by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2023

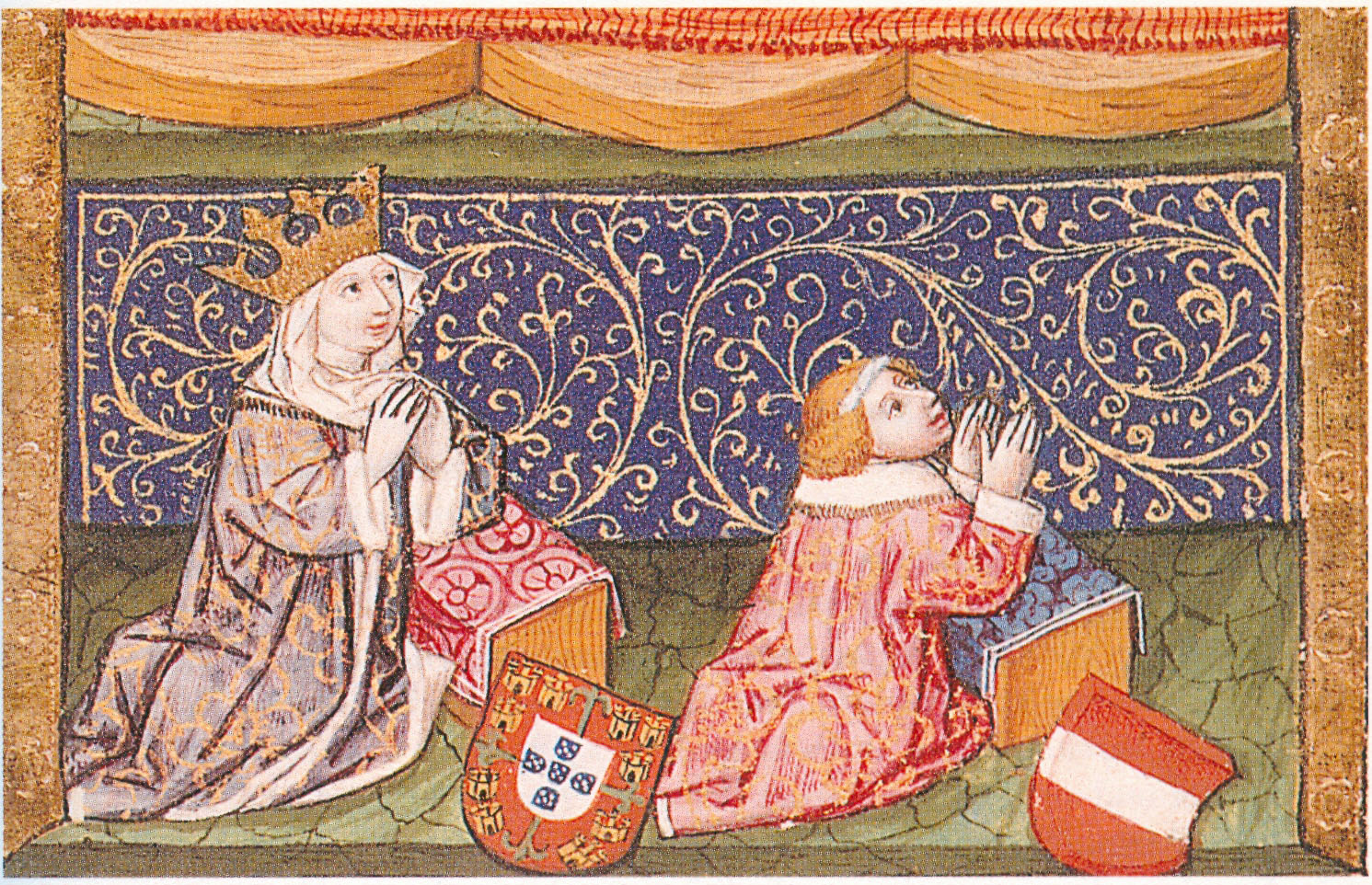

Maria Bianca Sforza; Credit – Wikipedia

The Holy Roman Empire was a limited elective monarchy composed of hundreds of kingdoms, principalities, duchies, counties, prince-bishoprics, and Free Imperial Cities in central Europe. The Holy Roman Empire was not really holy since, after Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1530, no emperors were crowned by the pope or a bishop. It was not Roman but rather German because it was mainly in the regions of present-day Germany and Austria. It was an empire in name only – the territories it covered were mostly independent each with its own rulers. The Holy Roman Emperor directly ruled over only his family territories, and could not issue decrees and rule autonomously over the Holy Roman Empire. A Holy Roman Emperor was only as strong as his army and alliances, including marriage alliances, made him, and his power was severely restricted by the many sovereigns of the constituent monarchies of the Holy Roman Empire. From the 13th century, prince-electors, or electors for short, elected the Holy Roman Emperor from among the sovereigns of the constituent states.

Frequently but not always, it was common practice to elect the deceased Holy Roman Emperor’s heir. The Holy Roman Empire was an elective monarchy. No person had a legal right to the succession simply because he was related to the current Holy Roman Emperor. However, the Holy Roman Emperor could and often did, while still alive, have a relative (usually a son) elected to succeed him after his death. This elected heir apparent used the title King of the Romans.

********************

Bianca Maria Sforza was the third wife of the three wives of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria. Born in Pavia, Duchy of Milan, now in Italy, on April 5, 1472, she was the third of the four children and the elder of the two daughters of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, 5th Duke of Milan and his second wife Bona of Savoy. Bianca Maria’s paternal grandparents were Francesco Sforza, 4th Duke of Milan, and her namesake Bianca Maria Visconti. Her maternal grandparents were Ludovico I, Duke of Savoy and Anne de Lusignan of Cyprus.

Bianca Maria had three siblings:

- Gian Galeazzo Sforza, 6th Duke of Milan (1469 – 1494), married his first cousin Isabella of Naples, had four children

- Hermes Maria Sforza, Marquis of Tortona (1470 – 1503), unmarried

- Anna Maria Sforza (1476 – 1497), married Alfonso I d’Este, later Duke of Ferrara, died in childbirth

Bianca Maria’s father was notorious for being cruel, tyrannical, and vengeful. On December 26, 1476, when Bianca Maria was four-years-old, her 32-year-old father was stabbed to death while attending Mass at the Church of Santo Stefano in Milan by three high-ranking officials of the Milanese court. Bianca Maria’s father was succeeded by his 7-year-old son Gian Galeazzo Sforza, 6th Duke of Milan with his mother Bona serving as Regent of Milan. However, in 1481, in a power play, the young Duke’s paternal uncle Ludovico Sforza forced Bona to resign her position as Regent. Ludovico quickly gained power and became the de facto ruler of the Duchy of Milan. Ludovico imprisoned his nephew Gian Galeazzo and later became 7th Duke of Milan after Gian Galeazzo’s death, which was widely viewed as suspicious.

In 1476, at the age of four, Bianca Maria married her 11-year-old first cousin Philibert I, Duke of Savoy, who died from tuberculosis at the age of 17. After the death of Philbert, 10-year-old Bianca Maria returned to Milan, where she was placed under the care of her paternal uncle Ludovico Sforza. Ludovico placed little value on Bianca Maria’s education, so she was ill-educated and free to do whatever she wanted.

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria

After the death of his beloved first wife Mary, Duchess of Burgundy in her own right and a second very short annulled marriage in name only to Anne, Duchess of Brittany in her own right, Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria decided to marry for a third time to Bianca Maria Sforza. The marriage was arranged by Bianca Maria’s uncle Ludovico Sforza, who wanted recognition and the title of Duke of Milan to be confirmed by Maximilian. To make the marriage more desirable to Maximilian, Ludovico offered a dowry of 400,000 ducats in cash and a further 40,000 ducats in jewels. Twenty-one-year-old Bianca Maria and thirty-four-year-old Maximilian were married by proxy on November 30, 1493, in the Duchy of Milan. Bianca Maria then traveled with her large dowry and large escort to Innsbruck, County of Tyrol, now in Austria. However, because Maximilian was dealing with a Turkish invasion of his Duchy of Styria, Bianca had to wait until March 16, 1494, to marry Maximilian in person.

The marriage was not a happy one. Maximilian complained that Bianca Maria may have been more beautiful than his first wife Mary of Burgundy, but she was not as intelligent. He considered Bianca Maria uneducated, talkative, naive, careless, and wasteful with money. Bianca Maria had a miscarriage shortly after her marriage and it seems that she was never able to conceive again. She was a stepmother to the two surviving children of Maximilian and his first wife Mary of Burgundy. They were relatively close in age to Bianca Maria and she very much liked them.

Bianca Maria’s stepchildren:

- Philip IV, Duke of Burgundy (1478 – 1506), also called Philip of Habsburg and Philip the Handsome, married Juana I, Queen of Castile and León, Queen of Aragon, had six children, all were kings or queen consorts

- Margaret of Austria, Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands (1480 – 1530), married (1) Juan of Aragon, Prince of Asturias, the only son and heir of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, no children, died from tuberculosis (2) Philibert II, Duke of Savoy, no children

After 1500, Maximilian lost all interest in Bianca Maria. She lived with her own court of 150 – 200 people from Milan, traveling to various castles. Maximilian did not allow Bianca Maria to control her own finances and so she seemed to be living in luxury one day and in poverty the next day. Bianca Maria’s court was arranged around the Roman Catholic church feasts with lavish celebrations at Easter, Christmas, Pentecost, and Corpus Christi. Carnivals, dances, tournaments, music, theater, hunting, and fishing were integral parts of Bianca Maria’s court life.

The Abbey Church at Stams Abbey where Bianca Maria is buried; Credit – Di Zairon – Opera propria, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50155281

In the last years of her life, Bianca Maria suffered from a debilitating illness, and died on December 31, 1510, aged 38, in Innsbruck, County of Tyrol, now in Austria. Maximilian was not in Innsbruck at the time of her death and did not return to attend her funeral. Bianca Maria was buried at the Abbey Church in the Crypt of the Princes of Tyrol at Stams Abbey (link in Italian) in Stams, County of Tyrol, one of Maximilian’s lands, now in Austria. Traditionally, a gilded statue of those interred in the Crypt of the Princes of Tyrol was placed in the crypt but no gilded statue or any type of memorial was ever made for Bianca Maria. She is only memorialized in the Hofkirche (Court Church) in Innsbruck where her bronze statue is one of twenty-eight statues on Maximilian’s cenotaph that depicts twenty-four events in Maximilian’s life. The Hofkirche and the cenotaph were built by Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I as a memorial to his grandfather Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. One has to doubt that Bianca Maria would have been included if Maximilian had designed his own cenotaph.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Abbazia di Stams (2021) Wikipedia (Italian). Available at: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbazia_di_Stams (Accessed: 13 May 2023).

- Bianca Maria Sforza (2023) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bianca_Maria_Sforza (Accessed: 13 May 2023).

- Bianca Maria Sforza (2022) Wikipedia (German). Available at: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bianca_Maria_Sforza (Accessed: 13 May 2023).

- Flantzer, Susan. (2023) Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria, Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/maximilian-i-holy-roman-emperor-duke-of-styria-carinthia-and-carniola-archduke-of-austria/ (Accessed: 13 May 2023).

- Wheatcroft, Andrew. (1995) The Habsburgs. London: Viking.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2016) Heart of Europe – A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.