Let the Hobbits and Wizards know that His Majesty King Charles III of the United Kingdom of Great Britian and Northern Ireland will return to public duties next Tuesday.

BBC: King Charles to resume public duties after progress in cancer treatment

Let the Hobbits and Wizards know that His Majesty King Charles III of the United Kingdom of Great Britian and Northern Ireland will return to public duties next Tuesday.

BBC: King Charles to resume public duties after progress in cancer treatment

by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

The Hawaiian Islands, located in the Pacific Ocean, were originally divided into several independent chiefdoms. The Kingdom of Hawaii was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great of the independent island of Hawaii, conquered the independent islands of Oahu, Maui, Molokai, and Lanai, and unified them under one government and ruled as Kamehameha I, King of the Hawaiian Islands. In 1810, the whole Hawaiian archipelago became unified when Kauai and Niihau voluntarily joined the Kingdom of Hawaii. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom: the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

In 1778, British explorer James Cook visited the islands. This led to increased trade and the introduction of new technologies and ideas. In the mid-19th century, American influence in Hawaii dramatically increased when American merchants, missionaries, and settlers arrived on the islands. Protestant missionaries converted most of the native people to Christianity. Merchants set up sugar plantations and the United States Navy established a base at Pearl Harbor. The newcomers brought diseases that were new to the indigenous people including influenza, measles, smallpox, syphilis, tuberculosis, and whooping cough. At the time of James Cook’s arrival in 1778, the indigenous Hawaiian population is estimated to have been between 250,000 and 800,000. By 1890, the indigenous Hawaiian population declined to less than 40,000.

In 1893, a group of local businessmen and politicians composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national overthrew Queen Liliuokalani, her cabinet, and her marshal, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii. This led to the 1898 annexation of Hawaii as a United States territory. On August 21, 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state of the United States.

In 1993, one hundred years after the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown, the United States Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Apology Resolution which “acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and further acknowledges that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaii or through a plebiscite or referendum”. As a result, the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom in Hawaii, was established along with ongoing efforts to redress the indigenous Hawaiian population.

********************

Liliuokalani, Queen of the Hawaiian Islands, 1891; Credit – Wikipedia

Liliuokalani, Queen of the Hawaiian Islands was the only queen regnant and the last monarch of the Hawaiian Islands, reigning from 1891 until she was deposed in 1893. She was the composer of Aloha ʻOe or Farewell to Thee, one of the most recognizable Hawaiian songs. Born Lydia Liliʻu Loloku Walania Kamakaʻeha on September 2, 1838, in Honolulu on the island of Oʻahu in the Kingdom of Hawaii, now in the state of Hawaii, she was the third but second surviving of the seven children and the eldest of the three daughters of first cousins Caesar Kaluaiku Kamakaʻehukai Kahana Keola Kapaʻakea and Analea Keohokālole. Liliuokalani was baptized by American missionary Reverend Levi Chamberlain on December 23, 1893, and given the Christian name Lydia.

Liliuokalani‘s family was aliʻi nui, Hawaiian nobility, and were distantly related to the reigning House of Kamehameha, sharing common descent from Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku, King of the island of Hawaii and the great-grandfather of Kamehameha I, the first King of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Her father Caesar Kapaʻakea was a Hawaiian chief who served in the House of Nobles from 1845 until he died in 1866 and on the King’s Privy Council from 1846 – 1866. Her mother Analea Keohokālole, who was of a higher rank than her husband, was a Hawaiian chiefess and a member of the House of Nobles from 1841 to 1847, and on the King’s Privy Council 1846 to 1847.

Liliuokalani had six siblings who survived infancy:

Liliuokalani in 1853; Credit – Wikipedia

Liliuokalani was declared eligible to be in the line of succession by the royal decree of King Kamehameha III and therefore attended the Chiefs’ Children’s School, later known as Royal School, in Honolulu, which is still in existence as a public elementary school, the Royal Elementary School, the oldest school on the island of Oahu. Her classmates included the other children declared eligible to be in the line of succession including her siblings James Kaliokalani and the future King Kalākaua, and their thirteen royal relations including the future kings Kamehameha IV, Kamehameha V, and Lunalilo.

After her schooling was complete, Liliuokalani became a part of the young social elite during the reign of King Kamehameha IV (reigned 1855 – 1863). In 1856, when King Kamehameha IV announced that he would marry their classmate Emma Rooke, there were some at the Hawaiian court who thought that his bride should be Liliuokalani because she was his equal in birth and rank. However, Liliuokalani became a close friend of Queen Emma and was a maid of honor at Emma’s wedding and one of her ladies-in-waiting.

After a brief engagement to William Charles Lunalilo, the future Lunalilo, King of the Hawaiian Islands (reigned 1873 – 1874), Liliuokalani became romantically involved with the American-born John Owen Dominis, a staff member to Prince Lot Kapuāiwa, the future King Kamehameha V, and then a secretary to King Kamehameha IV. Born on March 10, 1832, in Schenectady, New York, John was the son of sea captain John Dominis, originally from Trieste, then part of the Austrian Empire, now in Italy, who emigrated to the United States, and American-born Mary Lambert Jones Dominis. In 1837, the couple relocated to the Kingdom of Hawaii with their son John. Liliuokalani and John had known each other from childhood. John attended a school next to the Royal School, would climb the fence to observe the princes and princesses, and became friends with them.

John Owen Dominis, Prince Consort of the Hawaiian Islands; Credit – Wikipedia

On September 16, 1862, Liliuokalani and John were married in an Anglican ceremony by Reverend Samuel Chenery Damon, a missionary to Hawaii and pastor of the Seamen’s Bethel Church in Honolulu. The couple moved into the Dominis residence, Washington Place in Honolulu. However, the marriage was not happy and was childless. John chose to socialize without Liliuokalani and his mother Mary Dominis looked down upon her non-caucasian daughter-in-law. Liliuokalani noted in her memoir that her mother-in-law considered her an “intruder” but became more affectionate in her later years.

Liliuokalani’s brother David (King Kalākaua); Credit – Wikipedia

On February 3, 1874, Lunalilo, King of the Hawaiian Islands (born William Charles Lunalilo) died from tuberculosis at the age of 39 without naming an heir. As King Lunalilo had wanted to make Hawaii more democratic, it is thought that he wished to have the people choose their next ruler. The Legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the people’s representatives, would choose the next monarch from the eligible royal family members. Queen Emma, the widow of King Kamehameha IV, claimed that King Lunalilo had wanted her to succeed him, but he died before a formal proclamation could be made. She decided to run in the election against Liliuokalni’s brother David who had lost to King Lunalilo in a similar election in 1873. While the Hawaiian people supported Emma, it was the legislature that elected the new monarch. They favored David who won the election 39 – 6. David reigned as King Kalākaua and became the first of two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaiian Islands from the House of Kalākaua, who were also the last two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Upon his accession to the throne, King Kalākaua (David) named his brother William Pitt Leleiohoku II as his heir apparent. When his brother died from rheumatic fever in 1877, King Kalākaua named his sister Liliuokalani as his heir apparent. She acted as regent during her brother’s absences from the country.

Liliuokalani (left) and Kapiʻolani (right) at the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria; Credit – Wikipedia

In April 1887, Liliuokalani, her husband John Owen Dominis, and her sister-in-law Queen Kapiʻolani were part of the delegation from the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands sent to attend the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in London. Kapiʻolani and Liliuokalani were granted an audience with Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace. They attended the special Jubilee service at Westminster Abbey and were seated with other foreign royal guests.

On November 25, 1890, Liliuokalani’s brother King Kalākaua sailed for California aboard the USS Charleston. The purpose of the trip was uncertain but there were reports that the trip was for his ill health. David arrived in San Francisco, California on December 5, 1890. He suffered a minor stroke in Santa Barbara, California, and was rushed back to San Francisco. Two days before his death, he lapsed into a coma. King Kalākaua died in San Francisco, California on January 20, 1891, aged 54. On January 29, 1891, in the presence of the cabinet ministers and the Supreme Court justices, the new Queen Liliuokalani took the oath of office to uphold the constitution and became the first and the only female monarch of the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands. Liliuokalani’s husband John Owen Dominis died less than a year later on August 27, 1891, at their Washington Place home and was buried in the Mauna Ala Royal Mausoleum in Honolulu.

In 1875, during the reign of Queen Liliuokalani’s brother, the Reciprocity Treaty, a free trade agreement between the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands and the United States, gave free access to the United States market for sugar and other products grown in the Kingdom of Hawaii. In return, Hawaii guaranteed the United States that it would not cede or lease any of its land to other foreign powers. Then in 1887, also during the reign of Queen Liliuokalani’s brother, a new constitution was proposed by anti-monarchists that would strip the absolute Hawaiian monarchy of much of its authority and transfer power to a coalition of American, European, and native Hawaiians. It became known as the Bayonet Constitution because of the armed militia that forced King Kalākaua to sign it or be deposed.

During her reign, Queen Liliuokalani attempted to draft a new constitution that would restore the power of the monarchy. Threatened by Queen Liliuokalani’s attempts to negate the Bayonet Constitution, in 1893, a group of local businessmen and politicians composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national overthrew Queen Liliuokalani and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii. The overthrow was supported by the landing of United States Marines to protect American interests, making the monarchy unable to protect itself. The Republic of Hawaii was established but the ultimate goal was the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the United States which would happen in 1898.

Liliʻuokalani being escorted up the steps of ʻIolani Palace, where she was imprisoned after the unsuccessful uprising of 1895; Credit – Wikipedia

In January 1895, a short, unsuccessful uprising to restore the monarchy was launched. On January 16, 1895, Liliuokalani was arrested and placed under house arrest at the ʻIolani Palace in Honolulu when firearms were found at her home, Washington Place, after a tip from a prisoner. On January 24, 1895, Liliuokalani was forced to abdicate, officially ending the monarchy. Liliuokalani was tried by the military commission of the new Republic of Hawaii and was sentenced to five years of hard labor in prison and fined $5,000. The sentence was commuted on September 4, 1895, to imprisonment in the ʻIolani Palace. On October 13, 1896, the Republic of Hawaii granted Liliuokalani a full pardon and restored her civil rights.

Cover of Liliuokalani’s song Aloha ʻOe, 1890; Credit – Wikipedia

After her pardon, Liliuokalani felt the need to leave Hawaii, at least for a while. From December 1896 through January 1897, Liliuokalani stayed in Brookline, Massachusetts with her late husband’s cousins William Lee and Sara White Lee of the Lee & Shepard Publishing House. William and Sara and Liliuokalani’s long-time friend Julius A. Palmer Jr. helped her compile and publish her book of Hawaiian songs and her memoir Hawaii’s Story by Hawaii’s Queen which gave her point of view of the history of her country and her overthrow. Liliuokalani’s most famous song is Aloha ʻOe or Farewell to Thee. It was originally written as a lover’s goodbye, but the song came to be regarded as a symbol of the loss of her country, the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands. It remains one of the most recognizable Hawaiian songs.

Washinton Place, Liliuokalani’s home in Honolulu; Credit – By Frank Schulenburg – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=146081316

At the end of her visit to Massachusetts, Liliuokalani began to divide her time between Hawaii and Washington, D.C., where she worked to plead her case to the United States. Unsuccessful attempts were made to restore the monarchy and oppose annexation and the United States formally annexed Hawaii as a territory in 1898. In 1909, Liliuokalani brought an unsuccessful lawsuit against the United States under the Fifth Amendment seeking the return of the Hawaiian Crown Lands. The American courts invoked an 1864 Kingdom of Hawaii Supreme Court decision over a case involving Dowager Queen Emma and King Kamehameha V. In this decision, the courts found that the Crown Lands were not necessarily the private possession of the monarch in the strictest sense of the term. In 1911, Liliuokalani was granted a lifetime pension of $1,250 a month by the Territory of Hawaii.

Queen Liliuokalani lying in state at Iolani Palace; Credit – Wikipedia

By 1917, her health was suffering. She lost the use of her legs and her mental capacity was severely diminished. On the morning of November 11, 1917, Liliʻuokalani died at the age of seventy-nine at her home, Washington Place in Honolulu, Hawaii. The former queen lay in state at Kawaiahaʻo Church for public viewing, after which she received a state funeral in the throne room of ‘Iolani Palace, on November 18, 1917. Composer Charles E. King led a youth choir in Aloha ʻOe as her coffin was moved to her burial place. The procession participants and the crowds of people along the route began to sing the song. Liliuokalani was interred with her family members in the Kalākaua Crypt on the grounds of the Royal Mausoleum of Mauna ʻAla in Honolulu, Hawaii.

The burial vault of Queen Liliuokalani in the Kalākaua Crypt; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

King Edward III of England, father of Sir John de Southeray; Credit – Wikipedia

Sir John de Southeray (circa 1364 – 1383) was the eldest of the three illegitimate children of King Edward III of England and his mistress Alice Perrers. Alice’s family surname was Salisbury and they worked as goldsmiths. Janyn Perrers, who would become Alice’s first husband, became an apprentice to the Salisbury family in 1342. It appears that around 1359, Janyn Perrers did some work for the royal court because in a royal writ he is described as “our beloved Janyn Perrers, our jeweler”. There is a possibility that he met King Edward III in his capacity as a goldsmith and jeweler and that Alice may have accompanied him.

Shortly after her husband died in 1361 or 1362, Alice became a lady-in-waiting to Philippa of Hainault, the wife of King Edward III. Even if Alice had not previously met King Edward III, they certainly became acquainted while she served as a lady-in-waiting. Alice, who was about 24 years old, gave birth to the first of her three children by Edward III in 1364, when the king was 56 years old.

King Edward III and Alice’s eldest child John had two younger sisters:

John had fourteen royal half-siblings from the marriage of his father King Edward III to Philippa of Hainault:

In January 1377, the nearly thirteen-year-old John married seventeen-year-old Maud de Percy, the daughter of Henry de Percy, 3rd Baron Percy. The marriage was childless and in 1380, Maud obtained an annulment, claiming to have been married to John without her consent. Later in 1377, on April 23, St. George’s Day, John was knighted by his father King Edward III at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, along with John’s ten-year-old nephews, the future King Richard II, and the future King Henry IV, who would usurp the throne from his cousin King Richard II in 1399. On June 17, 1377, four days before his death, King Edward III gave his illegitimate son John his own coat of arms. Upon the death of King Edward III, John’s nephew Richard, the son of the deceased Edward, Prince of Wales, the Black Prince, succeeded his grandfather as King Richard II.

From 1381 to 1382, Sir John de Southeray took part in the Fernandine Wars, a series of three wars between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Crown of Castile. He accompanied the English military expedition in support of Castile, commanded by his half-brother Edmund of Langley, 1St Duke of York. During the unsuccessful Castilian campaign, John led a contingent of English soldiers. After his troops went unpaid, John incited them to mutiny. Unlike his troops, John was never punished for his actions. John’s death date is uncertain. It is assumed he died in 1383, aged about nineteen. The last mention of Sir John de Southeray in contemporary chronicles is in 1383, when he asked a man named Ralph Basing to pay him a debt.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

The Hawaiian Islands, located in the Pacific Ocean, were originally divided into several independent chiefdoms. The Kingdom of Hawaii was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great of the independent island of Hawaii, conquered the independent islands of Oahu, Maui, Molokai, and Lanai, and unified them under one government and ruled as Kamehameha I, King of the Hawaiian Islands. In 1810, the whole Hawaiian archipelago became unified when Kauai and Niihau voluntarily joined the Kingdom of Hawaii. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom: the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

In 1778, British explorer James Cook visited the islands. This led to increased trade and the introduction of new technologies and ideas. In the mid-19th century, American influence in Hawaii dramatically increased when American merchants, missionaries, and settlers arrived on the islands. Protestant missionaries converted most of the native people to Christianity. Merchants set up sugar plantations and the United States Navy established a base at Pearl Harbor. The newcomers brought diseases that were new to the indigenous people including influenza, measles, smallpox, syphilis, tuberculosis, and whooping cough. At the time of James Cook’s arrival in 1778, the indigenous Hawaiian population is estimated to have been between 250,000 and 800,000. By 1890, the indigenous Hawaiian population had declined to less than 40,000.

In 1893, a group of local businessmen and politicians composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national overthrew Queen Liliuokalani, her cabinet, and her marshal, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii. This led to the 1898 annexation of Hawaii as a United States territory. On August 21, 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state of the United States.

In 1993, one hundred years after the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown, the United States Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Apology Resolution which “acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and further acknowledges that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaii or through a plebiscite or referendum”. As a result, the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom in Hawaii, was established along with ongoing efforts to redress the indigenous Hawaiian population.

********************

Kapiʻolani, Queen Consort of the Hawaiian Islands; Credit – Wikipedia

Kapiʻolani, Queen Consort of the Hawaiian Islands was the wife of Kalākaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands, who reigned from 1874 to 1891. Kapiʻolani Napelakapuokakaʻe was born on December 31, 1834, in Hilo on the island of Hawaii, then in the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands, now in the state of Hawaii. She was the eldest of the three daughters of High Chief Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole of Hilo and High Chiefess Kinoiki Kekaulike of Kauaʻi, the daughter of King Kaumualiʻi, the last king of an independent Kauaʻi. Kapiʻolani’s Christian name was Esther but unlike other Christian Hawaiian royals, she and her two sisters never used their Christian names. When Kapiʻolani was sixteen, she was sent to the royal court in Honolulu on the island of Oahu and was under the guardianship of King Kamehameha III. Kapiʻolani learned to understand a few English words and phrases but she never learned to speak English fluently and required a Hawaiian translator when communicating with English speakers.

Kapiʻolani had two younger sisters:

Kapiʻolani in 1852, the year she married Bennett Nāmākēhā; Credit – Wikipedia

On March 7, 1852, 17-year-old Kapiʻolani married 53-year-old High Chief Bennett Nāmākēhā, as his third wife. Bennett was a member of the House of Nobles and the uncle of Queen Emma, the wife of King Kamehameha IV. The marriage was childless but Kapiʻolani and Bennett were appointed the caretakers of Prince Albert Edward Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa a Kamehameha, the only child of Emma and King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma. Kapiʻolani also served as a lady-in-waiting to Queen Emma. Sadly, the young prince died in 1862, when he was four years old. Two years earlier, Kapiʻolani’s husband Bennett died on December 27, 1860, aged sixty-one.

David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Māhinulani Nālaʻiaʻehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua, (King Kalākaua); Credit – Wikipedia

On December 19, 1863, Kapiʻolani married David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Māhinulani Nālaʻiaʻehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua, the future King Kalākaua, who was only two years older than Kapiʻolani. Their marriage was childless. David’s family was aliʻi nui, Hawaiian nobility, and was distantly related to the reigning House of Kamehameha, sharing common descent from Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku, King of the island of Hawaii and the great-grandfather of Kamehameha I, the first King of the Kingdom of Hawaii. David’s father Caesar Kapaʻakea was a Hawaiian chief who served in the House of Nobles from 1845 until he died in 1866 and on the King’s Privy Council from 1846 – 1866. David’s mother Analea Keohokālole, who was of a higher rank than her husband, was a Hawaiian chiefess and a member of the House of Nobles from 1841 to 1847, and on the King’s Privy Council from 1846 to 1847. David was declared eligible to be in the line of succession by the royal decree of King Kamehameha III. He served in the House of Nobles, and the Privy Council of State and held many other court and government posts during the reigns of King Kamehameha IV, King Kamehameha V, and King Lunalilo.

On February 3, 1874, Lunalilo, King of the Hawaiian Islands (born William Charles Lunalilo) died from tuberculosis without naming an heir. As King Lunalilo had wanted to make Hawaii more democratic, it is thought that he wished to have the people choose their next ruler. The Legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the people’s representatives, would choose the next monarch from the eligible royal family members. Queen Emma, the widow of King Kamehameha IV, claimed that King Lunalilo had wanted her to succeed him, but he died before a formal proclamation could be made. She decided to run in the election against David who had lost to King Lunalilo in a similar election in 1873. While the Hawaiian people supported Emma, it was the legislature that elected the new monarch. They favored David who won the election 39 – 6. David reigned as King Kalākaua and became the first of two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaiian Islands from the House of Kalākaua, who were also the last two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

The Sisters of St. Francis and some of the residents of the home Kapiʻolani had built for the children of couples with leprosy; Credit – WIkipedia

As Queen, Kapiʻolani worked to improve the health of the Hawaiian people. She founded the Kapiʻolani Maternity Home in Honolulu, where Hawaiian mothers and their newborn babies could receive care. The Kapiʻolani Maternity Home is still in existence as the Kapiʻolani Medical Center for Women and Children, part of Hawaii Pacific Health’s network of hospitals. Kapiʻolani frequently visited Kakaʻako Branch Hospital on Oʻahu, which served as a receiving station for leprosy patients from all over the islands, and befriended the Roman Catholic Sisters of Saint Francis who staffed the hospital. On July 21, 1884, Kapiʻolani, along with her sister-in-law and her husband Princess Liliuokalani and John Owen Dominis, visited the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement on Molokaʻi where the now famous Belgian priest Father Damien (now Saint Damien of Molokai) spent sixteen years caring for the physical, spiritual, and emotional needs of those in the leper colony before he contracted leprosy. One of the concerns brought to the attention of Queen Kapiʻolani was the welfare of non-leprous children living on the island born to couples with leprosy. Kapiʻolani promised to build a home for these children. After the royal visit, the patients’ living conditions improved significantly.

Princess Liliuokalani (left) and Queen Kapiʻolani (right) at the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria; Credit – Wikipedia

In April 1887, Queen Kapiʻolani, along with her sister-in-law Princess Liliuokalani and her husband John Owen Dominis, were part of the delegation from the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands sent to attend the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in London. Kapiʻolani and Liliuokalani were granted an audience with Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace. They attended the special Jubilee service at Westminster Abbey and were seated with other foreign royal guests.

Queen Kapiʻolani kneeling at the coffin of her husband David (King Kalākaua); Credit – Wikipedia

On November 25, 1890, Kapiʻolani’s husband David set sail for California aboard the USS Charleston. The purpose of the trip was uncertain but there were reports that the trip was for his ill health. David arrived in San Francisco, California on December 5, 1890. He suffered a minor stroke in Santa Barbara, California, and was rushed back to San Francisco. Two days before his death, he lapsed into a coma. Kalākaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands, born David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Māhinulani Nālaʻiaʻehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua died in San Francisco, California on January 20, 1891, aged 54. He had been under the care of US Navy doctors who listed the cause of his death as nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys.

After the death of her husband and the accession of her sister-in-law Liliuokalani to the throne, Kapiʻolani retired from public life and rarely attended formal social events. Queen Liliuokalani ruled for two years before she was overthrown. In 1893, a group of local businessmen and politicians composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national overthrew Queen Liliuokalani, her cabinet, and her marshal, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii. This led to the 1898 annexation of Hawaii as a United States territory.

Tomb of Queen Kapiʻolani and her husband David (King Kalākaua); Credit – Wikipedia

Kapiʻolani lived out the remainder of her life at her private residence Pualeilani in Waikīkī, Honolulu, on the island of Oahu, where the Hyatt Regency Waikiki now stands. During the last two years of her life, Kapiʻolani suffered three strokes. She died, aged sixty-four, at her home on June 24, 1899. After a funeral at the Kawaiahaʻo Church in Honolulu officiated by the Anglican Bishop Alfred Willis, Kapiʻolani was buried in the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna ʻAla. Due to overcrowding, in 1907, the Territory of Hawaii allocated $20,000 for the construction of a separate underground vault for the Kalākaua family. Kapiʻolani’s coffin and the coffins of the Kalākaua family were transferred to the new underground Kalākaua Crypt in a ceremony on June 24, 1910, officiated by her sister-in-law, the former Queen Liliuokalani.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

Adam FitzRoy’s father King Edward II of England (in red) in a contemporary illustration; Credit – Wikipedia

Born circa 1307, possibly at Windsor Castle in Windsor, England, Adam FitzRoy was the illegitimate son of King Edward II of England and an unknown mother. His mother could have been one of the ladies or maids of his father’s second wife Margaret of France who was younger than her stepson Edward. Adam was probably born before his father succeeded to the throne in 1307 and certainly before his father married Isabella of France, daughter of King Philippe IV of France, in 1308. Adam’s surname FitzRoy comes from the Anglo-Norman Fitz, meaning “son of” and Roy, meaning “king”, implying the original bearer of the surname was a child of a king. Adam’s paternal grandparents were King Edward I of England and his first wife Eleanor of Castile.

Adam had four royal half-siblings from his father’s marriage with Isabella of France:

Adam is first mentioned in King Edward II’s wardrobe account of 1322: Ade filio domini Regis bastardo (Adam, bastard son of the lord king). Between June 6, 1322 and September 18, 1322, Adam was given a total of thirteen pounds and twenty-two pence to buy himself armatura et alia necessaria (armor and other necessaries) to participate in King Edward II’s campaign in Scotland planned for the autumn of 1322, in the First War of Scottish Independence (1296–1328) against the formidable Robert Bruce, King of Scots. Edward II had taken up arms against Robert the Bruce before. In 1314, he attempted to complete his father’s campaign in Scotland. This resulted in a decisive Scottish victory at the Battle of Bannockburn by a smaller army led by Robert the Bruce, King of Scots. In 1320, the Declaration of Arbroath was sent by a group of Scottish nobles to the Pope affirming Scottish independence from England.

Statue of Robert the Bruce in Stirling, Scotland; Credit – By Ally Crockford – Own work, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28842870

King Edward II assembled an army of about 23,000 men including his illegitimate son Adam who was probably about 15 -17 years old. Edward II and his army reached Edinburgh, Scotland, and plundered Holyrood Abbey. However, Robert the Bruce purposefully avoided battle with Edward II and lured his army inland. With the English army inland, the plans to supply the English army by sea failed and the English ran out of supplies and had to retreat to Newcastle, England. Many English soldiers became ill with dysentery and died. On September 18, 1322, the teenage Adam FitzRoy died, probably from dysentery. On September 30, 1322, Adam was buried at Tynemouth Priory in Tynemouth, England. His father King Edward II was unable to attend the funeral due to the continuation of his Scottish campaign. However, he paid for a silk coverlet with gold thread to cover the body of his son.

The ruins of Tynemouth Priory; Credit – By Agnete – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62804912

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2025

The Hawaiian Islands, located in the Pacific Ocean, were originally divided into several independent chiefdoms. The Kingdom of Hawaii was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great of the independent island of Hawaii, conquered the independent islands of Oahu, Maui, Molokai, and Lanai, and unified them under one government and ruled as Kamehameha I, King of the Hawaiian Islands. In 1810, the whole Hawaiian archipelago became unified when Kauai and Niihau voluntarily joined the Kingdom of Hawaii. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom: the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

In 1778, British explorer James Cook visited the islands. This led to increased trade and the introduction of new technologies and ideas. In the mid-19th century, American influence in Hawaii dramatically increased when American merchants, missionaries, and settlers arrived on the islands. Protestant missionaries converted most of the native people to Christianity. Merchants set up sugar plantations and the United States Navy established a base at Pearl Harbor. The newcomers brought diseases that were new to the indigenous people including influenza, measles, smallpox, syphilis, tuberculosis, and whooping cough. At the time of James Cook’s arrival in 1778, the indigenous Hawaiian population is estimated to have been between 250,000 and 800,000. By 1890, the indigenous Hawaiian population declined had to less than 40,000.

In 1893, a group of local businessmen and politicians composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national overthrew Queen Liliuokalani, her cabinet, and her marshal, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii. This led to the 1898 annexation of Hawaii as a United States territory. On August 21, 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state of the United States.

In 1993, one hundred years after the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown, the United States Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Apology Resolution which “acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and further acknowledges that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaii or through a plebiscite or referendum”. As a result, the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom in Hawaii, was established along with ongoing efforts to redress the indigenous Hawaiian population.

********************

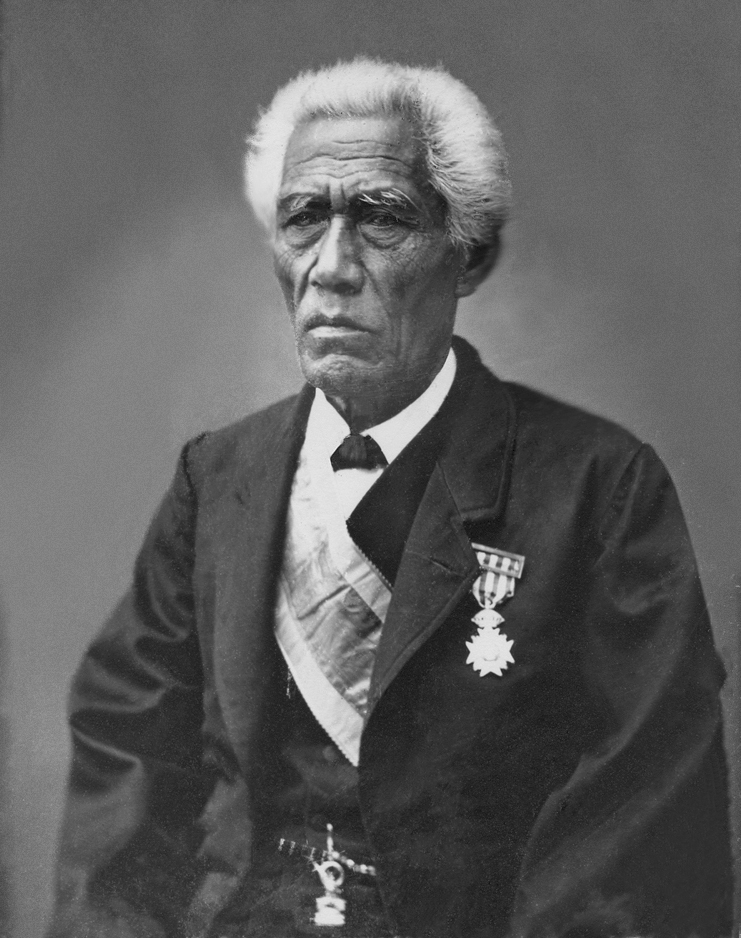

Kalākaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands; Credit – Wikipedia

Known for his patronage and the restoration of many Hawaiian cultural traditions, Kalākaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands from 1874 – 1891 was the first of the two monarchs of the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands from the House of Kalākaua. He was born David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Māhinulani Nālaʻiaʻehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua on November 16, 1836, in the grass hut compound of his maternal grandfather at the base of Punchbowl Crater in Honolulu, Kingdom of Hawaii now in the state of Hawaii. Known as David, he was the second eldest of the seven surviving children who survived infancy and the second of the three surviving sons of first cousins Caesar Kaluaiku Kamakaʻehukai Kahana Keola Kapaʻakea and Analea Keohokālole.

David’s family was aliʻi nui, Hawaiian nobility, and were distantly related to the reigning House of Kamehameha, sharing common descent from Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku, King of the island of Hawaii and the great-grandfather of Kamehameha I, the first King of the Kingdom of Hawaii. His father Caesar Kapaʻakea was a Hawaiian chief who served in the House of Nobles from 1845 until he died in 1866 and on the King’s Privy Council from 1846 – 1866. David’s mother Analea Keohokālole, who was of a higher rank than her husband, was a Hawaiian chiefess and a member of the House of Nobles from 1841 to 1847, and on the King’s Privy Council 1846 to 1847.

David had six siblings who survived infancy:

David, aged fourteen; Credit – Wikipedia

David was declared eligible to be in the line of succession by the royal decree of King Kamehameha III and therefore attended the Chiefs’ Children’s School, later known as Royal School, in Honolulu, which is still in existence as a public elementary school, the Royal Elementary School, the oldest school on the island of Oahu. His classmates included the other children declared eligible to be in the line of succession including his siblings James Kaliokalani and the future Queen Lydia Liliʻuokalani, and their thirteen royal relations including the future kings Kamehameha IV, Kamehameha V, and Lunalilo. Following his formal schooling, David studied law under Charles Coffin Harris, a New England lawyer who became a politician and judge in the Kingdom of Hawaii. David would appoint Harris as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Hawaii in 1877. David held various military, government, and court positions that provided him with much experience for his future role as King of the Hawaiian Islands.

David’s wife Queen Kapiʻolani; Credit – Wikipedia

On December 19, 1863, David married Kapiʻolani Napelakapuokakaʻe, the daughter of High Chief Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole of Hilo and High Chiefess Kinoiki Kekaulike of Kauaʻi, the daughter of King Kaumualiʻi, the last king of an independent Kauaʻi. Kapiʻolani was the widow of High Chief Bennett Nāmākēhā, the uncle of King Kamehameha IV’s wife Queen Emma, and served as Queen Emma’s lady-in-waiting, and Prince Albert Edward Kamehameha‘s nurse and caretaker, the only child of King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma who died when he was four years old. David and Kapiʻolani’s marriage was childless.

On February 3, 1874, Lunalilo, King of the Hawaiian Islands (born William Charles Lunalilo) died from tuberculosis at the age of 39 without naming an heir. As King Lunalilo had wanted to make Hawaii more democratic, it is thought that he wished to have the people choose their next ruler. The Legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the people’s representatives, would choose the next monarch from the eligible royal family members. Queen Emma, the widow of King Kamehameha IV, claimed that King Lunalilo had wanted her to succeed him, but he died before a formal proclamation could be made. She decided to run in the election against David who had lost to King Lunalilo in a similar election in 1873. While the Hawaiian people supported Emma, it was the legislature that elected the new monarch. They favored David who won the election 39 – 6. David reigned as King Kalākaua and became the first of two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaiian Islands from the House of Kalākaua, who were also the last two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Upon his accession to the throne, David named his brother William Pitt Leleiohoku II as his heir apparent. When his brother died from rheumatic fever in 1877, David changed the name of his sister Lydia Dominis to Liliuokalani and named her as his heir apparent. She acted as regent during her brother’s absences from the country, and after his death, she became the last monarch of Hawaii.

During David’s reign, the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, a free trade agreement between the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands and the United States greatly benefitted Hawaii. The treaty gave free access to the United States market for sugar and other products grown in the Kingdom of Hawaii. In return, Hawaii guaranteed the United States that it would not cede or lease any of its land to other foreign powers. The treaty led to large investment by Americans in sugarcane plantations in Hawaii. At a later time, an additional clause was added to the treaty allowing the United States exclusive use of land in the area known as Puʻu Loa, which was later used for the American Pearl Harbor naval base. David’s extravagant expenditures and his plans for a Polynesian confederation gave power to the annexationists who were already working toward a United States takeover of Hawaii, which would happen during the reign of David’s sister Queen Liliuokalani. In 1887, David was pressured to sign a new constitution that made the monarchy little more than a figurehead position.

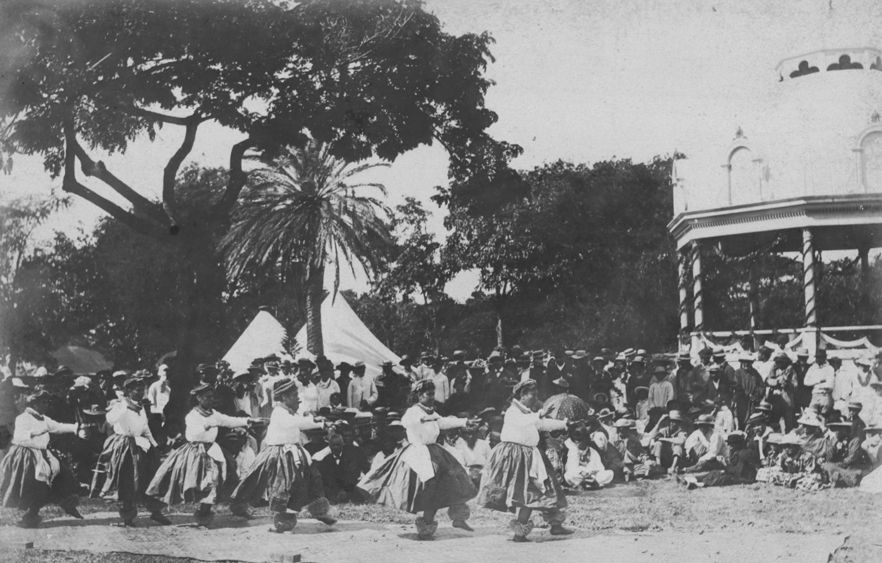

The hula being danced at David’s 49th birthday celebrations; Credit – Wikipedia

During the earlier reigns of Christian converts, dancing the hula was forbidden and punishable by law. Gradually Hawaiian monarchs began to allow the hula but it was David who brought it back in full force. David encouraged Hawaiians with knowledge of the old songs and chants to participate in events and arranged for musicologists to observe and document the old songs and chants. Called the “Merrie Monarch” for his patronage of the arts and the restoration of many Hawaiian cultural traditions during his reign, David is honored by the Merrie Monarch Festival, an annual week-long cultural festival in Hilo, Hawaii, held the week after Easter.

David (in white slacks) aboard the USS Charleston en route to San Francisco; Credit – Wikipedia

On November 25, 1890, David sailed for California aboard the USS Charleston. The purpose of the trip was uncertain but there were reports that the trip was for his ill health. David arrived in San Francisco, California on December 5, 1890. He suffered a minor stroke in Santa Barbara, California, and was rushed back to San Francisco. Two days before his death, he lapsed into a coma. Kalākaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands, born David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Māhinulani Nālaʻiaʻehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua died in San Francisco, California on January 20, 1891, aged 54. He had been under the care of US Navy doctors who listed the cause of his death as nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys.

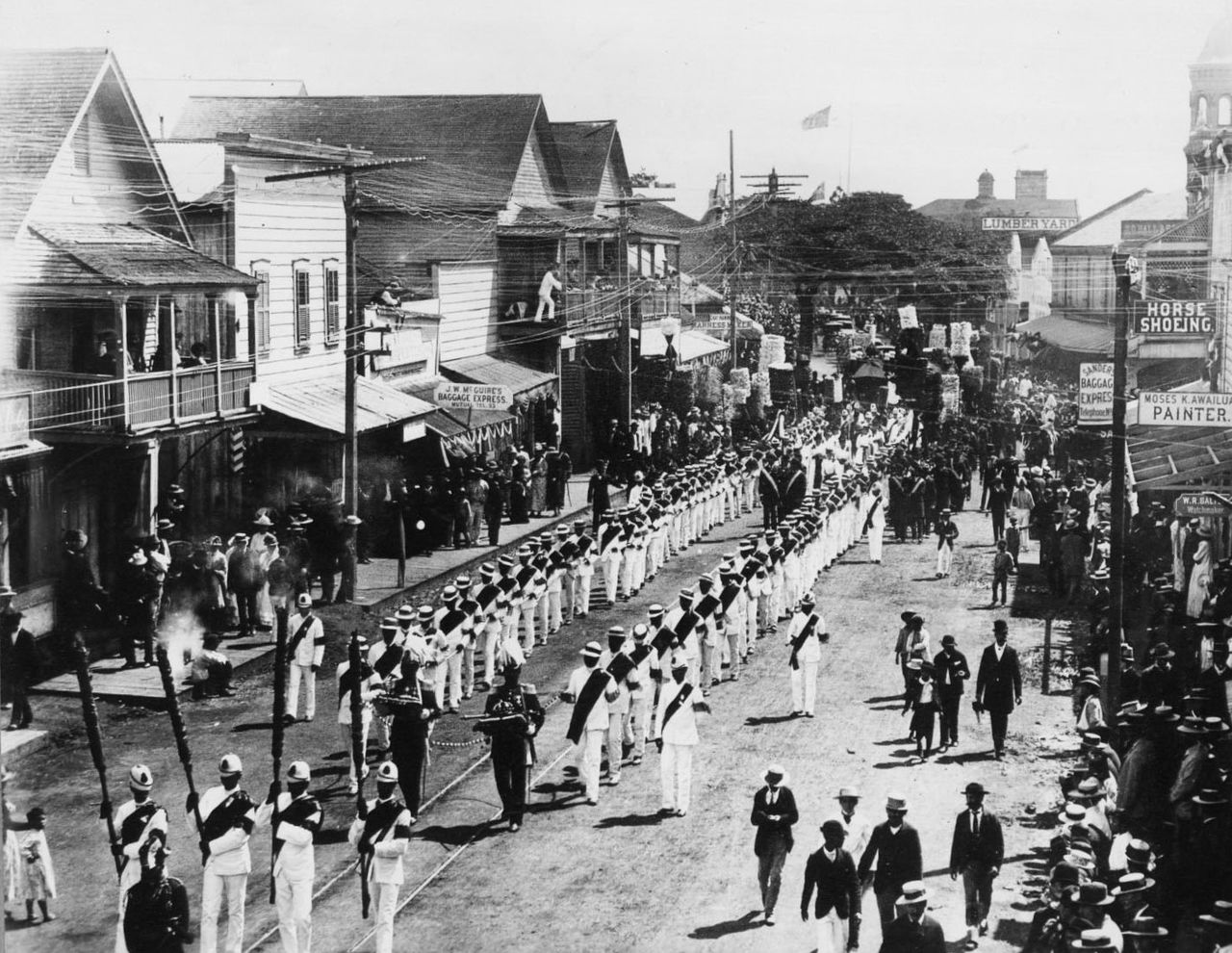

Funeral Procession; Credit – Wikipedia

News of David’s death did not reach Hawaii until January 29, 1891, when the USS Charleston returned to Hawaii with his remains. His sister Liliuokalani ascended to the throne of the Queen of the Hawaiian Islands the same day. After a state funeral, David was buried in the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna ʻAla on February 15, 1891.

Tomb of David and his wife; Credit – Wikipedia

Due to overcrowding, in 1907, the Territory of Hawaii allocated $20,000 for the construction of a separate underground vault for the Kalākaua family. David’s coffin and the coffins of the Kalākaua family were transferred to the new underground Kalākaua Crypt in a ceremony on June 24, 1910, officiated by his sister, the former Queen Liliuokalani.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

Richard FitzRoy’s father King John of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Richard FitzRoy, born circa 1185/1186, was the illegitimate son of King John of England and Ela de Warenne. His surname FitzRoy comes from the Anglo-Norman Fitz, meaning “son of” and Roy, meaning “king”, implying the original bearer of the surname was a child of a king. Richard was also called Richard de Chilham and Richard de Dover. His paternal grandparents were King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Richard’s maternal grandparents were Hamelin de Warenne, Earl of Surrey and Isabel de Warenne, 4th Countess of Surrey, one of the wealthiest heiresses in England.

Richard’s maternal grandfather Hamelin de Warenne, originally Hamelin of Anjou, was the illegitimate son of Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou who was married to Empress Matilda, Lady of the English, the only surviving child of King Henry I of England. Geoffrey and Matilda were the parents of King Henry II of England so therefore Hamelin was the elder half-brother of King Henry II, and the uncle to Henry II’s children including King Richard I and King John.

Richard’s royal half-siblings (l to r) Henry, Richard, Isabella, Eleanor, and Joan; Credit – Wikipedia

King John had several long-term mistresses and around twelve illegitimate children, Richard’s half-siblings. Richard had five royal half-siblings from his father’s marriage to Isabella of Angoulême, Countess of Angoulême in her own right:

Before May 11, 1214, Richard married Rohese de Dover, the only child and heiress of Fulbert II de Dover and Isabel de Briwere of Devon. Through his marriage, Richard received Chilham Castle in Chilham, Kent, England and about a dozen fiefs in Kent and Essex, and became 1st Baron of Chilham.

Richard and Rohese had three children:

Battle of Sandwich, showing the capture of the French flagship & the killing of Eustace the Monk; Credit – Wikipedia

During the First Barons’ War (1215 – 1217), when a group of barons, with the support of King Philippe II of France, rebelled against Richard’s father King John of England, Richard supported his father as one of the commanders of the royal army. On August 24, 1217, during the naval Battle of Sandwich, Richard, in command of a ship, attacked and captured the French flagship and personally killed Eustace the Monk, the commander of the French fleet. Richard’s father King John died on October 19, 1216, and was succeeded by his nine-year-old son King Henry III of England. The First Barons’ War continued after King John’s death, but the great William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, who served four English kings – Henry II, Richard I, John, and Henry III – managed to get most barons to switch sides from working with France to the new King Henry III and attacking the French.

Richard was the constable of several castles including the important Wallingford Castle in Berkshire, England, and served as Sheriff of Berkshire. He took part in the Fifth Crusade during the successful Siege of Damietta (1218 – 1219) in Egypt and then returned to England. In 1223, Richard accompanied his half-brother King Henry III on a campaign in Wales, and in 1225 he accompanied Alexander II, King of Scots, who was married to his half-sister Joan of England, on his pilgrimage to Canterbury.

In May 1230, King Henry III organized a campaign attempting to regain some of the Norman and Angevin French ancestral territories that his father had lost, and Richard accompanied his half-brother. The campaign did not go well. Henry III made a truce with King Louis X of France and returned to England having achieved nothing but a costly fiasco. After that, Richard had a career in royal service, mostly in command of castles on the Welsh border.

St. Mary’s Church and Churchyard in Chilham, Kent, England; Credit – www.findagrave.com

Richard FitzRoy, died before June 24, 1246, aged around sixty, at Chilham Castle in Chilham, Kent, England. All that is left of the Norman castle is the keep. A manor house, also called Chilham Castle, was built on the property in 1616 and still exists. It is thought that Richard was buried at St. Mary’s Churchyard in Chilham, Kent, England.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

The Hawaiian Islands, located in the Pacific Ocean, were originally divided into several independent chiefdoms. The Kingdom of Hawaii was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great of the independent island of Hawaii, conquered the independent islands of Oahu, Maui, Molokai, and Lanai, and unified them under one government and ruled as Kamehameha I, King of the Hawaiian Islands. In 1810, the whole Hawaiian archipelago became unified when Kauai and Niihau voluntarily joined the Kingdom of Hawaii. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom: the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

In 1778, British explorer James Cook visited the islands. This led to increased trade and the introduction of new technologies and ideas. In the mid-19th century, American influence in Hawaii dramatically increased when American merchants, missionaries, and settlers arrived on the islands. Protestant missionaries converted most of the native people to Christianity. Merchants set up sugar plantations and the United States Navy established a base at Pearl Harbor. The newcomers brought diseases that were new to the indigenous people including influenza, measles, smallpox, syphilis, tuberculosis, and whooping cough. At the time of James Cook’s arrival in 1778, the indigenous Hawaiian population is estimated to have been between 250,000 and 800,000. By 1890, the indigenous Hawaiian population declined had to less than 40,000.

In 1893, a group of local businessmen and politicians composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national overthrew Queen Liliʻuokalani, her cabinet, and her marshal, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii. This led to the 1898 annexation of Hawaii as a United States territory. On August 21, 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state of the United States.

In 1993, one hundred years after the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown, the United States Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Apology Resolution which “acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and further acknowledges that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaii or through a plebiscite or referendum”. As a result, the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom in Hawaii, was established along with ongoing efforts to redress the indigenous Hawaiian population.

********************

Lunalilo, King of the Hawaiian Islands; Credit – Wikipedia

Lunalilo, King of the Hawaiian Islands reigned for a little more than a year, from January 8, 1873, until his death on February 3, 1874. Born William Charles Lunalilo (the name William will be used in this article) on January 31, 1835, at the ʻIolani Palace in Honolulu, Oahu, Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands, now in the state of Hawaii, he was the only surviving child of the two children, both sons, of High Chief Charles Kanaʻina and Chiefess Miriam Auhea Kekāuluohi. He was given the name William in honor of King William IV of the United Kingdom. William’s elder brother Davida died in early childhood.

William’s parents; Credit – Wikipedia

William’s father Charles Kanaʻina, a great-great-grandson of King Kamehameha I, was an aliʻi, a hereditary noble of the Kingdom of Hawaii, and served on both the Privy Council and the House of Nobles. His mother Miriam Auhea Kekāuluohi was one of the many wives and also a niece of King Kamehameha I. She had also married King Kamehameha II before he converted to Christianity and gave up all but one wife.

Nicknamed Prince Bill, William was declared eligible to be in the line of succession by the royal decree of King Kamehameha III. He attended the Chiefs’ Children’s School, later known as Royal School, in Honolulu, which is still in existence as a public elementary school, the Royal Elementary School, the oldest school on the island of Oahu. William learned both Hawaiian and English. He loved English literature, especially the soliloquies from the plays of William Shakespeare. He was being prepared to assume the Governorship of the island of Oahu.

William as a teenager, circa 1850 – 1852; Credit – Wikipedia

Before 1860, the Kingdom of Hawaii used the British “God Save the King” as its national anthem. In 1860, King Kamehameha IV sponsored a contest for a new national anthem. He wanted a song with Hawaiian lyrics set to the tune of the British anthem. William wrote the winning entry “E Ola Ke Aliʻi Ke Akua” and donated his monetary winnings to the Queen’s Hospital founded by King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma in Honolulu. It remained the national anthem until it was replaced by Queen Liliʻuokalani’s composition “He Mele Lāhui Hawaiʻi”. See the Hawaiian and English lyrics at Wikipedia: E Ola Ke Aliʻi Ke Akua.

William never married. He was betrothed to marry his cousin Princess Victoria Kamāmalu but her brothers King Kamehameha IV and King Kamehameha V refused to allow her to marry William because their children would outrank the House of Kamehameha in the mana, the supernatural force that permeates the universe. William briefly courted Liliʻuokalani, the future Queen Regnant of Hawaii, but she broke off their relationship on the advice of King Kamehameha IV. During William’s reign as king, it was proposed that he marry Queen Emma, the widow of King Kamehameha IV, but this came to naught due to Queen Emma’s devotion to her late husband.

King Kamehameha V, known by his given name Lot, never married. He named his sister Princess Victoria Kamāmalu as his heir but she died in 1866 and Lot never named another successor. As he lay dying on December 11, 1872, his forty-second birthday, he offered the throne to his cousin Bernice Pauahi Bishop but she refused, and he died an hour later without naming his successor. Because of this, the Legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom chose the next monarch from the eligible royal family members. Lot’s cousin William Charles Lunalilo, a Kamehameha by birth from his mother, became the first elected King of the Hawaiian Kingdom and reigned as Lunalilo, King of the Hawaiian Islands.

Painting of King Lunalilo (William) by Danish painter Eiler Jurgensen, currently hangs at Iolani Palace. Purchased by the Kingdom of Hawaii government in 1882 from the estate of Charles Kana’ina, William’s father; Credit – Wikipedia

On January 9, 1873, William’s investiture ceremony was held at the Kawaiahaʻo Church in Honolulu, then the national church of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the church of the Hawaiian royal family, popularly known as Hawaii’s Westminster Abbey. Because William’s popularity was so great, and because he became king through a democratic process, he became known as “The People’s King”. William wanted to make the Hawaiian government more democratic and to improve the Hawaiian economy. He had many ideas and plans but nothing was accomplished due to his short reign.

Lunalilo Mausoleum on the grounds of Kawaiahaʻo Church in Honolulu, Hawaii; Credit – Wikipedia

William had suffered from tuberculosis since childhood and was an alcoholic which further exacerbated his health. On February 3, 1874, he died from tuberculosis at the age of 39, at Haimoeipo, his private residence in Honolulu. On his deathbed, William requested to be buried on the grounds of the Kawaiahaʻo Church, saying he wanted to be “entombed among my people, rather than the kings and chiefs” at the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii in Honolulu. On November 23, 1875, his coffin was taken from the Royal Mausoleum, where it had rested temporarily awaiting the completion of the Lunalilo Mausoleum, to the completed tomb on the grounds of Kawaiahaʻo Church in Honolulu.

Interior of Lunalilo Mausoleum with William’s tomb in the center and the tomb of his father Charles Kanaʻina on the right; Credit – Wikipedia

Like his predecessor, William died without naming an heir. As William had wanted to make Hawaii more democratic, it is thought that he wished to have the people choose their next ruler. The Legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the people’s representatives, would choose the next monarch from the eligible royal family members. Queen Emma, the widow of King Kamehameha IV, claimed that William had wanted her to succeed him, but he died before a formal proclamation could be made. She decided to run in the election against David Kalākaua who had lost to William in a similar election in 1873. While the Hawaiian people supported Emma, it was the legislature that elected the new monarch. They favored David Kalākaua, who won the election 39 – 6 and became the first of two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaiian Islands from the House of Kalākaua, who were the last two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Works Cited

by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

Drawing of William Longespée from his effigy in Salisbury Cathedral; Credit – Wikipedia

Born circa 1176, William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury was the illegitimate son of King Henry II of England and his former royal ward and then mistress Ida de Tosny. His surname Longespée probably refers to William’s height and the oversized weapons he used. William’s paternal grandparents were Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine and Empress Matilda, Lady of the English, the only surviving legitimate child of King Henry I of England. His maternal grandparents were Ralph de Tosny, V, Lord of Flamstead (in Hertfordshire, England) and Margaret de Beaumont. Henry II had several long-term mistresses and around twelve illegitimate children, William’s half-siblings.

13th-century depiction of William’s royal half-siblings, (l to r) William, Young Henry, Richard, Matilda, Geoffrey, Eleanor, Joan, and John; Credit – Wikipedia

William had eight royal half-siblings from his father’s marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine:

William’s mother Ida de Tosny married Roger Bigod, 2nd Earl of Norfolk and the couple had at least eight children, William’s half-siblings:

William’s father King Henry II of England; Credit – Wikipedia

King Henry II acknowledged William as his son but little is known about William’s childhood. According to William’s own statements, he grew up at times with Hubert de Burgh, later Earl of Kent and Chief Justiciar of England and Ireland during the reigns of King John and his son and successor King Henry III. In 1188, when William came of age, his father gave him the town of Appleby in Lincolnshire, England.

In 1196, William married a great heiress Ela of Salisbury, 3rd Countess of Salisbury, the only child of William FitzPatrick, 2nd Earl of Salisbury, and Eléonore de Vitré. Earlier in 1196, Ela’s father died and she succeeded to her father’s title as 3rd Countess of Salisbury in her own right. After the marriage, William became the 3rd Earl of Salisbury by Jure uxoris, by right of his wife. Because Ela was only eleven years old, the couple did not have children for several years.

William and Ela had at least nine children:

Effigy of William’s half-brother King Richard I; By Adam Bishop – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17048652

William participated in the campaigns (1193 – 1198) of his half-brother King Richard I of England in the Duchy of Normandy (now in France) to recover the land seized by King Philippe II of France while Richard was participating in the Third Crusade. William was closest in age to King John, the youngest of his father’s legitimate children, who succeeded to the English throne in 1199. During King John’s reign, William was at court on important ceremonial occasions and held several positions: High Sheriff of Wiltshire, Lieutenant of Gascony, Constable of Dover, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, Lord Warden of the Welsh Marches, and Sheriff of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire.

Effigy of William’s half-brother King John; Credit – Wikipedia

William was a commander during the 1210 – 1212 Welsh and Irish campaigns of his half-brother King John of England and participated in the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. In 1213, he led the English fleet in the Battle of Damme in which the English seized or destroyed a good portion of the French fleet. On July 27, 1214, William commanded the right flank of an English coalition army against France at the Battle of Bouvines, the last battle of the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. The battle ended in defeat for the English coalition and capture for William when the priest-soldier Philippe de Dreux, Bishop of Beauvais threw a mace at his head. William was unhorsed and taken prisoner and the English soldiers fled. Because of the resounding French victory, all the Norman and Angevin French ancestral territories, Normandy, Maine, Touraine, Anjou, and Poitou, were lost forever to the English crown.

While King John was trying to save his French territories, his discontented English barons led by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, were protesting John’s continued misgovernment of England. The result of this discontent was the best-known event of John’s reign, the Magna Carta, the “great charter” of English liberties, forced from King John by the English barons and sealed at Runnymede near Windsor Castle on June 15, 1215. Among the liberties were the protection of church rights, protection for the barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limitations on feudal payments to the Crown.

William had returned to England during King John’s troubles with the English barons and was one of the few barons who was loyal to John. Infuriated by being forced to agree to the Magna Carta, John turned to Pope Innocent III, who declared the Magna Carta null and void and the rebel barons excommunicated. The conflict between John and the barons was transformed into an open civil war, the First Barons’ War (1215 – 1217). William was one of the leaders of King John’s army in the south of England. However, the rebel barons appealed to King Philippe II of France, and offered his son, the future King Louis VIII of France, the English crown. After Louis of France landed in England as an ally of the rebel barons, William went over to the rebel side because he thought John’s cause was lost.

William’s half-brother King John died of dysentery on October 19, 1216. He was succeeded by his nine-year-old son King Henry III of England. The First Barons’ War continued after King John’s death, but the great William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, who served four English kings – Henry II, Richard I, John, and Henry III – managed to get most barons to switch sides from Louis of France to the new King Henry III and attack Louis. The Magna Carta was reissued in King Henry III’s name with some of the clauses omitted and was sealed by the nine-year-old king’s regent William Marshal. William Longespée supported his nephew King Henry III and held an influential place in the government during the young king’s minority.

William’s tomb in Salisbury Cathedral; Credit – By Bernard Gagnon – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7140363

In 1225, returning to England from Gascony (now in France), William was shipwrecked off the coast of Brittany (now in France). He spent several months in a monastery on the French island of Île de Ré. Shortly after returning to England, William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury, aged about fifty, died on March 7, 1226, at his home, Salisbury Castle in Salisbury, Wiltshire, England which was part of Old Sarum and no longer exists. He was buried at Salisbury Cathedral where he had laid the foundation stones in 1220.

William’s wife Ela never remarried. Three years after William’s death, Ela founded Lacock Abbey in Lacock, Wiltshire, England. In 1238, she entered Lacock Abbey as a nun and was Abbess from 1240 – 1257. Ela survived her husband William by thirty-five years, dying on August 24, 1261, aged about seventy-three, and was buried in Lacock Abbey.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

Jesus Washing Peter’s Feet by Ford Madox Brown; Credit – Wikipedia

The Royal Maundy Service is held on Maundy Thursday, also called Holy Thursday, the Thursday before Easter and the day before Good Friday. It is the day during Holy Week that commemorates the Last Supper of Jesus Christ with the Apostles and Jesus washing of the feet of the Apostles, known as Maundy from Old French mandé and from Latin mandatum meaning “command”. The root of the practice of washing the feet is found in the hospitality customs of ancient civilizations, especially where sandals were the usual footwear. A host would provide water for guests to wash their feet, provide a servant to wash the feet of the guests, or even serve the guests by washing their feet. The traditional Maundy of washing feet is still observed in many Christian denominations. Today, the Royal Maundy Service involving the British monarch no longer involves foot washing. Instead, the monarch gives small silver coins known as Maundy Money as symbolic alms to elderly people. The only traces of the washing of the feet at the modern Royal Maundy Service are the nosegays, small flower bouquets, traditionally with the stems bound by doilies, and the linen towels worn by several officials.

********************

History of the Royal Maundy Service

The Royal Maundy Service in 1867 at the Chapel Royal, Whitehall during the reign of Queen Victoria. Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford, represented Queen Victoria; Credit – Wikipedia

On April 15, 1210, King John (reigned 1199 – 1216) became the first recorded English monarch to distribute alms to the poor at a Maundy service when he gave clothes, forks, food, and other gifts to the poor of Knaresborough, Yorkshire, England. In 1213, King John also became the first recorded English monarch to give gifts of small silver coins to the poor when he gave gifts of thirteen pence to thirteen poor men at a ceremony in Rochester Cathedral. The number thirteen represented those at the Last Supper, Jesus and the Twelve Apostles. By 1363, during the reign of King Edward III (reigned 1327 – 1377), the monarch gave gifts of pence but also washed the feet of the recipients. King Henry IV (reigned 1399 – 1413) was the first monarch to decree that the number of pence given be determined by the monarch’s age.

Queen Elizabeth II and The Duke of Edinburgh with the traditional nosegays in 2005; Credit – Wikipedia

When washing the feet, the monarch used scented water to hide any unpleasant odors from the poor. In addition, the feet were washed three times before the monarch washed the feet, once by a servant and twice by court officials. In later years, sweet-smelling nosegays were used to hide odors and the nosegays are still carried today during the Royal Maundy Service. During the years when the plague was running rampant, the monarch did not attend the Royal Maundy Service. Instead, the Lord High Almoner attended, washed the feet, and distributed the alms.

The Catholic Queen Mary I (reigned 1553 – 1558) and her Protestant half-sister Queen Elizabeth I (reigned 1558 – 1603) both participated in elaborate Royal Maundy Services. In 1556, Mary washed the feet of forty-one poor women, one for each year of her age while “ever on her knees”, and gave each woman forty-one pence, along with gifts of bread, fish, and clothing. She also donated her gown to the poorest woman. In 1572, Elizabeth gave each woman £1 instead of gifting her gown because she disliked seeing the women trying to grab a piece of the royal gown.

King Charles I (reigned 1625 – 1649), who was beheaded resulting in the monarchy being replaced by the Commonwealth of England, rarely attended the Royal Maundy Service. After the Restoration in 1660, when the monarchy was restored, King Charles I’s son King Charles II (reigned 1660 – 1685) attempted to gain popularity by always attending the Royal Maundy Service. He even attended during the plague years of 1661 and 1663. His brother and successor King James II (reigned 1685 – 1688) also attended the services during his reign. King William III (reigned jointly with his wife and first cousin Queen Mary II, the daughter of King James II) attended the Royal Maundy Service in 1685. Pre-1725 records are vague and there is no record of any monarch attending the service from 1698 to 1932. However, over those years, the Lord High Almoner continued to attend and represent the monarch.

In the early 20th century, members of the royal family sometimes attended the Royal Maundy Service. Queen Alexandra, the wife of King Edward VII (reigned 1901 – 1910) attended twice. Most Royal Maundy Services during the first part of the 20th century were attended by Princess Helena, the fifth child, and third daughter of Queen Victoria, or Princess Helena’s daughter Princess Marie Louise. In 1931, Princess Marie Louise attended the Royal Maundy Service and suggested that her first cousin King George V (reigned 1910 – 1936) distribute the gifts the following year. King George did so in 1932, the only time he attended the service during his reign.

In January 1936, King George V died and his son King Edward VIII attended the Royal Maundy Service that year. King Edward VIII abdicated the throne in December 1936 and was succeeded by his brother King George VI (reigned 1936 – 1952). King George VI attended the Royal Maundy Service only twice during his reign in 1940 and 1944. He was represented at the services during the other years of his reign by the Lord High Almoner, Cosmo Gordon Lang, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Queen Elizabeth II (reigned 1952 – 2022) attended all but five Royal Maudy Services during her seventy-year-reign. She missed two services following childbirth and two services because she was on official visits to Commonwealth countries. In 2022, the year of the death of the 95-year-old Queen Elizabeth II, she was represented at the service by her son then The Prince of Wales and her daughter-in-law then The Duchess of Cornwall. Due to COVID, two services during the reign of Queen Elizabeth II (2020 and 2021) were canceled but the gifts of coins were mailed to the recipients.

King Charles III‘s first Royal Maundy Service as king took place at York Minster on April 6, 2023, and he was accompanied by Queen Camilla. After the announcement in February 2024 that King Charles III was temporarily stepping back from royal duties following a cancer diagnosis, he was represented by Queen Camilla at the 2024 service at Worcester Cathedral.

********************

Royal Maundy Service Sites

1877 Royal Maundy Service at the Chapel Royal, Whitehall. A Yeoman of the Guard carrying the Maundy Money on a silver dish; Credit – Wikipedia

For the monarch’s convenience, the Royal Maundy Service was usually held in or near London. After 1714, when the monarch no longer attended, the Royal Maundy Service was held at the renovated Chapel Royal, Whitehall in the former Banqueting Hall, the only part of the Palace of Whitehall to survive a fire in 1698, until the chapel was given to the Royal United Services Institute.

From 1890 – 1954, the service was held at Westminster Abbey, London except for years when there was a coronation. Because Westminster Abbey had to be closed for the coronation preparations, the Royal Maundy Service was held at St. Paul’s Cathedral, London during the coronation years. From 1954 to 1970, the service was held in even-numbered years at Westminster Abbey and in odd-numbered years at cathedrals throughout the United Kingdom. Since 1970, the Royal Maundy Service has been held at different churches, usually a cathedral, throughout the United Kingdom. Queen Elizabeth II had directed that the service be held in London only once every ten years. However, during the last years of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, the Royal Maundy Service was held or scheduled to be held at St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle or Westminster Abbey in London for the convenience of the elderly Queen Elizabeth II.

********************

The Royal Maundy Gifts

Preparing the Maundy Money in 1932

Currently, the gift recipients are pensioners, retired people, one man and one woman for each year the monarch has lived including the year the monarch is currently living. They are chosen from various Christian churches for their service to their churches and communities. The gift recipients attend a Maundy Lecture so they will be familiar with the Royal Maundy Service. Until the joint reign of King William III and Queen Mary II (1689 – 1694), the gift recipients were poor people of the same gender as the monarch. During the the joint reign of King William III and Queen Mary II, each monarch made gifts to poor people of their gender but after Queen Mary II died in 1694, only men received gifts from King William III who reigned alone until he died in 1702. Beginning with the reign of King George I (1714 – 1727), both men and women have received gifts, with each gender in a number coinciding with the monarch’s age and each recipient receiving that number of pence. The gifts of food and clothing were eventually discontinued and replaced by monetary allowances. In 1837, when 71-year-old King William IV died and was succeeded by his 18-year-old niece Queen Victoria caused a large drop in the number of gift recipients.

Maundy Money from the 2023 service; Credit – Royal Maundy 2023 www.royal.uk

Today, each gift recipient receives two small leather purses, one red and one white. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, the red purse contained a total of £5.50, symbolizing the monarch’s gift of food and clothing once presented: £1 representing the money for the redemption of the monarch’s gown, £3 in place of the clothing, and £1.50 in place of the food. However, in 2023, the first Royal Maundy service during the reign of King Charles II, the red purse contained two commemorative coins, one to mark the King’s upcoming 75th birthday, the other to mark the 75th anniversary of the arrival of West Indian workers on the Empire Windrush and their contribution to multi-racial Britain.

Maundy Money from the 2023 service; Credit – Royal Maundy 2023 www.royal.uk

The white purse contains the Maundy coins equivalent in pence to the monarch’s age. The coins are legal tender but recipients usually consider them as a keepsake. At the 2023 Royal Maundy Service, the new Maundy coins using the official coinage portrait of King Charles III by Martin Jennings made their debut.

King Charles III’s official Maundy Money; Credit – The Royal Mint

********************

The Royal Maundy Service

King Charles III and Queen Camilla with the traditional nosegays, enter York Minster for their first Royal Maundy Service as King and Queen (2023)

After being greeted at the door of the church by the clergy, the monarch is presented with the traditional nosegay and then proceeds up the nave of the church.

The Yeomen of the Guard carrying the Maundy Money

The purses containing the Maundy Money are carried into the church by the Yeomen of the Guard on six silver dishes, held above their heads. Although the exact origin of this custom is uncertain, historians have speculated that it is related to earlier times when food was distributed to the gift recipients and that the dishes were held high to prevent premature grabbing of the food. The six silver dishes date from the reign of King Charles II (reigned 1660 – 1685) and are part of the Royal Regalia which is kept at the Jewel House of the Tower of London when not in use.

King Charles III and Queen Camilla at the 2023 Royal Maundy Service at York Minster in York, England

The Order of Service for Royal Maundy is short and simple. It begins with the reading of the Gospel of John 13:34, “A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another.” The second reading from the Gospel of Matthew 25: 35-36, says: “For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me.”

King Charles III distributing the Maundy Money in 2023

The monarch distributes half the gifts after the first reading, and the other half after the second reading. During the gift distribution, the Chapel Royal Choir and the local choir sing anthems, concluding with George Frideric Handel‘s magnificent coronation anthem Zadok the Priest. The Royal Maundy Service concludes with prayers, the blessing and the singing of God Save the King.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

********************

Works Cited