by Scott Mehl © Unofficial Royalty 2016

King George I of the Hellenes – source: Wikipedia

King George I of the Hellenes was born Prince Christian Vilhelm Ferdinand Adolf Georg of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, on December 24, 1845, at the Yellow Palace in Copenhagen. Known as Vilhelm, he was the son of Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg (later King Christian IX) and Princess Luise of Hesse-Kassel. He had five siblings:

- King Frederik VIII of Denmark (1843 – 1912), married Princess Louise of Sweden, had issue

- Princess Alexandra of Denmark (1844 – 1925), married King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, had issue

- Princess Dagmar of Denmark, Maria Feodorovna after marriage (1847 – 1928), married Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia, had issue

- Princess Thyra of Denmark (1853 – 1933), married Crown Prince Ernest Augustus of Hanover, 3rd Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale, had issue

- Prince Valdemar of Denmark (1858 – 1939), married Princess Marie of Orléans

In 1852, Vilhelm’s father was designated as heir-presumptive to the childless King Frederik VII of Denmark. Vilhelm’s title changed to Prince of Denmark. The family split their time between the Yellow Palace and Bernstorff Palace, which had been available to them following his father’s appointment. After his initial education at home, Vilhelm joined the Royal Danish Navy, attending the Royal Danish Naval Academy alongside his elder brother, Frederik.

Prince Vilhelm with his family, 1862. front: Princess Dagmar, Prince Valdemar, Queen Louise, Princess Thyra, Princess Alexandra; back: Prince Frederik, King Christian IX, Prince Vilhelm. source: Wikipedia

In 1862, King Otto of Greece (born Prince Otto of Bavaria) was deposed. Still wanting a monarchy, but rejecting Otto’s proposed successor, Greece began searching for a new King. Initially, the focus fell on Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh (the second son of Queen Victoria), who received overwhelming support from the Greek people. However, the London Conference of 1832 stipulated that no one from the ruling families of the Great Powers could accept the Greek throne. While several other European princes were suggested as possible sovereigns, the Greek people and the Great Powers soon chose Prince Vilhelm as their next King. On March 30, 1863, the 17-year-old Vilhelm was unanimously elected by the Greek National Assembly and took the name King George I of the Hellenes. A ceremonial enthronement was held in Copenhagen on June 6, 1863.

George made visits to Russia, England, and France, before arriving in Athens on October 30, 1863. From the beginning, George was determined to be very different than his predecessor. He quickly learned Greek and was often seen informally strolling through the streets of Athens. George had been accompanied to Greece by several advisors from Denmark. He soon sent them back to Denmark so it would not appear that he was influenced by his home country. George toured Denmarkthe following year and then demanded that the Assembly finally adopt a new constitution. Finally done, he took an oath on November 28, 1864, to defend the new constitution, establishing a constitutional monarchy in which the King deferred authority to the elected government. George quickly became very popular with the Greek people.

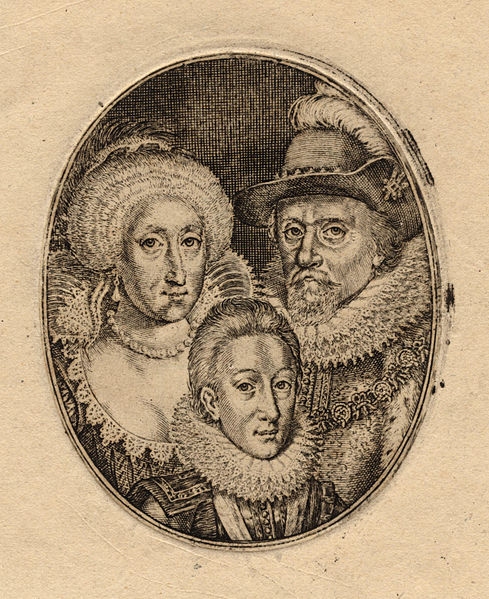

Olga and George – source: Wikipedia

In 1863, while visiting St. Petersburg before his arrival in Greece, King George first met his future wife Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna of Russia. She was the daughter of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich (a son of Nicholas I, Emperor of All Russia) and Princess Alexandra of Saxe-Altenburg. Four years later, while visiting his sister Dagmar, the wife of the future Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia, George met Olga again. By this time, George was looking for a wife, and marriage to a Russian Grand Duchess would be advantageous both politically and as far as the religion of future generations. While George remained Lutheran after taking the throne, future Greek sovereigns would be raised in the Greek Orthodox faith. Olga was smitten with George, and the two quickly fell in love. They married in Grand Church of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia on October 27, 1867, and went on to have eight children:

- King Constantine I (1868-1923) – married Princess Sophie of Prussia, had issue

- Prince George (1869-1957) – married Princess Marie Bonaparte, had issue

- Princess Alexandra (1870-1891) – married Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia, had issue

- Prince Nicholas (1872-1938) – married Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia, had issue

- Princess Maria (1876-1940) – married (1) Grand Duke George Mikhailovich of Russia, had issue; (2) Admiral Perikles Ioannidis, no issue

- Princess Olga (born and died 1880) – died in infancy

- Prince Andrew (1882-1944) – married Princess Alice of Battenberg, had issue

- Prince Christopher (18881940) – married (1) Nancy Leeds, no issue; (2) Princess Françoise of Orléans, had issue

King George and Queen Olga with six of their children, c1890. source: Wikipedia

George and his family spent much of their time at Tatoi, a 10,000-acre estate outside Athens which he had purchased in the 1870s. Along with the main palace, King George established a winery and a Danish-styled dairy farm. He established the Royal Cemetery on the grounds, following the death of his daughter, Princess Olga, in 1880. King George also acquired Mon Repos, a villa on the isle of Corfu, in 1864, which the royal family used as a summer residence. Mon Repos is probably best known today as the birthplace of George’s grandson, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, who was born there in 1921.

King George’s early reign saw constant upheaval, with 21 different governments in 10 years. Attempts to return the isle of Crete to Greek control were unsuccessful, which caused great tension among the Greek people. Following the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 (in which Greece remained neutral despite the attempts of George’s sister, Tsarevna Maria Feodorovna of Russia, to get Greece to join with the Russians), Greece claimed Crete and the regions of Epirus and Thessaly which were all under the Ottoman rule. Eventually, in 1881, the Ottomans ceded Thessaly.

The political climate in Crete remained tense, with the predominantly Greek population revolting against Turkish rule in 1897. The Great Powers stepped in, ordering both Greek and Turkish forces to withdraw, with Crete being under international control. While the Turks agreed, the Greek Prime Minister refused and sent troops to take the island. When forces crossed the Macedonian border, war broke out. By the end of April, the war was over, with Greece losing swiftly and severely. Following the defeat, King George lost much of his popularity and support from the Greek people, even considering abdication. But the following year, in February 1898, an assassination attempt was made on the King and his daughter Maria, while riding in an open carriage. Fortunately, both were unharmed, and he received an upswell of support from his subjects.

In the First Balkan War of 1912, Greece joined forces with Montenegro, Serbia, and Bulgaria in fighting against Turkey. This time, the Greek forces were victorious, and on November 12, 1912, led by Crown Prince Constantine, they took the city of Thessaloniki in what was then Macedonia. Three days later, King George arrived and rode through the streets accompanied by his son and the Prime Minister.

Grave of King George I of Greece, photo by Kostisl, source: Wikipedia

With his Golden Jubilee approaching, King George planned to abdicate following the celebrations planned for October 1913. However, his life would end several months before he had the chance. On March 18, 1913, while walking in Thessaloniki, Greece, King George was killed when an assassin shot him at close range in the back. The King died instantly. His body was returned to Athens, where it lay in state for three days in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens. Draped in both the Greek and Danish flags, his coffin was then interred in Royal Cemetery at Tatoi.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Greece Resources at Unofficial Royalty