by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2017

Robert III Curthose, Duke of Normandy; Credit – Wikipedia

Robert Curthose, the eldest son of King William I of England (the Conqueror) and Matilda of Flanders, was born in Normandy around 1051. Despite being the eldest son, Robert did not follow his father upon the English throne. Robert’s nickname Curthose comes from the Norman French courtheuse, meaning “short stockings.” The chroniclers William of Malmesbury and Orderic Vitalis reported that the insulting name came from Robert’s father who was making fun of his son’s short stature.

Robert had at least nine siblings. The birth order of the boys is clear, but that of the girls is not. The list below is not in birth order. It lists Robert’s brothers first in their birth order and then his sisters in their probable birth order.

- Richard of Normandy (circa 1054 – circa 1070), died in a hunting accident in the New Forest

- William II Rufus, King of England (1056-1060 – 1100), unmarried, killed in the New Forest

- Henry I, King of England (1068 – 1135), married (1) Edith of Scotland, had one son and one daughter (2) Adeliza of Louvain, no children

- Agatha of Normandy died before 1074, unmarried

- Adeliza of Normandy (circa 1055 – before 1113), probably a nun at the Abbey of St Léger in Préaux, Duchy of Normandy

- Cecilia of Normandy (circa 1056 – 1127), Abbess of Holy Trinity in Caen

- Matilda of Normandy (circa 1061 – c. 1086)

- Constance of Normandy (1057-1061 – 1090, married Alan IV, Duke of Brittany, no issue

- Adela of Normandy (circa 1067 – 1137), married Stephen II, Count of Blois, had ten children including King Stephen of England

As a child, Robert was engaged to marry Marguerite of Maine, daughter of Hugh IV, Count of Maine, but Marguerite died in 1063 before their marriage could take place. Robert was brave and well-trained as a knight but also had a lazy and weak character.

In 1066, Robert’s father, William III, Duke of Normandy, invaded England and defeated the last Anglo-Saxon King, Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings. The Duke of Normandy was now also King William I of England. Even before the division of land occurred in 1087, Robert and his brothers had a strained relationship. The contemporary chronicler Orderic Vitalis, wrote about an incident at L’Aigle in Normandy in 1077. William Rufus and Henry grew bored playing dice and decided to make mischief by emptying a chamber pot on their brother Robert from an upper gallery. Robert was infuriated, a brawl broke out and their father had to intercede to restore order. Angered because his father did not punish his brothers, Robert and his followers attempted to siege the castle at Rouen (Normandy) but were forced to flee when the Duke of Normandy attacked their camp. This led to a three-year estrangement between Robert and his family which only ended through the efforts of Robert’s mother.

In 1087, King William I divided his lands between his two eldest surviving sons. Robert Curthose was to receive the Duchy of Normandy and William Rufus was to receive the Kingdom of England. Henry was to receive 5,000 pounds of silver and his mother’s English estates. King William I of England (the Conqueror) died on September 9, 1087. Robert Curthose became Robert III Curthose, Duke of Normandy and William Rufus became King William II Rufus of England. Henry received the money, but no land.

William Rufus and Robert Curthose continued having a strained relationship. William Rufus alternated between supporting Robert against the King of France and opposing him for the control of Normandy. Henry was constantly being forced to choose between his two brothers and whichever brother he picked, he was likely to annoy the other. After William I died and his lands were divided, nobles who had land in both Normandy and England found it impossible to serve two lords. If they supported William Rufus, Robert might deprive them of their Norman land. If they supported Robert, they were in danger of losing their English land.

The only solution the nobles saw was to unite Normandy and England, and this led them to revolt against William Rufus in favor of Robert in the Rebellion of 1088, under the leadership of the Bishop Odo of Bayeux, the half-brother of William the Conqueror. The rebellion was unsuccessful partly because Robert never showed up to support the English rebels.

In 1096, Robert left for the Holy Land on the First Crusade. He mortgaged the Duchy of Normandy to his brother King William II Rufus to raise money for the crusade. The two older brothers made a pact stating that if one of them died without heirs, both Normandy and England would be reunited under the surviving brother. William Rufus then ruled Normandy as regent in Robert’s absence.

On August 2, 1100, King William II Rufus rode out from Winchester Castle on a hunting expedition to the New Forest, accompanied by his brother Henry and several nobles. According to most contemporary accounts, William Rufus was chasing after a stag followed by Walter Tirel, a noble. William Rufus shot an arrow but missed the stag. He then called out to Walter to shoot, which he did, but the arrow hit the king in his chest, puncturing his lungs, and killing him. Walter Tirel jumped on his horse and fled to France.

William Rufus’ elder brother, Robert Curthose, was still on Crusade, so the youngest brother Henry seized the crown of England for himself. Henry hurried to Winchester to secure the royal treasury. The day after William Rufus’ funeral at Winchester, the nobles elected Henry king. Henry then left for London where he was crowned three days after William’s death by the Bishop of London. King Henry I would not wait for the Archbishop of Canterbury to arrive. There is still speculation that there was a conspiracy to assassinate William Rufus.

On his way back from the Crusades, Robert married a wealthy heiress Sybilla of Conversano in 1100 at the bride’s hometown of Apulia (now in Italy). Unbeknownst to Robert, the death of his brother William Rufus removed the necessity of redeeming the Duchy of Normandy. Upon returning to Normandy, finding out that one brother was dead and the other brother had seized the English throne, Robert claimed the English crown based upon the pact he had made with William Rufus: that if one of them died without heirs, both Normandy and England would be reunited under the surviving brother. In 1101, Robert led an invasion to oust his brother Henry from the English throne. He landed at Portsmouth with his army but found there was little support for his cause. Robert was forced to renounce his claim to the English throne in the 1100 Treaty of Alton.

Robert and Sybilla had one son:

- William Clito (1102 – 1128), heir to the Duchy of Normandy, married (1) Sibylla of Anjou, no issue, marriage annulled (2) Joanna of Montferrat, no issue

Less than six months after her son’s birth, Sybilla died on March 18, 1103, at Rouen in Normandy and was buried at Rouen Cathedral. According to chroniclers Orderic Vitalis and Robert de Torigni, Sybilla was poisoned by her husband’s mistress Agnes de Ribemont.

In 1105, King Henry I invaded Normandy and defeated Robert’s army at the Battle of Tinchebray on September 28, 1106. Normandy remained a possession of the English crown for over a century. Robert was captured after the battle and spent the rest of his life imprisoned, first at

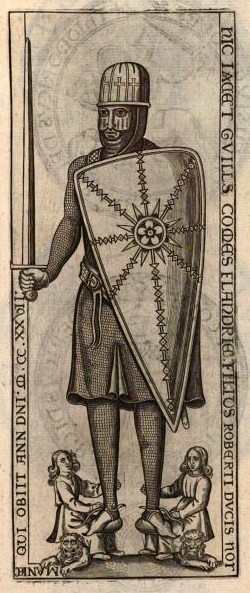

Devizes Castle for twenty years and then at Cardiff Castle for the remainder of his life. Robert Curthose lived into his eighties and died at Cardiff Castle on February 10, 1134. He was buried in the abbey church of St. Peter in Gloucester which later became Gloucester Cathedral. The memorial to him which can still be seen at Gloucester Cathedral is from a much later date.

Memorial to Robert Curthose at Gloucester Cathedral; Credit – By Nilfanion – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24852186

Robert’s only child, William Clito, was unlucky all his life. His attempts to invade Normandy failed twice (1119 and 1125). His first marriage to Sibylla of Anjou was annulled by the scheming of his uncle King Henry I. His second marriage to Joanna of Montferrat, half-sister of King Louis VI of France was childless. Louis VI did help William Clito become the Count of Flanders, but William Clito was wounded in a battle and died from gangrene at the age of 25 on July 28, 1128. He was buried at the Abbey of St. Bertin, a Benedictine abbey in Saint-Omer, France. He left no children and his imprisoned father survived him by six years.

William Clito; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Anglorum, Gesta Regum. “Robert II de Normandie.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 1063. Web. 31 Jan. 2017.

- “Robert Curthose.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 24 Jan. 2017. Web. 31 Jan. 2017.

“Roberto II di Normandia.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 31 Jan. 2017. - Susan Flantzer. “King Henry I of England.” British Royals. Unofficial Royalty, 30 Aug. 2015. Web. 31 Jan. 2017.

- Susan Flantzer. “King William I of England (the conqueror).” British Royals. Unofficial Royalty, 25 Aug. 2016. Web. 31 Jan. 2017.

- Susan Flantzer. (2016). King William II Rufus of England. [online] Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-william-ii-rufus-of-england/ [Accessed 20 Oct. 2019].

- “Sybilla of Conversano.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 29 Oct. 2016. Web. 31 Jan. 2017.

- “William Clito.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Oct. 2016. Web. 31 Jan. 2017.

- Williamson, David. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell, 1996. Print.