by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2022

Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, detail from the frontispiece of the illuminated manuscript Talbot Shrewsbury Book; Credit – Wikipedia

Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York was a claimant to the English throne, the leader of the Yorkist faction during the Wars of the Roses, the father of King Edward IV of England and King Richard III of England, and the great-grandfather of King Henry VIII of England and his sister Margaret Tudor. Through Margaret Tudor, Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York is an ancestor of the British royal family and many other European royal families.

Born on September 21, 1411, Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York was the youngest of the three children and the only surviving son of Richard of Conisbrough, 3rd Earl of Cambridge and his first wife Anne Mortimer. Both Richard’s parents were descendants of King Edward III of England. Richard’s paternal grandparents were Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York (son of King Edward III), and Isabella of Castile (daughter of King Pedro of Castile and León). His maternal grandparents were Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March (a great-grandson of King Edward III) and Eleanor Holland (a great-great-granddaughter of King Edward I of England).

The White Rose of the House of York; Credit – Wikipedia

The House of York, a cadet branch of the House of Plantagenet, descended from two sons of King Edward III: in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, the fourth surviving son of Edward III and a female line of Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, Edward III’s second surviving son. These two lines came together when Richard’s mother Anne Mortimer, a great-granddaughter of Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence married Richard’s father Richard of Conisbrough, a son of Edmund of Langley, Duke of York. (A House of York family tree can be seen at Wikipedia: House of York.)

Richard had two elder siblings:

- Isabel of Cambridge (1409 – 1484), married (1) Sir Thomas Grey, had one son (2) Henry Bourchier, 1st Earl of Essex, had eleven children

- Henry of Cambridge, died in infancy

Richard’s mother Anne Mortimer died shortly after his birth, due to childbirth complications. His father Richard of Conisbrough made a second marriage to Maud Clifford, the divorced wife of John Neville, 6th Baron Latimer, and daughter of Thomas de Clifford, 6th Baron de Clifford, but the couple did not have any children.

In 1414, Richard’s father Richard of Conisbrough was created 3rd Earl of Cambridge but the title came without the usual grants of land. As a result, Richard of Conisbrough lacked the resources to properly equip himself for King Henry V’s invasion of France. Perhaps partly for this reason, Richard of Conisbrough conspired with Henry Scrope, 3rd Baron Scrope of Masham and Sir Thomas Grey to depose King Henry V and place Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, the brother of Richard of Conisbrough’s deceased wife Anne Mortimer on the English throne. Edmund Mortimer was the great-grandson of Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, the second surviving son of King Edward III, and his claim to the throne was superior to the claim of King Henry V and his father King Henry IV (both descended from King Edward III’s third surviving son John of Gaunt,1st Duke of Lancaster) who had deposed his first cousin King Richard II. However, Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March had not been aware of the plot and when he found out about it, he told King Henry V. The three plotters, including Richard of Conisbrough, were arrested, tried, and beheaded in August 1415.

Richard, 3rd Duke of York, stained glass window from St Laurence’s Church in Ludlow, Shropshire, England; Credit – http://www.richardiiiworcs.co.uk/

With the execution of his father, four-year-old Richard was an orphan. The title of Richard’s father was not attainted – after being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason), an act of attainder deprived nobles of their titles and lands. The descendants of the attainted noble could no longer inherit his lands or income. Because his father was not attainted, four-year-old Richard inherited his father’s Earl of Cambridge title. Three months later, little Richard’s paternal uncle (his father’s elder brother) Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York was killed at the Battle of Agincourt, and Richard inherited his paternal uncle’s titles and estates. In 1425, when Richard’s maternal uncle Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March died, Richard inherited the lesser title of Earl of March but the greater estates of the Mortimer family along with their claim to the English throne. Richard of York already held a strong claim to the English throne as a male-line great-grandson of King Edward III.

Richard’s wife Cecily Neville, Detail from the 15th century Neville Book of Hours. The rest of the image shows her mother, Joan Beaufort, along with her daughters; Credit – Wikipedia

After his father died in 1415, the orphaned Richard became a royal ward and was placed in the household of Sir Robert Waterton, loyal to King Henry V and King Henry VI of the House of Lancaster. In 1423, Richard became the royal ward of Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland who married (his second wife) Joan Beaufort, daughter of King Edward III’s fourth son John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and his mistress Katherine Swynford, whom he later married in 1396. Ralph Neville had eight children with his first wife and fourteen children with his second wife and had many daughters needing husbands. As was his right, Neville betrothed his youngest child, nine-year-old daughter Cecily Neville to thirteen-year-old Richard in 1424. Richard and Cecily were married by October 1429.

Richard and Cecily had twelve children including two Kings of England:

- Anne of York (1439 – 1476), married (1) Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter, had one daughter (2) Sir Thomas St. Leger, Anne died giving birth to a daughter

- Henry of York (born and died 1441), died in infancy

- Edward IV, King of England (1442 – 1483), married Elizabeth Woodville, had ten children including the ill-fated Edward V, King of England and Elizabeth of York, wife of Henry VII, King of England

- Edmund, Earl of Rutland (1443 – 1460), unmarried killed at the Battle of Wakefield, during the Wars of the Roses

- Elizabeth of York (1444 – circa 1503), wife of John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, had eleven children

- Margaret of York (1446 – 1503), married Charles I (the Bold), Duke of Burgundy, no children

- William of York (born and died 1447), died in infancy

- John of York (born and died 1448), died in infancy

- George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence (1449 – 1478), married Isabel Neville, had four children, George was executed by his brother King Edward IV

- Thomas of York (born and died circa 1450/1451), died in infancy

- Richard III, King of England (1452 – 1485), married Anne Neville, had one son Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales who predeceased his father, Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field

- Ursula of York (born and died 1455), died in infancy

In 1422, 35-year-old King Henry V succumbed to dysentery, a disease that killed more soldiers than battle, leaving his nine-month-old son to inherit his throne as King Henry VI. Over the next decade, Richard was a member of the close circle around the young king, in recognition of his place in the line of succession to the English throne. Richard was third in the line of succession after John, 1st Duke of Bedford and Humphrey, 1st Duke of Gloucester, both brothers of King Henry V and paternal uncles of the young King Henry VI. Richard was knighted by John, 1st Duke of Bedford in 1426. He was present for King Henry VI’s coronation at Westminster Abbey in 1429. Richard came of age in 1432 and was granted full control of his estates. In 1433, he was created a Knight of the Garter.

After the deaths of John, 1st Duke of Bedford in 1435 and Humphrey, 1st Duke of Gloucester in 1447, who were both childless, Richard, 3rd Duke of York was the heir to the English throne. In 1436, Richard was appointed to succeed John, 1st Duke of Bedford as commander of the English forces in France during the Hundred Years’ War. In 1445, King Henry VI married Margaret of Anjou, the niece of King Charles VII of France. Henry VI and Margaret had one child, born eight years after their marriage, Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales. Edward was the heir to the throne, followed by Richard, 3rd Duke of York.

King Henry VI of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Shortly before his son was born, King Henry VI had some sort of mental breakdown. He was unable to recognize or respond to people for over a year. These attacks may have been hereditary. Henry’s maternal grandfather King Charles VI of France suffered from similar attacks, even thinking he was made of glass. Sometimes Henry VI also had hallucinations which makes some modern medical experts think he may have had a form of schizophrenia. Porphyria, which may have afflicted King George III, has also been suggested as a possible cause. During Henry’s incapacity, Richard, 3rd Duke of York and the next in line to the throne after Henry’s son, governed as Lord Protector. Richard often quarreled with the Lancastrians at court. In 1448, he assumed the surname Plantagenet and then assumed the leadership of the Yorkist faction in 1450.

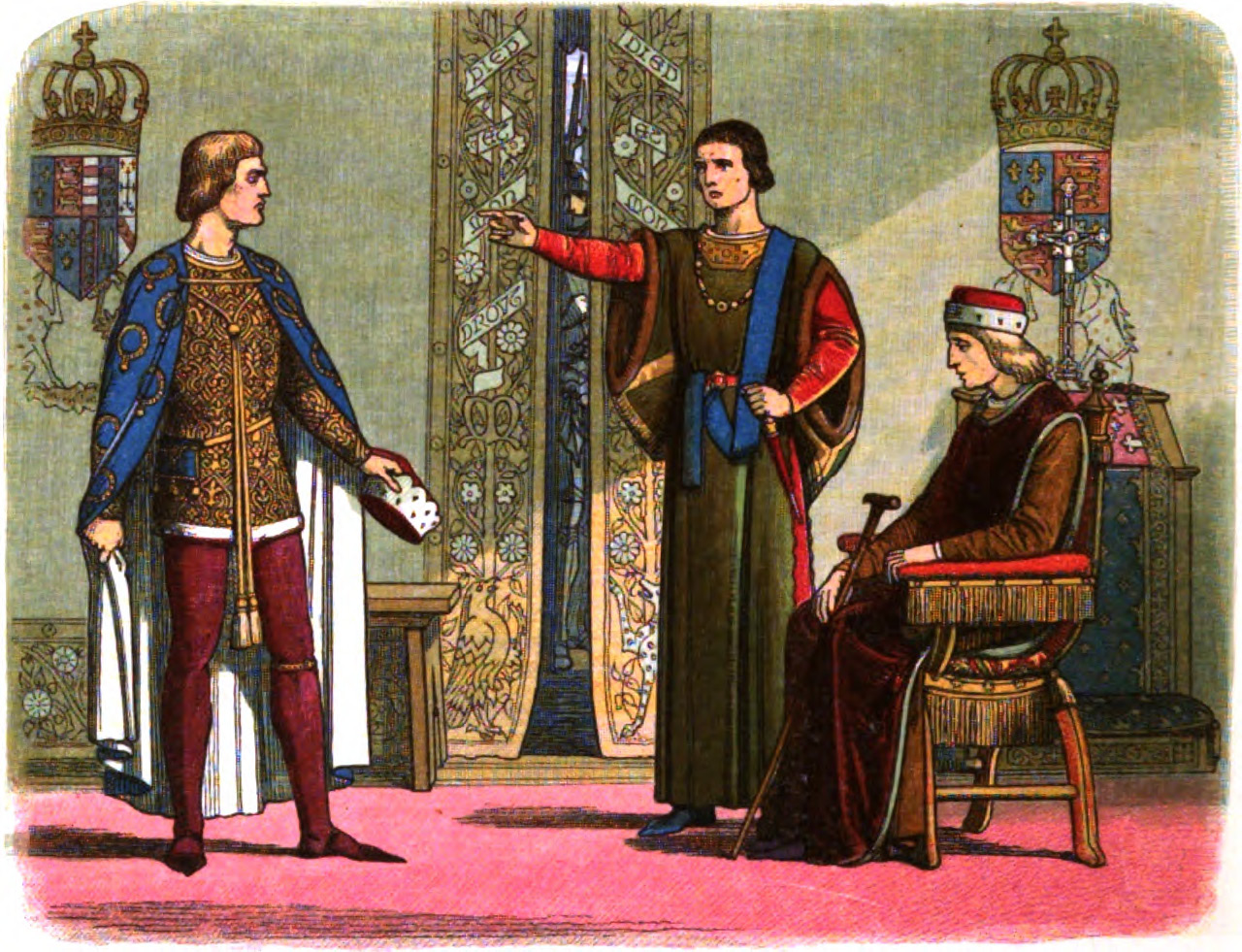

King Henry VI sitting while Richard, 3rd Duke of York (left) & Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset (center) argue. From a 19th-century book A Chronicle of England: B.C. 55 – A.D. 1485; Credit – Wikipedia

Even before the birth of Henry VI’s son, factions were forming and the seeds of the Wars of the Roses were being planted. There were differing opinions over how England should conduct the Hundred Years’ War with France. By the early 1450s, the most important rivalry was between Richard, 3rd Duke of York and Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset. Richard argued for a more vigorous approach to the war to recover territories lost to the French. The Duke of Somerset was among those who believed there should be attempts to secure peace by making concessions.

Richard, 3rd Duke of York and Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset also came from two rival cadet branches of the House of Plantagenet. In 1399, Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Lancaster, the eldest legitimate son of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (the third surviving son of King Edward III), deposed his first cousin King Richard II, the son of King Edward III’s eldest son Edward (Prince of Wales) the Black Prince. Henry Bolingbroke became King Henry IV, the first of three kings (along with Henry V and Henry VI) from the House of Lancaster. This bypassed the descendants of King Edward III’s second son Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence, with Richard, 3rd Duke of York of the House of York being the current heir of Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence. Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset was a member of the House of Lancaster. He was the grandson of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and his mistress Katherine Swynford, who John of Gaunt eventually married. Originally illegitimate, the Beauforts had been made legitimate by an Act of Parliament but were supposedly barred from the line of succession to the throne. However, there was always the possibility that this could be circumvented. See a family tree, Wikipedia: Family connections and the Wars of the Roses.)

King Henry VI was more interested in religion and learning than military matters. His wife Margaret of Anjou, an intelligent, energetic woman, realized that she would have to take on most of her husband’s duties. Margaret took over the military reins and aligned herself with Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset. Margaret believed her husband was threatened with being deposed by Richard, 3rd Duke of York who thought he had a better claim to the throne and would be a better king than Henry VI. After Henry VI’s recovery in 1455, Richard was dismissed from his position of Lord Protector, and Margaret and Edward Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset became all-powerful. Eventually, things came to a head between Henry VI’s House of Lancaster and Richard’s House of York, and war broke out.

At the First Battle of St. Albans on May 22, 1455, Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset was killed. Afterward, there was a peace, but hostilities started again four years later. On July 10, 1460, King Henry VI was captured at the Battle of Northampton and forced to recognize Richard, 3rd Duke of York as his heir instead of his own son.

The remains of Sandal Castle; Credit – By Abcdef123456 at English Wikipedia – Photo taken by Abcdef123456; Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.; description page is/was here., CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4380982

In December 1460, Richard, 3rd Duke of York rode to his fortress of Sandal Castle near Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England. He planned to spend a comfortable Christmas among his own people. Richard settled down to wait for his eldest son Edward, Earl of March (the future King Edward IV) to arrive from Shrewsbury with reinforcements before engaging with the Lancastrians. Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of Somerset and Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland, leading the Lancastrian army would have liked to besiege Richard at Sandal Castle but lacked the resources to conduct a siege. They decided that Richard must somehow be lured out of the castle and made to fight before his son Edward arrived with reinforcements. The Lancastrian army available consisted of 20,000 men while the Yorkist army had only 12,000 men.

John Neville, Baron Neville, who had grown up with Richard as he was the eldest son of Richard’s guardian Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland, arrived at Sandal Castle with 8,000 men but he deserted to the Lancastrians. Even after this, Richard seriously underestimated the size of the Lancastrian army. As December drew to a close, the discipline of the York army was lax. Many York men were allowed to leave the castle precincts to forage for food, signaling to the Lancastrians that there were supply issues. The York scouts were incompetent as they failed to discover the Lancastrians’ plans.

Around Christmas Day, Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of Somerset met with Richard and they agreed that there should be a truce until after the Epiphany (January 6) but the Lancastrians did not intend to keep the truce. For three days, a Lancastrian herald was sent to Richard with orders to provoke him with insults into attacking. On December 29, 1460, the Lancastrians disguised 400 men as Yorkist reinforcements and sent them to join the army at Sandal Castle.

On December 30, 1460, Richard left Sandal Castle. It is not sure why Richard left the safety of the castle. Perhaps a combination of thinking the disguised Lancastrians were Yorkists or planned Richard to lead his men on a foraging expedition. The Yorkists marched towards the Lancastrians located to the north of the castle. As the Yorkists engaged the Lancastrians to their front, others attacked them from the flank and rear, cutting them off from the castle. Richard had no idea that the Lancastrian army was so near or that his army was so outnumbered.

Monument to Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York on the place of his death; Credit – By SMJ, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13540643

Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York was pulled down from his horse and killed. Richard’s second son, 17-year-old Edmund, Earl of Rutland had been fighting with him. Edmund attempted to escape over Wakefield Bridge but was overtaken and killed, possibly by the Lancastrian John Clifford, 9th Baron Clifford to avenge his father’s death at the First Battle of St Albans. After the battle ended some Lancasterian soldiers retrieved Richard’s body, propped it up, and crowned it with a garland of reeds. They then pretended to bow and said, “Hail king without a kingdom!” Lord Clifford ordered the corpses of Richard and his son Edmund to be decapitated and ordered a paper crown to be placed on Richard’s head. The heads of Richard and Edmund were then displayed on pikes over Micklegate Bar, the main entrance of the city of York. The bodies of Richard and Edmund were quietly buried at Pontefract Castle in Pontefract, Yorkshire, England.

Richard’s eldest son King Edward IV of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Richard’s eldest son Edward was now the leader of the Yorkist faction. On February 3, 1461, Edward defeated the Lancastrian army at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross. Edward then took a bold step and declared himself king on March 4, 1461. His decisive victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton on March 29, 1461, cemented his status as King of England. He was crowned at Westminster Abbey on June 29, 1461. However, the former king, Henry VI, still lived and fled to Scotland. There were back and forth reigns of King Edward IV and King Henry VI. Edward IV reigned from 1461 – 1470 and Henry VI reigned from 1470 -1471. The final decisive Yorkist victory was at the Battle of Tewkesbury on May 4, 1471, where Henry VI’s son Edward, Prince of Wales was killed. Henry VI was returned to the Tower of London and died on May 21, 1471, probably murdered on orders from Edward IV. Edward IV reigned until he died in 1483.

Church of St Mary and All Saints, Fotheringhay; Credit – By Theroadislong – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37346663

On July 30, 1476, during the reign of Richard’s son King Edward IV, the remains of Richard and Edmund were reinterred at the Church of Saint Mary and All Saints in Fotheringhay, Northamptonshire, England in a grand ceremony attended by Richard’s sons King Edward IV, George, Duke of Clarence, and Richard, Duke of Gloucester (the future King Richard III) and many noblemen. Thomas Whiting, Chester Herald of Arms in Ordinary, has left a detailed account of the events.

At the entrance to the churchyard, King Edward waited, together with the Duke of Clarence, the Marquis of Dorset, Earl Rivers, Lord Hastings and other noblemen. Upon its arrival the King ‘made obeisance to the body right humbly and put his hand on the body and kissed it, crying all the time.’ The procession moved into the church where two hearses were waiting, one in the choir for the body of the Duke and one in the Lady Chapel for that of the Earl of Rutland, and after the King had retired to his ‘closet’ and the princes and officers of arms had stationed themselves around the hearses, masses were sung and the King’s chamberlain offered for him seven pieces of cloth of gold ‘which were laid in a cross on the body.’ The next day three masses were sung, the Bishop of Lincoln preached a ‘very noble sermon’ and offerings were made by the Duke of Gloucester and other lords, of ‘The Duke of York’s coat of arms, of his shield, his sword, his helmet and his coursers on which rode Lord Ferrers in full armour, holding in his hand an axe reversed.’

When Richard’s wife Cecily Neville, Duchess of York died in 1495, she was interred next to her husband as her will directed. After the choir of the Church of Saint Mary and All Saints was destroyed during the Reformation, Queen Elizabeth I ordered the removal of the smashed York tombs and then created the present York tombs. Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York and his wife Cecily were the great-great-great-grandparents of Queen Elizabeth I.

The tomb of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York and his wife Cecily Neville, to the left of the altar; Credit – Visit to Fotheringhay – Part 3, Exploring the Church of St Mary and All Saints

The Beaufort line eventually did produce a King of England. On August 22, 1485, at the Battle of Bosworth Field, the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the last king of the House of York and the Plantagenet dynasty, King Richard III of England, the youngest son of Richard, 3rd Duke of York, lost his life and his crown. The battle was a decisive victory for the House of Lancaster, whose leader 28-year-old Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, became the first monarch of the House of Tudor as King Henry VII. Henry VII was a great-great-great-grandson of Edward III, King of England through the line of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset, the eldest child of John of Gaunt (son of King Edward III) and his mistress Katherine Swynford who he later married.

The bloodline of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York remains alive among European royalty. His granddaughter Elizabeth of York, the daughter of his son Edward IV, King of England, married King Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch. Through their daughter Margaret Tudor, Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York is an ancestor of the British royal family and many other European royal families.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Church of St Mary and All Saints, Fotheringhay – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_St_Mary_and_All_Saints,_Fotheringhay> [Accessed 1 August 2022].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_of_Conisburgh,_3rd_Earl_of_Cambridge> [Accessed 1 August 2022].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_of_York,_3rd_Duke_of_York> [Accessed 1 August 2022].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2016. King Edward IV of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-edward-iv-of-england/> [Accessed 1 August 2022].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2015. King Henry VI of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-henry-vi-of-england/> [Accessed 1 August 2022].

- Jones, Dan, 2012. The Plantagenets. New York: Viking.

- Weir, Alison, 1995. The Wars of the Roses. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Williamson, David, 1996. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell.