by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2023

Mary of Waltham, Duchess of Brittany from King Edward III’s tomb in Westminster Abbey; Credit – Wikipedia

Mary of Waltham, Duchess of Brittany was born on October 10, 1344, at Bishop’s Waltham Palace in Bishop’s Waltham, Hampshire, England. During the reign of the House of Plantagenet, their children were often identified by their place of birth, and so Mary was called “of Waltham”. Mary was the ninth of the fourteen children and the fourth of the five daughters of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. Her paternal grandparents were King Edward II of England and Isabella of France. Joan’s paternal grandparents were Willem I, Count of Hainault (also Count of Holland, Count of Avesnes, and Count of Zeeland) and Joan of Valois.

Mary had thirteen siblings. Her brothers married into the English nobility and it was their descendants who later battled for the throne in the Wars of the Roses.

- Edward, Prince of Wales, the Black Prince (1330 – 1376), married Joan, 4th Countess of Kent, had issue (King Richard II of England)

- Isabella of England (1332 – 1379) married Enguerrand VII de Coucy, 1st Earl of Bedford, had issue

- Joan of England (1333/1334 – 1348), died of the plague on the way to marry Pedro of Castile

- William of Hatfield (born and died 1337)

- Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence (1338 – 1368), married (1) Elizabeth de Burgh, 4th Countess of Ulster, had issue (2) Violante Visconti, no issue

- John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (1340 – 1399), married (1) Blanche of Lancaster, had issue including King Henry IV of England (2) Infanta Constance of Castile, had issue (3) Katherine Swynford (formerly his mistress), had issue

- Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York (1341 – 1402), married (1) Infanta Isabella of Castile, had issue (2) Joan Holland, no issue

- Blanche of the Tower (born and died March 1342)

- Margaret of Windsor (1346 – 1361), married John Hastings, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, no issue

- Thomas of Windsor (1347 – 1348), died of the plague

- William of Windsor (born and died 1348), died of the plague

- Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester (1355 – 1397), married Eleanor de Bohun, had issue

Woodstock Palace; Credit – Wikipedia

The family’s main home was Woodstock Palace in Oxfordshire, England. It was the favorite residence of Mary’s mother Philippa and the birthplace of several of her children. In her early years, Mary was raised in the household of Sir William de St. Omer, Lord of Brundale, and his wife Elizabeth. It was common for royal and noble children to be raised for a period of time in another household.

John IV, Duke of Brittany (right) jousting with Mary’s brother Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester (left); Credit – Wikipedia

Mary was well-acquainted with her future husband John IV, Duke of Brittany because he had been raised in King Edward III’s household. During a succession dispute in the Duchy of Brittany, now in France, King Edward III supported John of Monfort, John IV’s father. During the Hundred Years’ War between England and France, a close alliance with Brittany would give the English troops access to ports in Brittany. When John of Montfort was captured at the Siege of Rennes, during the War of the Breton Succession, his wife Joanna of Flanders, received military support from King Edward III. In return, Joanna promised her son John would marry one of Edward III’s daughters. In 1342, Joanna of Flanders brought her three-year-old son to England and left him with King Edward III for safety, and so the future John IV, Duke of Brittany was raised in the royal nursery. When Mary was born in 1344, she was regarded as the future bride of John. Her sisters were older than John and already betrothed. When John’s father died in 1345, he inherited the Duchy of Brittany and King Edward III became his guardian. Mary and John spent their childhood together

16-year-old Mary and 22-year-old John were married at Woodstock Palace in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, England around July 3, 1361. There is no account of the wedding but it is known that tailor John Avery created a wedding dress, a gift from King Edward III, consisting of a tunic and a mantle made from two types of cloth of gold. The mantle was trimmed with 600 minivers and 40 ermines, gifts from King Jean II of France.

Mary and John remained at the English court after their marriage. Arrangements were being made for them to leave England and reside in Brittany as the Duke and Duchess of Brittany. However, within weeks, Mary became quite ill, and she died sometime before September 13, 1361, because on that date a clerk of the royal court paid 200 pounds “for the expenses of the burial of Madame Mary, daughter of the King, Duchess of Brittany”. Sadly, Mary’s 15-year-old younger sister Margaret, Countess of Pembroke died unexpectedly a few weeks later, after October 1, 1361, the last date there is a record that she was living. Mary and her sister Margaret were buried at Abingdon Abbey in Abingdon, Oxfordshire, England. Abingdon Abbey was dissolved in 1538, during the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the reign of King Henry VIII. Nothing of Abingdon Abbey remains.

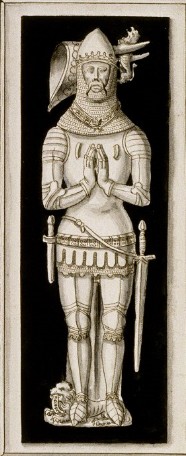

Drawing of the effigy on John’s tomb: Credit – Wikipedia

Mary’s widower John IV, Duke of Brittany married two more times and both wives had an English connection. In 1366, John married Lady Joan Holland (1350 – 1384), daughter of Thomas Holland, 1st Earl of Kent and Joan of Kent, 4th Countess of Kent, a granddaughter of King Edward I of England and the mother of King Richard II of England from her third marriage to Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of King Edward III of England. John and Joan Holland had no children. In 1386, John married Joan of Navarre (1370 – 1437), daughter of King Charles II of Navarre and Joan of Valois. John and Joan of Navarre had nine children. John IV, Duke of Brittany died on November 1, 1399, aged 60, in Nantes, Duchy of Brittany, now in France. He was buried at Nantes Cathedral. After John’s death, his widow Joan of Navarre became the second wife of King Henry IV of England.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Flantzer, Susan. (2015) King Edward III of England, Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-edward-iii-of-england/ (Accessed: November 24, 2022).

- John IV, Duke of Brittany (2022) Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_IV,_Duke_of_Brittany (Accessed: November 27, 2022).

- Mary of Waltham (2022) Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_of_Waltham (Accessed: November 27, 2022).

- Мария Плантагенет (2022) Wikipedia (Russian). Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%8F_%D0%9F%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B3%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%82 (Accessed: November 27, 2022).

- Mortimer, Ian. (2006) The Perfect King: The Life of Edward III, Father of the English Nation. London: Vintage Books.

- Weir, Alison. (1989) Britain’s Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. London: Vintage Books.

- Williamson, David. (1996) Brewer’s British Royalty: A Phrase and Fable Dictionary. London: Cassell.