-Hungarian lands were also ceded to the Kingdom of Romania and the Kingdom of Italy

Karl I, Emperor of Austria (reigned 1916 – 1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Karl I, Emperor of Austria

On November 11, 1918, the same day as the armistice ending World War I, Karl issued a proclamation in which he recognized the rights of the Austrian people to determine their form of government and released his government officials from their loyalty to him. On November 13, 1918, Karl issued a similar proclamation for Hungary. Karl did not use the term “abdicate” in his proclamations and would never admit that he abdicated. Karl and his family eventually settled on the Portuguese island of Madeira. In March of 1922, Karl caught a cold which developed into bronchitis and further developed into pneumonia. After suffering two heart attacks and respiratory failure, Karl died on April 1, 1922, at the age of 34.

***********************

German Empire

States of the German Empire (Prussia shown in blue); Credit – Wikipedia

The German Empire consisted of 27 constituent states, most of them ruled by royal families. The constituent states retained their own governments but had limited sovereignty. For example, both postage stamps and currency were issued for the German Empire as a whole. While the constituent states issued their own medals and decorations, and some had their own armies, the military forces of the smaller ones were put under Prussian control. In wartime, armies of all the constituent states would be controlled by the Prussian Army and the combined forces were known as the Imperial German Army. In November 1918, all sovereigns of constituent states of the German Empire were forced to abdicate.

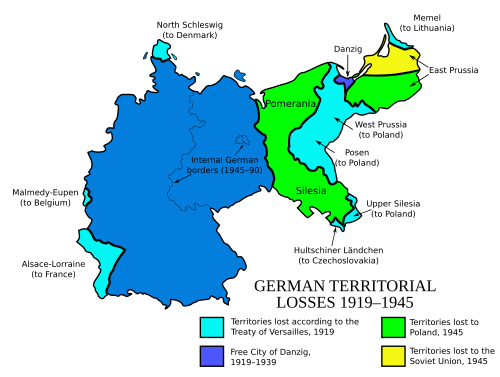

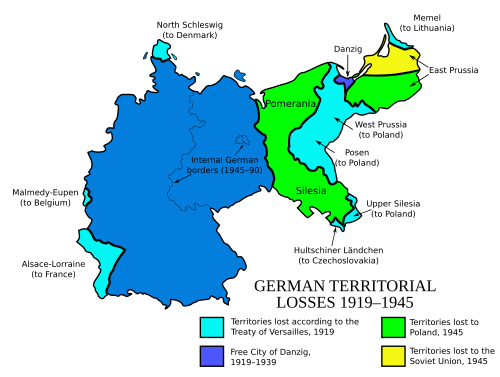

German territorial losses, 1919–1945; Credit – Wikipedia

After World War I, the remnants of the German Empire became the Weimar Republic, the unofficial, historical designation for the German state during the years 1919 to 1933. The Weimar Republic faced numerous problems including extreme inflation, political extremism, and poor relationships with the victors of World War I. In 1933, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor with the Nazi Party being part of a coalition government. Within a few months, constitutional government and civil liberties were gone. Hitler seized complete power and the founding of a single-party state began the Nazi era.

German Empire, Kingdom of Prussia: Wilhelm II, German Emperor, King of Prussia (reigned 1888–1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Wilhelm II, German Emperor

In the aftermath of World War I, Germany had a revolution that resulted in the replacement of the monarchy with a republic. Wilhelm abdicated on November 9, 1918. On November 10, 1918, Wilhelm Hohenzollern crossed the border by train and went into exile in the Netherlands, never to return to Germany. He first settled in Amerongen, living in the castle there. In 1919, Wilhelm purchased Huis Doorn, a small manor house outside of Doorn, a small town near Utrecht in the Netherlands, and moved there in 1920. He lived at Huis Doorn until his death in 1941 at the age of 82.

****************************

German Kingdoms

Bavaria – Ludwig III, King of Bavaria (reigned 1913–1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Ludwig III, King of Bavaria

As World War I was drawing to a close, the German Revolution broke out in Bavaria. Ludwig fled Munich with his family, taking up residence at Anif Palace near Salzburg, thinking it would just be a temporary move. A week later, on November 13, 1918, King Ludwig III would be the first monarch in the German Empire to be deposed, bringing an end to 738 years of rule by the Wittelsbach dynasty.

He returned to Bavaria, living at Wildenwart Castle, Fearing that his life was in danger, he soon left the country, traveling to Hungary, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland. He returned to Wildenwart Castle in April 1920 and remained until the following fall, when he traveled to his castle Nádasdy in Sárvár, Hungary where he lived until he died on October 18, 1921, at the age of 76.

Saxony – Friedrich Augustus III, King of Saxony (reigned 1904–1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Friedrich Augustus III, King of Saxony

By the end of World War I, unrest had reached most of the major cities in Saxony. Unlike many of his peers, Friedrich August refused to suppress the uprisings by military force. Instead, on November 13, 1918, he released the allegiance of his military, and formally abdicated the Saxon throne, bringing about the end of the monarchy. He retired to Sibyllenort Castle in Lower Silesia (now Poland) where he would live out the rest of his life. King Friedrich August III died on February 18, 1932, at the age of 66 at Sibyllenort Castle after suffering a stroke.

Württemberg – Wilhelm II, King of Württemberg (reigned 1891–1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Wilhelm II, King of Württemberg

King Wilhelm’s reign came to an end on November 30, 1918, after the fall of the German Empire led to the abdications of all of the ruling families. Before formally abdicating, Wilhelm negotiated with the new government to receive an annual income for himself and his wife, and also retained Schloss Bebenhausen, where the couple lived for the remainder of their lives. The last King of Württemberg died at Schloss Bebenhausen on October 2, 1921, at the age of 73.

****************************

German Grand Duchies

Baden – Friedrich II, Grand Duke of Baden (reigned 1907-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Friedrich II, Grand Duke of Baden

When Wilhelm II, German Emperor abdicated in 1918, riots broke out throughout the German Empire, and Friedrich and his family were forced to flee Karlsruhe Palace, for Zwingenberg Castle in the Neckar valley. They then arranged to stay at Langenstein Castle, where Friedrich formally abdicated the throne of Baden on November 22, 1918. Nearly blind and in poor health, Grand Duke Friedrich II died in Badenweiler on August 8, 1928, at the age of 71.

Hesse and by Rhine – Ernst Ludwig, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine (reigned 1892-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Ernst Ludwig, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine

Sadly, the later years of Ernst Ludwig’s life were marred by tragedy. World War I brought the murders of two sisters, Alix (Emperor Alexandra Feodorovna) and Ella (Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna), in Russia, as well as the loss of the Grand Ducal throne. With the fall of the German states, Ernst Ludwig refused to abdicate but still lost his throne on November 9, 1918. However, he was allowed to remain in Hesse and retained several of the family’s properties. Ernst Ludwig of Hesse died at Wolfsgarten Castle on October 9, 1937, at the age of 68. Tragically, just weeks later, a plane crash in Belgium took the lives of many of his remaining family – his widow, elder son, daughter-in-law, and two grandsons – who were on the way to a family wedding in England.

Mecklenburg-Schwerin – Friedrich Franz IV, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (reigned 1897-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Friedrich Franz IV, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

On November 14, 1918, Friedrich Franz IV was forced to abdicate. and forced into exile. Friedrich Franz and his family traveled to Denmark at the invitation of his sister Queen Alexandrine. There, they lived at Sorgenfri Palace for a year, before being permitted to return to Mecklenburg and recovering several of the family’s properties.

After World War II, Friedrich Franz’s former states became part of Communist East Germany. Along with his wife and son Christian Ludwig, Friedrich Franz fled to Glücksburg Castle in West Germany, the home of his youngest daughter and her husband, with the intention of returning to Denmark. However, Friedrich Franz became ill, he died there on November 17, 1945, at the age of 63.

Mecklenburg-Strelitz – Adolf Friedrich VI, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (reigned 1914-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Adolf Friedrich VI, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

A woman with whom Adolf Friedrich had a relationship claimed to have correspondence that linked him to “certain homosexual circles” and threatened to release them to the public unless he gave in to her demands for more money. With World War I still raging, and the possibility of these letters being made public, the 35-year-old Grand Duke Adolf Friedrich VI left his home on the evening of February 23, 1918, to take his dog for a walk. The following morning, his body was found in a nearby canal with a gunshot wound to his head. He left behind a suicide note which suggested that a woman was attempting to smear his name.

In his will, he had requested that Duke Christian Ludwig of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, the son of his good friend Grand Duke Friedrich Franz IV of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, become the new Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. The heir presumptive – Duke Carl Michael – lived in Russia and had previously indicated that he wished to renounce his rights to the grand ducal throne. However, before the matter could be resolved, Germany became a republic and the various sovereigns lost their thrones.

Oldenburg – Friedrich Augustus II, Grand Duke of Oldenburg (reigned 1900-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Friedrich Augustus II, Grand Duke of Oldenburg

With the fall of the German Empire at the end of World War I, Friedrich August was forced to abdicate his throne on November 11, 1918. He retired to Schloss Rastede where he took up farming. Claiming an “extremely precarious” financial situation, he petitioned the Oldenburg government for an annual allowance the year after his abdication. Friedrich August II, the last Grand Duke of Oldenburg, died at Schloss Rastede on February 24, 1931, at the age of 78.

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach – Wilhelm Ernst, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (reigned 1901-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Wilhelm Ernst, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

Wilhelm Ernst was forced to abdicate on November 9, 1918. He was stripped of his throne and his properties and forced into exile. With his family, he took up residence at Schloss Heinrichau, the family’s estate in Heinrichau, Silesia (now Henryków, Poland). He died there less than five years later, on April 24, 1923, at the age of 46.

****************************

German Duchies

Anhalt – Joachim Ernst, Duke of Anhalt

Unofficial Royalty: Joachim Ernst, Duke of Anhalt

The year 1918 saw three Dukes of Anhalt. Friedrich II died in April and was succeeded by his brother Eduard Georg Wilhelm who then died in September 1918. He was succeeded by his eldest surviving son 17-year-old Prince Joachim Ernst under the regency of Eduard’s younger brother, Prince Aribert. Joachim Ernst’s brief reign came to an end on 12 November 12, 1918, when the regent Prince Aribert abdicated in his name. After 1918, Schloss Ballenstedt am Harz remained as the residence of the Anhalt family. Joachim Ernst married twice and had five children.

During World War II, Joachim Ernst was arrested in January 1944 and sent to the Dachau concentration camp. At the end of World War II, Joachim Ernst was arrested by the Soviet occupation troops and sent to the former Buchenwald concentration camp, then a Soviet prison camp called NKVD special camp Nr. 2. He became seriously ill and died on February 18, 1947, at the age of 46.

Brunswick – Ernst Augustus III, Duke of Brunswick (reigned 1913-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Ernst Augustus III, Duke of Brunswick

On November 8, 1918, Ernst Augustus was forced to abdicate his throne. For the next thirty years, he would remain head of the House of Hanover, living in retirement on his various estates. He lived long enough to see one of his children become a consort to a monarch. In 1947, his daughter Frederica became Queen of Greece when her husband Prince Paul of Greece succeeded his brother as King. Ernst Augustus is the maternal grandfather of Queen Sofia of Spain and the former King Constantine II of Greece. He died at Marienburg Castle in 1953 at the age of 65.

Saxe-Altenburg – Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg (reigned 1908-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg

Ernst was one of the first sovereigns to realize major changes were coming for Germany and he quickly arrived at an amicable settlement with his subjects. He was forced to abdicate as Duke of Saxe-Altenburg on November 13, 1918. After his abdication, Ernst retired to a hotel in Berlin. After World War II, Ernst became the only former reigning German prince who accepted German Democratic Republic (East Germany) citizenship, refusing to leave his home and relocate to the British occupation zone. He died on March 22, 1955, at the age of 83, the last survivor of the German sovereigns who had reigned until 1918.

Saxe-Coburg and Gotha – Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (reigned 1900-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

On November 9, 1918, the Workers’ and Soldiers Council of Gotha, deposed Charles Edward, a grandson of Queen Victoria, as Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Five days later, he signed a declaration relinquishing his rights to the throne. During the 1920s, Charles Edward joined the Nazi Party and became a prominent member. After the end of World War II, Charles Edward was placed under house arrest at his residence because of his Nazi sympathies. In 1949, a denazification appeals court classified Charles Edward as a Nazi Follower, Category IV. He was heavily fined and almost bankrupted. Charles Edward spent the last years of his life in seclusion. He died on March 6, 1954, at the age of 69 in Coburg.

Saxe-Meiningen – Bernhard III, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen (reigned 1914-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Bernhard III, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen

On November 10, 1918, Bernhard abdicated due to pressure from the Meininger Workers and Soldiers Council. His half-brother Ernst waived his succession rights on November 12, 1918, officially ending the monarchy of the Duchy of Saxe-Meiningen. Bernhard lived his remaining years at Schloss Altenstein in Bad Liebenstein, Germany where he died on January 16, 1928, at the age of 76.

****************************

German Principalities

Lippe – Leopold IV, Prince of Lippe (reigned 1905 – 1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Leopold IV, Prince of Lippe

Because of the November Revolution after World War I, Leopold was forced to abdicate on November 12, 1918. However, Leopold negotiated a treaty with the new government that allowed his family to remain in Lippe. Leopold died in Detmold, the former capital of the Principality of Lippe on December 30, 1949, at the age of 78.

Reuss-Greiz – Heinrich XXIV, 6th Prince Reuss of Greiz Older Line (reigned 1902-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Heinrich XXIV, Prince Reuss of Greiz

Because of his physical and mental disabilities as a result of an accident in his childhood, Heinrich XXIV was unable to govern and the Principality of Reuss-Greiz was ruled by a regent. On November 11, 1918, the regent, Heinrich XXVII, 5th Prince Reuss of Gera, abdicated in the name of Heinrich XXIV. After the abdication, Heinrich XXIV retained the right of residence of the Lower Castle in Greiz and lived there until his death in 1927 at the age of 49.

Reuss-Gera – Heinrich XXVII, 5th Prince Reuss Younger Line (reigned 1913-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Heinrich XXVII, Prince Reuss Younger Line

Besides being Sovereign Prince Reuss, Younger Line, Heinrich XXVII was Regent of the Principality of Reuss of Greiz, Older Line from 1908 – 1918. (See above.) On November 11, 1918, Heinrich XXVII abdicated his position as Sovereign Prince Reuss, Younger Line and as Regent abdicated for the disabled Heinrich XXIV, 6th Prince Reuss of Greiz, Older Line. The new government made an agreement with Heinrich XXVII and granted him some castles and land. Heinrich XXVII died on November 21, 1928, at the age of 70.

Schaumburg-Lippe – Adolf II, Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe (reigned 1911-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Adolf II, Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe

Adolf II was forced to abdicate on November 15, 1918, and was exiled to Brioni, then Italy, now in Croatia. 53-year-old Adolf and his wife actress Ellen von Bischoff-Korthaus, who he married in 1920, were killed in a plane crash in Zumpango, Mexico on March 26, 1936.

Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt and Schwarzburg-Sondershausen – Günther Victor, Prince of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt and Schwarzburg-Sondershausen (reigned 1909-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Günther Victor, Prince of Schwarzburg

Günther Victor, the last German prince to renounce his throne, abdicated on November 22, 1918. He made an agreement with the government that awarded him an annual pension and the right to use several of the family residences. Günther Victor died on April 21, 1925, at the age of 72.

Waldeck-Pyrmont – Friedrich, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont (reigned 1893-1918)

Unofficial Royalty: Friedrich, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont

Friedrich was the brother of Marie, the first wife of King Wilhelm II of Württemberg (who also had to abdicate), Emma who married King Willem III of the Netherlands, and Helena, the wife of Queen Victoria’s hemophiliac son Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany and the mother of Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (who also had to abdicate). Friedrich abdicated on November 13, 1918, and negotiated an agreement with the government that gave him and his descendants the ownership of the family home Arolsen Castle and Arolsen Forest. He died on May 26, 1946, aged 81, in Arolsen, the former capital of the Principality of Waldeck-Pyrmont.

***********************

Kingdom of Montenegro

Nikola I, King of Montenegro (reigned 1860–1918)

Wikipedia: Nikola I, King of Montenegro

After the end of World War I, a Serb-dominated meeting decided to depose Nikola and annex Montenegro to Serbia. On November 26, 1918, Serbia (including Montenegro) merged with the former South Slav territories of Austria-Hungary to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, which was renamed Yugoslavia in 1929. Nikola went into exile in France in 1918 but continued to claim the throne until his death on March 1, 1921, at the age of 79.

***********************

Russian Empire

Russia entered World War I with great patriotism and enthusiasm but the effects of the war caused food and fuel shortage, rising inflation, strikes among low-paid factory workers, and restlessness among the peasants who wanted reforms of land ownership. The tsarist regime was overthrown during the 1917 February Revolution. The government that was formed after the February Revolution was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in the 1917 October Revolution. This ultimately resulted in the Communist Soviet Union which fell in 1991.

Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (reigned 1894–1917)

Unofficial Royalty: Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia

On March 15, 1917, Nicholas II was forced from the throne. He formally abdicated for himself and his son, making his younger brother, Michael, the new Emperor. Michael, however, refused to accept until the Russian people could decide on continuing the monarchy or establishing a republic, which never happened. From March 1917 until July 1918, Nicholas II and his family were held in protective custody, first at Alexander Palace outside of St. Petersburg and then at the Governor’s Mansion in Tobolsk, Siberia, and lastly at the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg, Siberia. On July 17, 1918, Nicholas II, his wife, their five children, their doctor, and three servants were shot to death in the basement of the Ipatiev House.

***************************

KEPT THEIR THRONES BUT NOT FOR LONG

Some European monarchies survived World War I but ceased to exist sometime during the 20th century.

Former Tsar Simeon II in 2005

Kingdom of Bulgaria: Due to feeling responsible for being on the losing side of World War I, Tsar Ferdinand I, born Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, abdicated in favor of his son Boris on October 3, 1918. Ferdinand returned to Coburg, his birthplace, and there on September 10, 1948, at the age of 87.

After the outbreak of World War II, Tsar Boris III was courted by Hitler to join his alliance. Boris agreed to several things including the Law for Protection of the Nation, which imposed restrictions on Jewish Bulgarians. However, during a meeting with Hitler in 1943, Boris refused to deport Bulgarian Jews and declare war on Russia. Just weeks later, on August 28, 1943, Tsar Boris III died in Sofia. The circumstances of his death remain mysterious, with many believing that Boris had been poisoned because of his refusal to concede to the demands of the Nazis.

Boris was succeeded by his 6-year-old son Tsar Simeon II. A Council of Regency was established but the following year the Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria, and the regents were deposed and replaced. The Bulgarian monarchy was overthrown in 1946, replaced with a Communist government, and the royal family was forced to leave the country. Following the fall of the communist regime in 1989, Simeon was finally able to return to his homeland. He was known as Simeon Borisov Sakskoburggotski, the Bulgarian version of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. In 2001, he was elected Prime Minister of Bulgaria and served until 2005. He remained head of his political party until stepping down in 2009.

****************************

Former King Constantine II and his wife, born Princess Anne-Marie of Denmark, in 2010

Kingdom of Greece: After a series of political problems in the 1920s and 1930s, the Greek monarchy was abolished in 1924 when a republic was declared. In 1935, the monarchy was restored. In 1964, 23-year-old King Constantine II succeeded his father. On April 21, 1967, a coup d’état led by a group of army colonels took over Greece, and the royal family was forced to flee, living first in Italy and then in England. A republic was declared in 1975 following a referendum that chose to not restore the monarchy. The Greek government did not permit King Constantine II to return to Greece until 1981 when he was allowed to attend the funeral of his mother. After 2003, when the property dispute between King Constantine and the government of Greece was more settled, he was able to make visits to Greece and own property there.

****************************

Umberto in 1944

Kingdom of Italy: Umberto II, the last King of Italy, took the throne in 1946 after the abdication of his father King Vittorio Emanuele III. Two months later, a referendum was held and the majority voted for Italy to become a Republic. On June 12, 1946, King Umberto II was formally deposed and left Italy, banned from ever setting foot on Italian soil. 78-year-old Umberto died on March 18, 1983, in a hospital in Geneva, Switzerland.

****************************

Mehmed in 1918

Ottoman Empire: World War I was a disaster for the Ottoman Empire. Allied forces had conquered Baghdad, Damascus, and Jerusalem during the war and most of the Ottoman Empire was then divided among the European allies. The Sultanate limped along for four more years. The Grand National Assembly of Turkey abolished the Sultanate on November 1, 1922, and the last Sultan, Mehmed VI was expelled from the country. The former Sultan went into exile in Malta and later lived on the Italian Riviera, dying on 16 May 16, 1926, in Sanremo, Italy at the age of 65.

****************************

Former King Mihai in 2007

Kingdom of Romania: King Mihai (Michael) was the last King of Romania. Because his father renounced his succession rights, five-year-old Mihai succeeded his grandfather in 1927. In June 1930, in a coup d’état, Mihai’s father King Carol II came to the throne until 1940, when another coup d’état took place. Carol was forced to formally abdicate and Mihai was once again King of Romania. Two years after World War II ended, Romania had a Communist government, and Mihai was forced to sign a document of abdication and leave the country. Mihai and his family first lived in Italy and then in Switzerland. In 1997, after the fall of the Communist government, the Romanian government restored Mihai’s citizenship and in the following years, several properties were returned to the royal family and Mihai and his family lived part of the time in Romania. Mihai died at his residence in Switzerland on December 5, 2017, at the age of 96.

****************************

Former King Peter II in 1966

Kingdom of Serbia/Kingdom of Yugoslavia: King Peter II was the last King of Yugoslavia. He spent World War II in exile in England. In November 1945, the new Communist government in Yugoslavia abolished the monarchy and formally deposed King Peter II. Peter left England and lived in France and Switzerland before settling in the United States in 1949. Suffering from cirrhosis of the liver, Peter died on November 3, 1970, in Denver, Colorado, following a failed liver transplant. Per his wishes, he was interred at the Saint Sava Monastery Church in Libertyville, Illinois. To date, he is the only European monarch to be buried in the United States. In January 2013, his remains were returned to Serbia and buried in the Royal Family Mausoleum beneath St. George’s Church at Oplenac.

****************************

Alfonso in 1930

Kingdom of Spain: King Alfonso XIII of Spain was the Spanish sovereign from his birth since his father died while his mother was pregnant. In 1923, General Miguel Primo de Rivera seized power in a military coup, with the support of King Alfonso XIII and served as dictator for the next seven years. In January 1930, due to economic problems and general unpopularity, Primo de Rivera resigned as Prime Minister. Alfonso had been so closely associated with the Primo de Rivera dictatorship that it was difficult for him to distance himself from the regime he had supported for almost 7 years. In 1931, elections were held, resulting in the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic. Alfonso and his family fled Spain, settling in France and then Italy. On February 28, 1941, King Alfonso XIII died at the Grand Hotel in Rome at the age of 54.

In 1969, Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, who ruled Spain from 1936 until his death in 1975, named King Alfonso XIII’s grandson Juan Carlos as his successor, giving him the newly created title “The Prince of Spain”. Franco died on November 22, 1975, and Juan Carlos was proclaimed King. In 2014, King Juan Carlos I abdicated in favor of his son King Felipe VI.

***************************